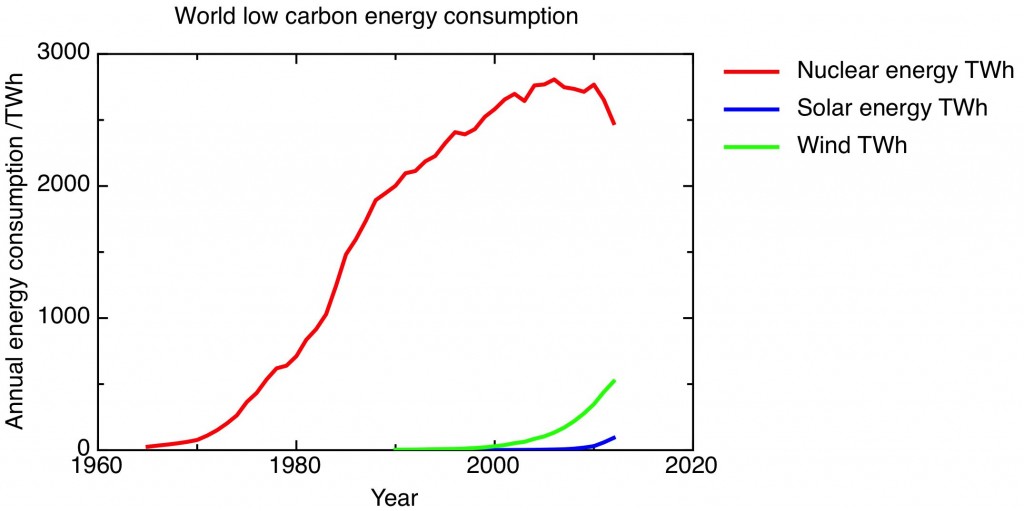

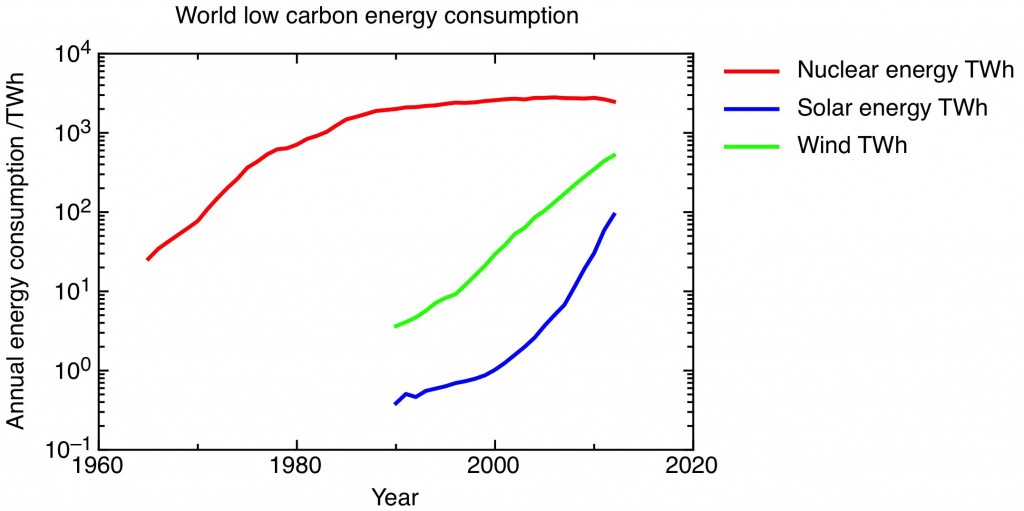

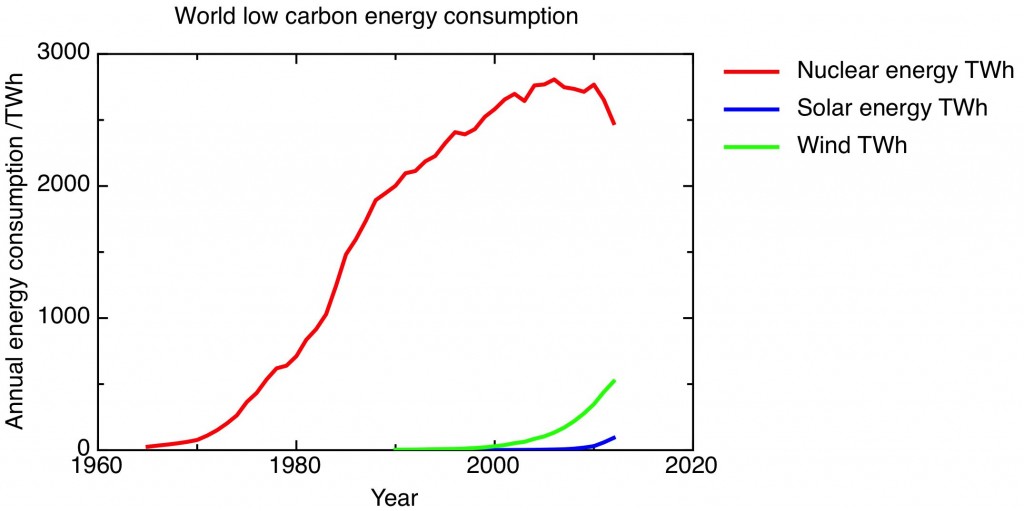

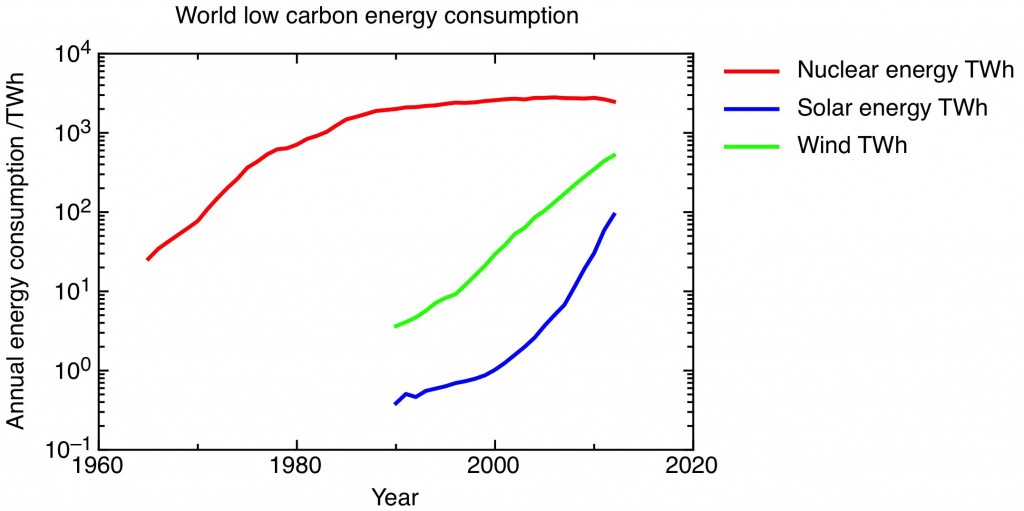

One slightly dispiriting feature of the current environmental movement is the sniping between “old” environmentalists, opposed to nuclear power, and “new” environmentalists who embrace it, about the relative merits of nuclear and solar as low carbon energy sources. Here’s a commentary on that dispute, in the form of a pair of graphs. In fact, it’s two versions of one graph, showing the world consumption of low carbon energy from solar, nuclear and wind over the last forty years or so, the data taken from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013.

The first graph is the case for nuclear. Only nuclear energy makes any dent at all in the world’s total energy consumption (about 22500 TWh of electricity in total was generated in the world in 2012, with more energy consumed directly as oil and gas). Although nuclear generation has dropped off significantly in the last year or two following the Fukushima accident, the experience of the 1970’s and 80’s shows that it is possible to add significant capacity in a reasonable timescale. Nuclear provides the world with a significant amount of low-carbon energy that it’s foolish to imagine can be quickly replaced by renewables.

The second graph is the case for solar. It is the same graph as the first one, but with a logarithmic axis (on this plot constant fractional growth shows up as an increasing straight-line). This shows that world solar energy consumption is increasing at a greater than exponential rate. For the last five years, solar energy consumption has been growing at a rate of 66% a year compounded. (Wind-power is also growing exponentially, but currently at a slower rate than solar). Although in absolute terms, solar energy is only now at the stage that nuclear was in 1971, its growth rate now is much higher than the maximum growth rate for nuclear in the period of its big build out, which was 30% a year compounded in the five years to 1975. And even before Fukushima, the growth in nuclear energy was stagnating, as new nuclear build only just kept up with the decommissioning of the first generation of nuclear plants. Looking at this graph, solar overtaking nuclear by 2020 doesn’t seem an unreasonable extrapolation.

The case for pessimism is made by Roger Pielke, who points out, from the same data set, that the process of decarbonising the world’s energy supply is essentially stagnating, with the proportion of energy consumption from low carbon sources reaching a high point of 13.3% in 1999, from which it has very gently declined.

