It’s not often that a UK Prime Minister devotes a whole speech to science, so Theresa May’s speech on Monday – PM speech on science and modern Industrial Strategy – was a significant signal by itself. It’s obvious that Brexit consumes a huge amount of political and government bandwidth at the moment, so its interesting that the Prime Minister wants to associate herself with the science and industrial strategy agenda, perhaps to emphasise that Brexit is not completely all-consuming, and there is some space left for domestic policy initiatives.

Beyond the signal, though, I thought there was quite a lot of substance as well. The speech comes at an important moment – the UK government’s science and innovation funding agencies have just been through a major reorganisation, with seven discipline-based research councils, the innovation agency Innovate UK, and a body responsible for the research environment in English universities, coming together in a single organisation, UK Research and Innovation. UKRI began life on 1 April, and it launched its first major strategy document on 14th May. This document isn’t a strategy, though – it’s a “Strategic Prospectus” – a statement of some fundamental principles, together with a commitment to develop a strategy over the months to come. The PM’s speech didn’t mention UKRI at all – somewhat curiously, I thought. Nonetheless, the speech is an important statement of the direction UKRI will be expected to take.

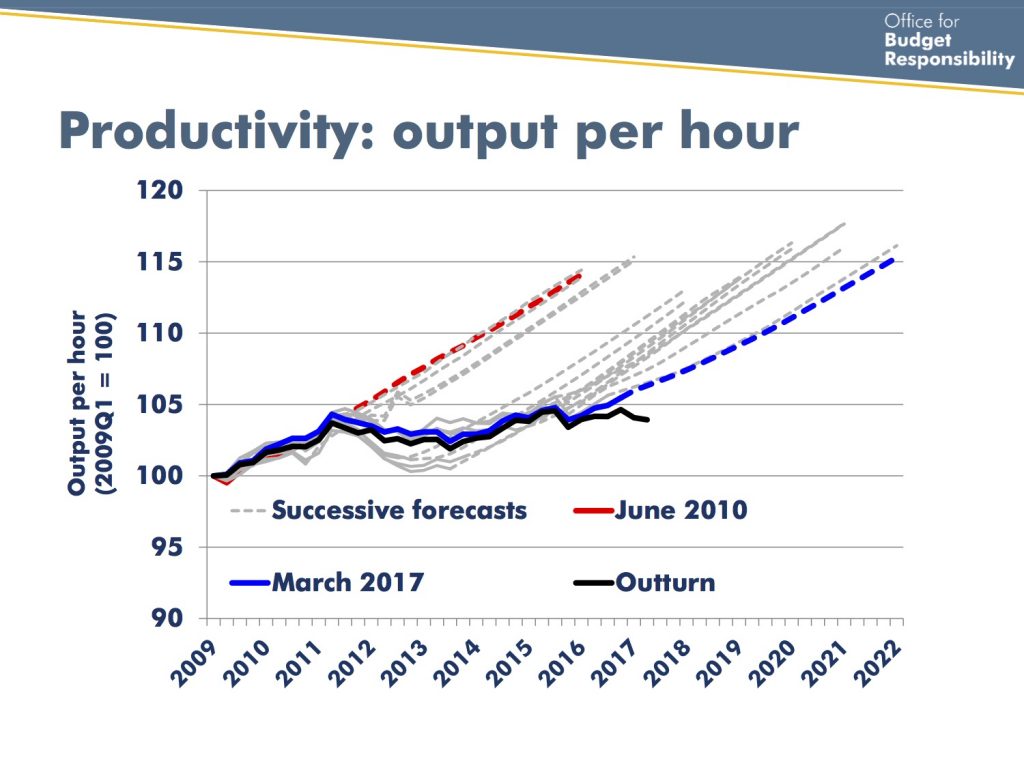

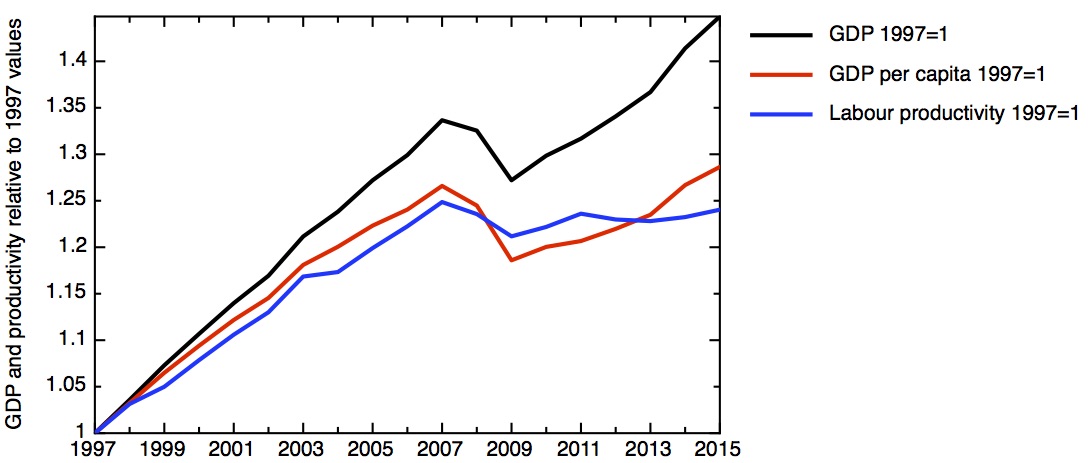

Perhaps the most important commitment was the PM’s stress on the 2.4% R&D intensity target, together with a recognition that this needs a substantial increase in private sector funding, catalysed by state investment. I’ve already written about how stretching this target will be. My estimate is that it will need a £7 billion increase in government spending by 2027 – going well beyond the £2.2 billion increase to 2021 already announced – and a £14 billion increase in private sector spending. These are big numbers; to achieve them will require a significant shifting of the UK’s economic landscape (for the better, I believe). My suspicion is that the attempt to achieve them will have a very big influence on the way UKRI operates, perhaps a bigger influence than people yet realise.

