Earlier this year I was asked to write an article explaining nanotechnology and the debates surrounding it for a non-scientific audience with interests in social and policy issues. This article was published in the Summer 2007 issue of the journal Soundings. Here is the unedited version, in installments. Regular readers of the blog will be familiar with most of the arguments already, but I hope they will find it interesting to see it all in one place.

Introduction

Few new technologies have been accompanied by such expansive promises of their potential to change the world as nanotechnology. For some, it will lead to a utopia, in which material want has been abolished and disease is a thing of the past, while others see apocalypse and even the extinction of the human race. Governments and multinationals round the world see nanotechnology as an engine of economic growth, while campaigning groups foresee environmental degradation and a widening of the gap between the rich and poor. But at the heart of these arguments lies a striking lack of consensus about what the technology is or will be, what it will make possible and what its dangers might be. Technologies don’t exist or develop in a vacuum, and nanotechnology is no exception; arguments about the likely, or indeed desirable, trajectory of the technology are as much about their protagonists’ broader aspirations for society as about nanotechnology itself.

Possibilities

Nanotechnology is not a single technology in the way that nuclear technology, agricultural biotechnology, or semiconductor technology are. There is, as yet, no distinctive class of artefacts that can be unambiguously labelled as the product of nanotechnology. It is still, by and large, an activity carried out in laboratories rather than factories, yet the distinctive output of nanotechnology is the production and characterisation of some kind of device, rather than the kind of furthering of fundamental understanding that we would expect from a classical discipline such as physics or chemistry.

What unites the rather disparate group of applied sciences that are referred to as nanotechnologies is simply the length-scale on which they operate. Nanotechnology concerns the creation and manipulation of objects whose size lies somewhere between a nanometer and a few hundred nanometers. To put these numbers in context, it’s worth remembering that as unaided humans, we operate over a range of length-scales that spans a factor of a thousand or so, which we could call the macroscale. Thus the largest objects we can manipulate unaided are about a meter or so in size, while the smallest objects we can manipulate comfortably are about one milimeter. With the aid of light microscopes and tools for micromanipulation, we can also operate on another set of smaller lengthscales, which also spans a factor of a thousand. The upper end of the microscale is thus defined by a millimetre, while the lower end is defined by objects about a micron in size. This is roughly the size of a red blood cell or a typical bacteria, and is about the smallest object that can be easily discerned in a light microscope.

The nanoscale is smaller yet. A micron is one thousand nanometers, and one nanometer is about the size of a medium size molecule. So we can think of the lower limit of the nanoscale as being defined by the size of individual atoms and molecules, while the upper limit is defined by the resolution limits of light microscopes (this limit is somewhat more vague, and one sometimes sees apparently more exact definitions, such as 100 nm, but these in my view are entirely arbitrary).

A number of special features make operating in the nanoscale distinctive. Firstly, there is the question of the tools one needs to see nanoscale structures and to characterise them. Conventional light microscopes cannot resolve structures this small. Electron microscopes can achieve atomic resolution, but they are expensive, difficult to use and prone to artefacts. A new class of techniques – scanning probe microscopies such as scanning tunnelling microscopy and atomic force microscopy – have recently become available which can probe the nanoscale, and the uptake of these relatively cheap and accessible methods has been a big factor in creating the field of nanotechnology.

More fundamentally, the properties of matter themselves often change in interesting and unexpected ways when their dimensions are shrunk to the nanoscale. As a particle becomes smaller, it becomes proportionally more influenced by its surface, which often leads to increases in chemical reactivity. These changes may be highly desirable, yielding, for example, better catalysts for more efficiently effecting chemical transformations, or undesirable, in that they can lead to increased toxicity. Quantum mechanical effects can become important, particularly in the way electrons and light interact, and this can lead to striking and useful effects such as size dependent colour changes. (It’s worth stressing here that while quantum mechanics is counter-intuitive and somewhat mysterious to the uninitiated, it is very well understood and produces definite and quantitative predictions. One sometimes reads that “the laws of physics don’t apply at the nanoscale”. This of course is quite wrong; the laws apply just as they do on any other scale, but sometimes they have different consequences). The continuous restless activity of Brownian motion, that is the manifestation of heat energy at the nanoscale, is dominating. These differences in the way physics works at the nanoscale offer opportunities to achieve new effects, but also means that our intuitions may not always be reliable.