Of course, looking backwards at historical energy consumption figures can only take us so far in understanding what’s likely to happen next. For that, we need to look at likely future technical developments and at the economic environment. There is a lot of potential for improvement in both these technologies; not enough research and development has been done on any kind of energy technology in the last few years, as I discussed here before – We sold out our energy future.

On the economics, it has to be stressed that the progress we’ve seen with both nuclear and solar has been the result of large-scale state action. In the case of solar, subsidies in Europe have driven installations, while subsidised capital in China has allowed it rapidly to build up a large solar panel manufacturing industry. The nuclear industry has everywhere been closely tied up with the state, with fairly opaque finances.

But one thing sets apart nuclear and solar. The cost of solar power has been steadily falling, with the prospect of grid parity – the moment when solar generated electricity is cheaper than electricity from the grid – imminent in favoured parts of the world, as discussed in a recent FT Analysis article (£). This provides some justification for the subsidies – usually, with any technology, the more you make of something, the cheaper it becomes; solar shows just such a positive learning curve.

For nuclear, on the other hand, the more we install, the costlier it seems to get. Even in France, widely perceived to have been the most effective nuclear building program, with widespread standardisation and big economies of scale, analysis shows that the learning curve is negative, according to this study by Grubler in Energy Policy (£).

What is urgent now is to get the low-carbon fraction of our energy supply growing again. My own view is that this will require new nuclear build, even if only to replace the obsolete plants now being decommissioned. But for nuclear new build to happen at any scale we need to understand and reverse nuclear’s negative learning curve, and learn how to build nuclear plants cheaply and safely. And while the current growth rate of solar is impressive, we need to remember what a low base it is starting from, and continue to innovate, so that the growth rate can continue to the point at which solar is making a significant contribution.