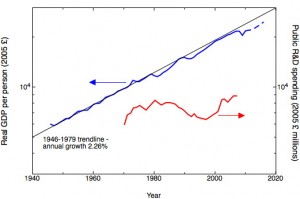

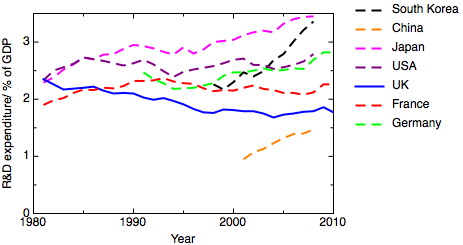

In 1981 the UK was one of the world’s most research and development intensive economies, with large scale R&D efforts being carried out in government and corporate laboratories in many sectors. Over the thirty years between then and now, this situation has dramatically changed. A graph of the R&D intensity of the national economy, measured as the fraction of GDP spent on research and development, shows a long decline through the 1980’s and 1990’s, with some levelling off from 2000 or so. During this period the R&D intensity of other advanced economies, like Japan, Germany, the USA and France, has increased, while in fast developing countries like South Korea and China the growth in R&D intensity has been dramatic. The changes in the UK were in part driven by deliberate government policy, and in part have been the side-effects of the particular model of capitalism that the UK has adopted. Thirty years on, we should be asking what the effects of this have been on our wider economy, and what we should do about it.

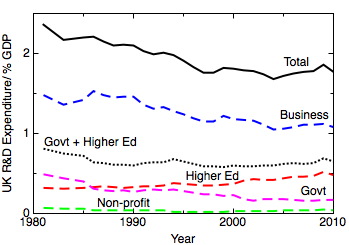

The second graph breaks down where R&D takes place. The largest fractional fall has been in research in government establishments, which has dropped by more than 60%. The largest part of this fall took place in the early part of the period, under a series of Conservative governments. This reflects a general drive towards a smaller state, a run-down of defence research, and the privatisation of major, previously research intensive sectors such as energy. However, it is clear that privatisation didn’t lead to a transfer of the associated R&D to the business sector. It is in the business sector that the largest absolute drop in R&D intensity has taken place – from 1.48% of GDP to 1.08%. Cutting government R&D didn’t lead to increases in private sector R&D, contrary to the expectations of free marketeers who think the state “crowds out” private spending. Instead the business climate of the time, with a drive to unlock “shareholder value” in the short-term, squeezed out longer term investments in R&D. Some seek to explain this drop in R&D intensity in terms of a change in the sectoral balance of the UK economy, away from manufacturing and towards financial services, and this is clearly part of the picture. However, I wonder whether this should be thought of not so much as an explanation, but more as a symptom. I’ve discussed in an earlier post the suggestion that “bad capitalism” – for example, speculations in financial and property markets ,with the downside risk being shouldered by the tax-payer – squeezes out genuine innovation.

The Labour government that came to power in 1997 did worry about the declining R&D intensity of the UK economy, and, in its Science Investment Framework 2004-2014 (PDF), set about trying to reverse the trend. This long-term policy set a target of reaching an overall R&D intensity of 2.5% by 2014, and an increase in R&D intensity in the business sector from to 1.7%. The mechanisms put in place to achieve this included a period of real-terms increase in R&D spending by government, some tax incentives for business R&D, and a new agency for nearer term research in collaboration with business, the Technology Strategy Board. In the event, the increases in government spending on R&D did lead to some increase in the UK’s overall research intensity, but the hoped-for increase in business R&D simply did not happen.

This isn’t predominantly a story about academic science, but it provides a context that’s important to appreciate for some current issues in science policy. Over the last thirty years, the research intensity of the UK’s university sector has increased, from 0.32% of GDP to 0.48% of GDP. This reflects, to some extent, real-term increases in government science budgets, together with the growing success of universities in raising research funds from non UK-government sources. The resulting R&D intensity of the UK HE sector is at the high end of international comparisons (the corresponding figures for Germany, Japan, Korea and the USA are 0.45%, 0.4%, 0.37% and 0.36%). But where the UK is very much an outlier is in the proportion of the country’s research that takes place in universities. This proportion now stands at 26%, which is much higher than international competitors (again, we can compare with Germany, Japan, Korea and the USA, where the proportions are 17%, 12%, 11% and 13%), and much higher now than it has been historically (in 1981 it was 14%). So one way of interpreting the pressure on universities to demonstrate the “impact” of their research, which is such a prominent part of the discourse in UK science policy at the moment, is as a symptom of the disproportionate importance of university research in the overall national R&D picture. But the high proportion of UK R&D carried out in universities is as much a measure of the weakness of the government and corporate applied and strategic research sectors as the strength of its HE research enterprise. The worry, of course, has to be that, given the hollowed-out state of the business and government R&D sectors, where in the past the more applied research needed to convert ideas into new products and services was done, universities won’t be able to meet the expectations being placed on them.

To return to the big picture, I’ve seen surprisingly little discussion of the effects on the UK economy of this dramatic and sustained decrease in research intensity. Aside from the obvious fact that we’re four years into an economic slump with no apparent prospect of rapid recovery, we know that the UK’s productivity growth has been unimpressive, and the lack of new, high tech companies that grow fast to a large scale is frequently commented on – where, people ask, is the UK’s Google? We also know that there are urgent unmet needs that only new innovation can fulfil – in healthcare, in clean energy, for example. Surely now is the time to examine the outcomes of the UK’s thirty year experiment in innovation theory.

Finally, I think it’s worth looking at these statistics again, because they contradict the stories we tell about ourselves as a country. We think of our postwar history as characterised by brilliant invention let down by poor exploitation, whereas the truth is that the UK, in the thirty post-war years, had a substantial and successful applied research and development enterprise. We imagine now that we can make our way in the world as a “knowledge economy”, based on innovation and brain-power. I know that innovation isn’t always the same as research and development, but it seems odd that we should think that innovation can be the speciality of a nation which is substantially less intensive in research and development than its competitors. We should worry instead that we’re in danger of condemning ourselves to being a low innovation, low productivity, low growth economy.