What potential impact of nanotechnology on society should we worry about most? The headlines are being made by the possibility that nanoparticles are especially toxic. This is a real concern, but the problem is relatively bounded and the solutions aren’t difficult to put in place (even if those solutions are going to be bad news for laboratory rats). The primal fear is of loss of control of a technology so powerful that it could lead to the extinction of all life – the problem of grey goo. But as the hubris and lack of realism implicit in the assumption that we will, any time soon, be able to engineer what amounts to a new and superior form of life becomes more apparent, this fear should lose its force.

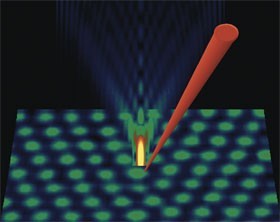

My major worry is in the way we’ll deal with a world in which computing and communication power is so cheap that every object and artefact can have the capability to sense its environment and interact with its neighbours. RFID and smart dust give us a good idea of which way this technology is heading, and developments in evolutionary nanotechnology are sure both to greatly increase the capability and dramatically decrease the cost of such devices.

Worries about the way this is heading are eloquently stated in an interesting new essay on nanotechnology by one of the grandest figures of US academic nanoscience, George Whitesides (the essay is in the current edition of the new Wiley nanotechnology journal, Small, but it probably needs a subscription for full text access).

“In my opinion, the most serious risk of nanotechnology comes, not from hypothetical revolutionary materials or systems, but from the uses of evolutionary nanotechnologies that are already developing rapidly ….

���Universal surveillance������the observation of everyone and everything, in real time, everywhere; a concept suggested by those most concerned with terrorism���is not a technology that I would wish to see cloak a free society, no matter how protectively intended.”