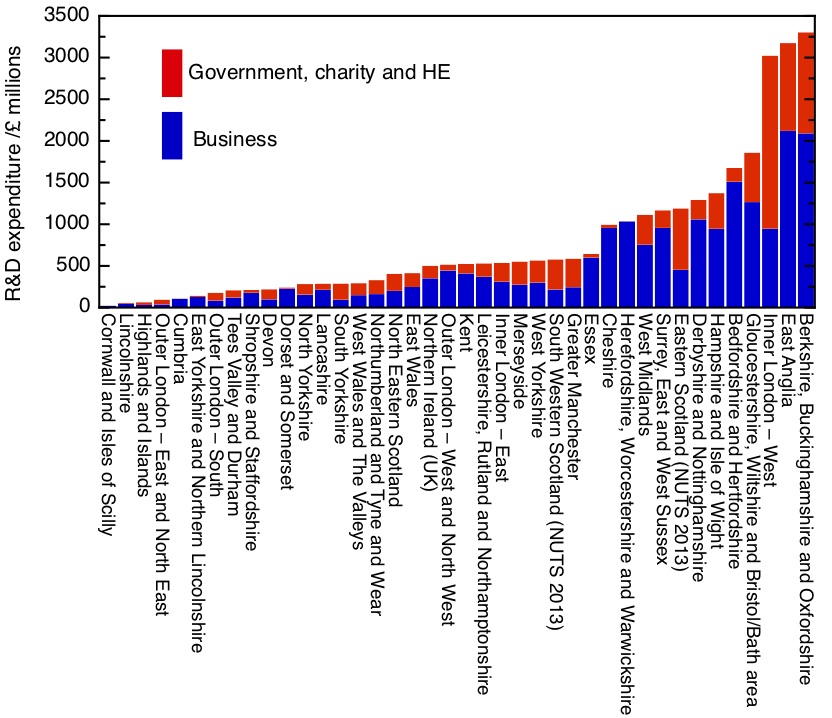

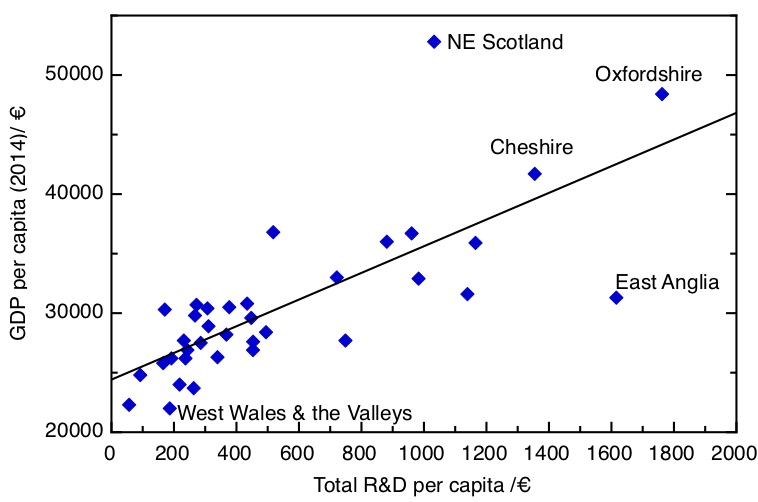

Another important departure from science and innovation policy up to now was the insistence that everywhere in the UK should benefit from it – “backing businesses and building infrastructure not just in London and the South East but across every part of our country”. This needs to include those cities that were pioneers of innovation in the 19th century, but which since have suffered the effects of deindustrialisation. This of course speaks to the profound regional imbalances in R&D expenditure that I highlighted in my recent blogpost Making UKRI work for the whole UK.

Can old cities find new economic tricks? The PM’s speech pointed to some examples – from jute to video games in Dundee, fish to offshore wind in Hull, coal to compound semiconductors in Cardiff. Cities and regions do need to specialise. The PM’s speech didn’t mention any specific mechanisms for encouraging and supporting this, but on the same day UKRI announced a new “place-based” funding