Last Friday I made a visit to HM Treasury, for a round table with the Productivity and Growth Team. My presentation (PDF of the slides here: The UK’s productivity problem – the role of innovation and R&D) covered, very quickly, the ground of my two SPERI papers, The UK’s innovation deficit and how to repair it, and Innovation, research and the UK’s productivity crisis.

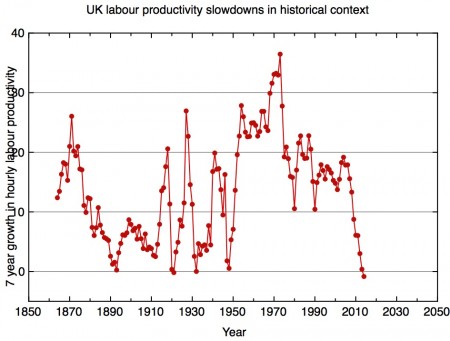

The plot that provoked the most thought-provoking comments was this one, from a recent post, showing the contributions of different sectors to the UK’s productivity growth over the medium term. It’s tempting, on a superficial glance at this plot, to interpret it as saying the UK’s productivity problem is a simple consequence of its manufacturing and ICT sectors having been allowed to shrink too far. I think this conclusion is actually broadly correct; I suspect that the UK economy has suffered from a case of “Dutch disease” in which more productive sectors producing tradable goods have been squeezed out by the resource boom of North Sea oil and a financial services bubble. But I recognise that this conclusion does not follow quite as straightforwardly as one might at first think from this plot alone.

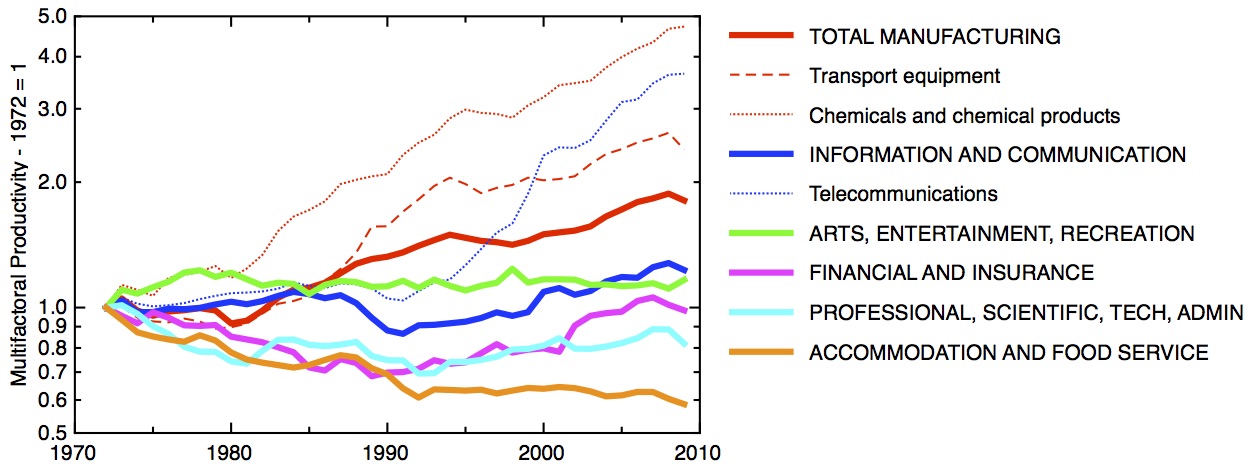

Multifactor productivity growth in selected UK sectors and subsectors since 1972. Data: EU KLEMS database, rebased to 1972=1.

The plot shows multi-factor productivity (aka total factor productivity) for various sectors and subsectors in the UK. Increases in total factor productivity are, in effect, that part of the increase in output that’s not accounted for by extra inputs of labour and capital; this is taken by economists to represent a measure of innovation, in some very general sense.

The central message is clear. In the medium run, over a 40 year period, the manufacturing sector has seen a consistent increase in total factor productivity, while in the service sectors total factor productivity increases have been at best small, and in some cases negative. The case of financial services, which form such a dominant part of the UK economy, is particularly interesting. Although the immediate years leading up to the financial crisis (2001-2008) showed a strong improvement in total factor productivity, which has since fallen back somewhat, over the whole period, since 1972, there has been no net growth in total factor productivity in financial services at all.

We can’t, however, simply conclude from these numbers that manufacturing has been the only driver of overall total factor productivity growth in the UK economy. Firstly, these broad sector classifications conceal a distribution of differently performing sub-sectors. Over this period the two leading sub-sectors are chemicals and telecommunications (the latter a sub-sector of information and communication).

Secondly, there have been significant shifts in the composition of the economy over this period, with the manufacturing sector shrinking in favour of services. My plot only shows rates of productivity growth, and not absolute levels; the overall productivity of the economy could improve if there is a shift from manufacturing to higher value services, even if productivity in those sectors subsequently grows less fast. Thus a shift from manufacturing to financial services could lead to an initial rise in overall productivity followed eventually by slower growth.

Moreover, within each sector and subsector there’s a wide dispersion of productivity performances, not just at sub-sector level, but at the level of individual firms. One interpretation of the rise in manufacturing productivity in the early 1980’s is that this reflects the disappearance of many lower performing firms during that period’s rapid de-industrialisation. On the other hand, a recent OECD report (The Future of Productivity, PDF) highlights what seems to be a global phenomenon since the financial crisis, in which a growing gap has opened up between the highest performing firms, in which productivity has continued to grow, and a long tail of less well performing firms whose productivity has stagnated.

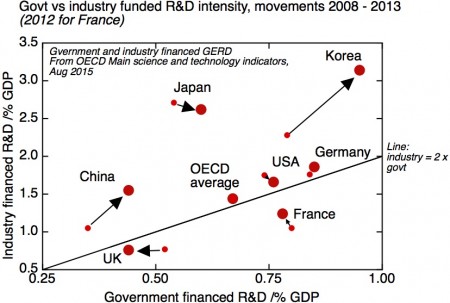

I don’t think there’s any reason to believe that the UK manufacturing sector, though small, is particularly innovative or high performing as a whole. Some relatively old data from Hughes and Mina (PDF) shows that the overall R&D intensity of the UK’s manufacturing sector – expressed as ratio of manufacturing R&D to manufacturing gross value added – was lower than competitor nations and moving in the wrong direction.

This isn’t to say, of course, that there aren’t outstandingly innovative UK manufacturing operations. There clearly are; the issue is whether there are enough of them relative to the overall scale of the UK economy and whether their innovations and practises are diffusing fast enough to the long tail of manufacturing operations that are further from the technological frontier.