One further feature of the nanoscale is that it is the length scale on which the basic machinery of biology operates. Modern molecular biology and biophysics has revealed a great deal about the sub-cellular apparatus of life, revealing the structure and mode of operation of the astonishingly sophisticated molecular-scale machines that are the basis of all organisms. This is significant in a number of ways. Cell biology provides an existence proof that it is possible to make sophisticated machines on the nanoscale and it provides a model for making such machines. It even provides a toolkit of components that can be isolated from living cells and reassembled in synthetic contexts – this is the enterprise of bionanotechnology. The correspondence of length scales also brings hope that nanotechnology will make it possible to make very specific and targeted interventions into biological systems, leading, it is hoped, to new and powerful methods for medical diagnostics and therapeutics.

Nanotechnology, then, is an eclectic mix of disciplines, including elements of chemistry, physics, materials science, electrical engineering, biology and biotechnology. The way this new discipline has emerged from many existing disciplines is itself very interesting, as it illustrates an evolution of the way science is organised and practised that has occurred largely in response to external events.

The founding myth of nanotechnology places its origin in a lecture given by the American physicist Richard Feynman in 1959, published in 1960 under the title “There’s plenty of room at the bottom”. This didn’t explicitly use the word nanotechnology, but it expressed in visionary and exciting terms the many technical possibilities that would open up if one was able to manipulate matter and make engineering devices on the nanoscale. This lecture is widely invoked by enthusiasts for nanotechnology of all types as laying down the fundamental challenges of the subject, its importance endorsed by the iconic status of Feynman as perhaps the greatest native-born American physicist. However, it seems that the identification of this lecture as a foundational document is retrospective, as there is not much evidence that it made a great deal of impact at the time. Feynman himself did not devote very much further work to these ideas, and the paper was rarely cited until the 1990s.

The word nanotechnology itself was coined by the Japanese scientist Norio Taniguchi in 1974 in the context of ultra-high precision machining. However, the writer who unquestionably propelled the word and the idea into the mainstream was K. Eric Drexler. Drexler wrote a popular and bestselling book “Engines of Creation”, published in 1986, which launched a futuristic and radical vision of a nanotechnology that transformed all aspects of society. In Drexler’s vision, which explicitly invoked Feynman’s lecture, tiny assemblers would be able to take apart and put together any type of matter atom by atom. It would be possible to make any kind of product or artefact from its component atoms at virtually no cost, leading to the end of scarcity, and possibly the end of the money economy. Medicine would be revolutionised; tiny robots would be able to repair the damage caused by illness or injury at the level of individual molecules and individual cells. This could lead to the effective abolition of ageing and death, while a seamless integration of physical and cognitive prostheses would lead to new kinds of enhanced humans. On the downside, free-living, self-replicating assemblers could escape into the wild, outcompete natural life-forms by virtue of their superior materials and design, and transform the earth’s ecosphere into “grey goo”. Thus, in the vision of Drexler, nanotechnology was introduced as a technology of such potential power that it could lead either to the transfiguration of humanity or to its extinction.

There are some interesting and significant themes underlying this radical, “Drexlerite” conception of nanotechnology. One of them is the idea of matter as software. Implicit in Drexler’s worldview is the idea that the nature of all matter can be reduced to a set of coordinates of its constituent atoms. Just as music can be coded in digital form on a CD or MP3 file, and moving images can be reduced to a string of bits, it’s possible to imagine any object, whether an everyday tool, a priceless artwork, or even a natural product, being coded as a string of atomic coordinates. Nanotechnology, in this view, provides an interface between the software world and the physical world; an “assembler” or “nanofactory” generates an object just as a digital printer reproduces an image from its digital, software representation. It is this analogy that seems to make the Drexlerian notion of nanotechnology so attractive to the information technology community.

