This post appears on the blog of the Campaign for Science and Engineering, as part of a series in the run-up to the UK government’s comprehensive spending review arguing for the value of science spending. As with my earlier pieces, supporting statistics and references can be found in my submission to the BIS select committee productivity inquiry, Innovation, research, and the UK’s productivity crisis (PDF)

Stagnating productivity is one of the biggest problems the UK faces, and it’s the most compelling reason why, despite a tight fiscal climate, the science and innovation budget should be preserved (and ideally, increased).

It’s clear that the government regards deficit reduction as its highest priority, and in pursuit of that, all areas of public spending, including the science budget, are under huge pressure. But the biggest threat to the government’s commitments on deficit reduction may not be the difficulty in achieving departmental spending cuts – it is the possibility that the current slowdown in productivity growth, unprecedented in recent history, continues.

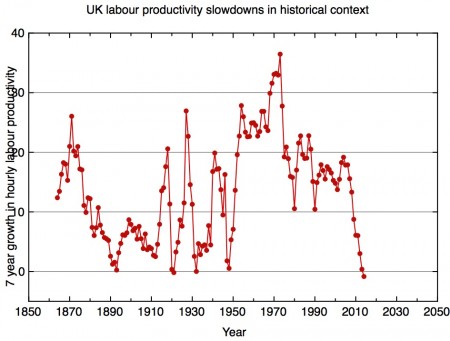

Over many decades, labour productivity in the UK (the amount of GDP produced per hour of labour input) has increased at a steady rate. After the financial crisis in 2008, that steady increase came to an abrupt halt, since when it has flat-lined, and is now at least 15% below the pre-crisis trend. The UK’s productivity performance was already weaker than competitors like the USA, and since the crisis this gap with competitors has opened up yet further. If productivity growth does not improve, the government will miss all its fiscal targets and living standards will continue to stagnate.

Productivity growth, fundamentally, arises from innovation in its broadest sense. The technological innovation that arises from research and development is a part of this, so in searching for the reasons for our weak productivity growth we should look at the UK’s weak R&D investment. This is not the only contributory factor – in recent years, the decline in North Sea oil and a decline in productivity in the financial services sector following the financial crisis provide a headwind that’s not going to go away. This means that we’ll have to boost innovation in other sectors of the economy – like manufacturing and ICT – even more, just to get back to where we were. R&D isn’t the only source of innovation in these and other sectors, but it’s the area in which the UK, compared to its competitors, has been the weakest.

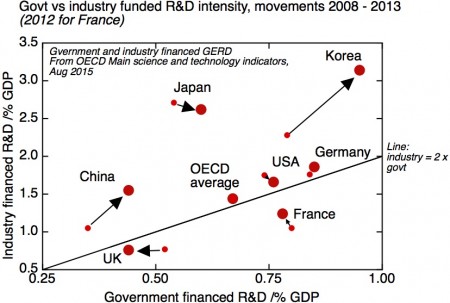

The UK has, for many years, underinvested in R&D – both in the public and the private sectors – compared to traditional competitors like France, Germany and the USA. In recent years, Korea has emerged as the most R&D intensive economy in the world, while China overtook the UK in R&D intensity a few years ago. This is a global race that we’re not merely lagging behind in, we’re running in the wrong direction.

In the short term of an election cycle, it’s probably private sector R&D that has the most direct impact on productivity growth. The UK’s private sector R&D base is not only proportionately smaller than our competitors; more than half of it is done by overseas owned companies – a uniquely high proportion for such a large economy. It is a very positive sign of the perceived strength of the UK’s research base, that overseas companies are so willing to invest in R&D here. But such R&D is footloose.

Much evidence shows that public sector R&D spending “crowds in” substantial further private sector R&D. The other side of that coin is that continuing – or accelerating – the erosion of public investment in R&D that we’ve seen in recent years will lead to a loss of private sector R&D, further undermining our productivity performance. The timescale over which these changes could unfold could be uncomfortably fast.

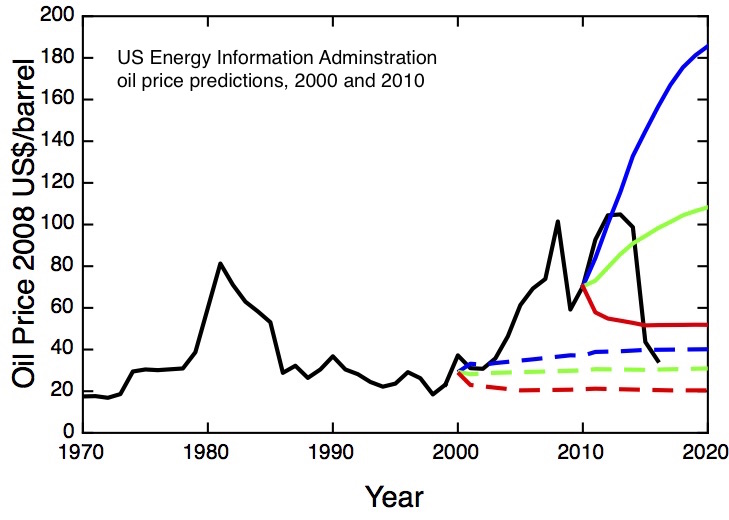

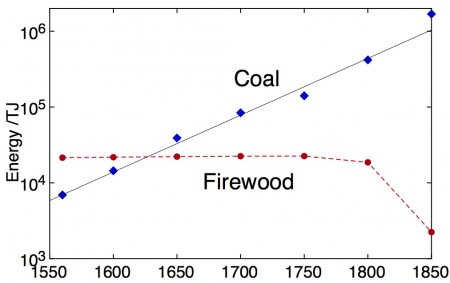

These are the short-term consequences of the neglect of research, but the long-term effects are potentially even more important, and this is something that politicians concerned about their legacy might want to reflect on. The big problems that society faces, and that future governments will have to grapple with – running a health service with a rapidly ageing population, ensuring an affordable supply of sustainable, low carbon energy, to give just two examples – will need all the creativity and ingenuity that science, research and innovation can bring to bear.

The future is unpredictable, so there’ll undoubtedly be new problems to face, and new possibilities to exploit. A strong and diverse science base will give our society the resilience to handle these. So a government that was serious about building the long-term foundations for the continuing health and prosperity of the nation would be careful to ensure the health of the research base that will underpin those necessary innovations.

One way of thinking of our current predicament is that we’re doing an experiment to see what happens if you try to run a large economy at the technology frontier with an R&D intensity about a third smaller than key competitors. The outcome of that experiment seems to be clear. We have seen a slowdown in productivity growth that has persisted far longer than economists and the government expected, and this in turn has led to stagnating living standards and disappointing public finances. Our weak R&D performance isn’t the only cause of these problems, but it is perhaps one of the easiest factors to put right. This is an experiment we should stop now.