Predictions of what these “nanofactories” might look like have a very mechanistic feel to them. “Engines of Creation” had little in the way of technical detail supporting it, and included some imagery that felt quite organic and biological. However, following the popular success of “Engines”, Drexler developed his ideas at a more detailed level, publishing another, much more technical book in 1992, called “Nanosystems”. This develops a conception of nanotechnology as mechanical engineering shrunk to atomic dimensions, and it is in this form that the idea of nanotechnology has entered the popular consciousness through science fiction, films and video games. Perhaps the best of all these cultural representations is the science fiction novel “The Diamond Age” by Neal Stephenson, whose conscious evocation of a future shaped by a return to Victorian values rather appropriately mirrors the highly mechanical feel of Drexler’s conception of nanotechnology.

The next major development in nanotechnology was arguably political rather than visionary or scientific. In 2000, President Clinton announced a National Nanotechnology Initiative, with funding of $497 million a year. This initiative survived, and even thrived on, the change of administration in the USA, receiving further support, and funding increases from President Bush. Following this very public initiative from the USA, other governments around the world, and the EU, have similarly announced major funding programs. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this international enthusiasm for nanotechnology at government level is the degree to which it is shared by countries outside those parts of North America, Europe and the Pacific Rim that are traditionally associated with a high intensity of research and development. India, China, Brazil, Iran and South Africa have all designated nanotechnology as a priority area, and in the case of China at least there is some evidence that their performance and output in nanotechnology is beginning to approach or surpass that of some Western countries, including the UK.

Some of the rhetoric associated with the US National Nanotechnology Initiative in its early days was reminiscent of the vision of Drexler – notably, an early document was entitled “Nanotechnology: shaping the world atom by atom”. Perhaps it was useful that such a radical vision for the world changing potential of nanotechnology was present in the background; even if it was not often explicitly invoked, neither did scientists go out of their way to refute it.

This changed in September 2001, when a special issue of the American popular science magazine “Scientific American” contained a number of contributions that were stingingly critical of the Drexler vision of nanotechnology. The most significant of these were by the Harvard nano-chemist George Whitesides, and the Rice University chemist Richard Smalley. Both argued that the Drexler vision of nanoscale machines was simply impossible on technical grounds. Smalley’s contribution was perhaps the most resonant; Smalley had won a Nobel prize for this discovery of a new form of nanoscale carbon, Buckminster fullerene[1], and so his contribution carried significant weight.

The dispute between Smalley and Drexler ran for a while longer, with a published exchange of letters, but its tone became increasingly vituperative. Nonetheless, the result has been that Drexler’s ideas have been largely discredited in both scientific and business circles. The attitude of many scientists is summed up by IBM’s Don Eigler, the first person to demonstrate the controlled manipulation of individual atoms: “To a person, everyone I know who is a practicing scientist thinks of Drexler’s contributions as wrong at best, dangerous at worse. There may be scientists who feel otherwise, I just haven’t run into them.”[2]

Drexler has thus become a very polarising figure. My own view is that this is unfortunate. I believe that Drexler and his followers have greatly underestimated the technical obstacles in the way of his vision of shrunken mechanical engineering. Drexler does deserve credit, though, for pointing out that the remarkable nanoscale machinery of cell biology does provide an existence proof that a sophisticated nanotechnology is possible. However, I think he went on to draw the wrong conclusion from this. Drexler’s position is essentially that we will be able greatly to surpass the capabilities of biological nanotechnology by using rational engineering principles, rather than the vagaries of evolution, to design these machines, and by using stiff and strong materials rather than diamond rather than the soft and floppy proteins and membranes of biology. I believe that this fails to recognise the fact that physics does look very different at the nanoscale, and that the design principles used in biology are optimised by evolution for this different environment[3]. From this, it follows that a radical nanotechnology might well be possible, but that it will look much more like biology than engineering.

Whether or in what form radical nanotechnology does turn out to be possible, much of what is currently on the market described as nanotechnology is very much more incremental in character. Products such as nano-enabled sunscreens, anti-stain fabric coatings, or “anti-ageing” creams certainly do not have anything to do with sophisticated nanoscale machines; instead they feature materials, coatings and structures which have some dimensions controlled on the nanoscale. These are useful and even potentially lucrative products, but they certainly do not represent any discontinuity with previous technology.

Between the mundane current applications of incremental nanotechnology, and the implausible speculations of the futurists, there are areas in which it is realistic to hope for substantial impacts from nanotechnology. Perhaps the biggest impacts will be seen in the three areas of energy, healthcare and information technology. It’s clear that there will be a huge emphasis in the coming years on finding new, more sustainable ways to obtain and transmit energy. Nanotechnology could make many contributions in areas like better batteries and fuel cells, but arguably its biggest impact could be in making solar energy economically viable on a large scale. The problem with conventional solar cells is not efficiency, but cost and manufacturing scalability. Plenty of solar energy lands on the earth, but the total area of conventional solar cells produced a year is orders of magnitude too small to make a significant dent in the world’s total energy budget. New types of solar cell using nanotechnology, and drawing inspiration from the natural process of photosynthesis, are in principle compatible with large area, low cast processing techniques like printing, and it’s not unrealistic to imagine this kind of solar cell being produced in huge plastic sheets at very low cost. In medicine, if the vision of cell-by-cell surgery using nanosubmarines isn’t going to happen, the prospect of the effectiveness of drugs being increased and their side-effects greatly reduced through the use of nanoscale delivery devices is much more realistic. Much more accurate and fast diagnosis of diseases is also in prospect.

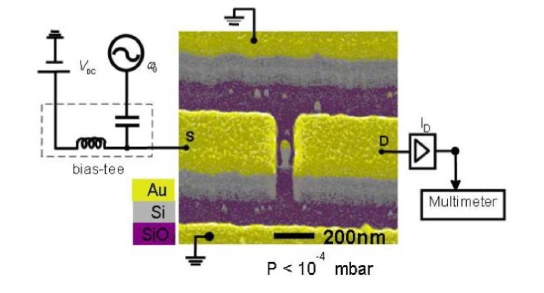

One area in which nanotechnology can already be said to be present in our lives is information technology. The continuous miniaturisation of computing devices has already reached the nanoscale, and this is reflected in the growing impact of information technology on all aspects of the life of most people in the West. It’s interesting that the economic driving force for the continued development of information technologies is no longer computing in its traditional sense, but largely entertainment, through digital music players and digital imaging and video. The continual shrinking of current technologies will probably continue through the dynamic of Moore’s law for ten or fifteen years, allowing at least another hundred-fold increase in computing power. But at this point a number of limits, both physical and economic, are likely to provide serious impediments to further miniaturisation. New nanotechnologies may alter this picture in two ways. It is possible, but by no means certain, that entirely new computing concepts such as quantum computing or molecular electronics may lead to new types of computer of unprecedented power, permitting the further continuation or even acceleration of Moore’s law. On the other hand, developments in plastic electronics may make it possible to make computers that are not especially powerful, but which are very cheap or even disposable. It is this kind of development that is likely to facilitate the idea of “ubiquitous computing” or “the internet of things”, in which it is envisaged that every artefact and product incorporates a computer able to sense its surroundings and to communicate wirelessly with its neighbours. One can see that as a natural, even inevitable, development of technologies like the radio frequency identification devices (RFID) already used as “smart barcodes” by shops like Walmart, but it is clear also that some of the scenarios envisaged could lead to serious concerns about loss of privacy and, potentially, civil liberties.

[1] Nobel Prize for chemistry, 1996, shared with his Rice colleague Robert Curl and the British chemist Sir Harold Kroto, from Sussex University.

[2] Quoted by Chris Toumey in “Reading Feynman Into Nanotech: Does Nanotechnology Descend From Richard Feynman’s 1959 Talk?” (to be published).

[3] This is essentially the argument of my own book “Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and life”, R.A.L. Jones, OUP (2004).

To be continued…