competition – the “Strength in Places Fund”, which represents a valuable first step. The aim is to develop interventions on a scale to make a material difference to local and regional economies, and it’s great news that the very distinguished economist Dame Kate Barker – who chaired the Industrial Strategy Commission – has been persuaded to chair the assessment panel.

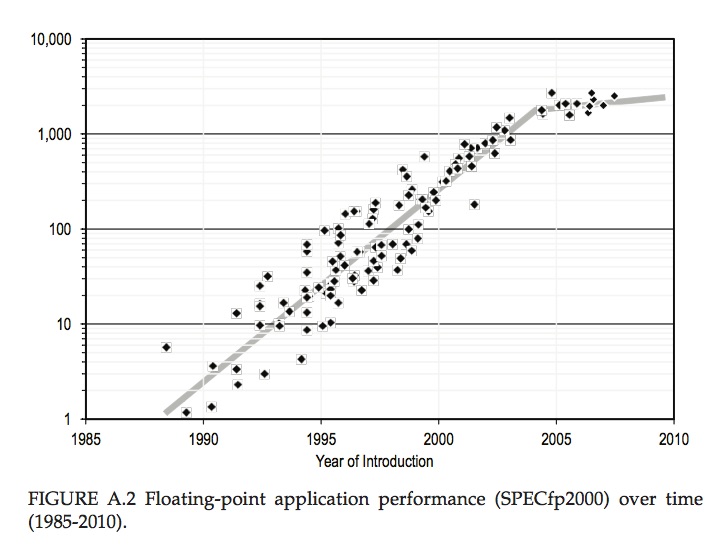

One interesting section of the speech went some way to sharpening up thinking about “Grand Challenges” and “Missions” as organising principles for research. Last November’s Industrial Strategy White Paper introduced four “Grand Challenges” for the UK – on AI and data, the future of mobility, clean growth, and the ageing society. Within these “Grand Challenges”, the intention is to define more specific “missions”. These are more concrete than the Grand Challenges, with some hard targets. Politicians like to announce targets, because they make good headlines – artificial intelligence is “to help prevent 22,000 cancer deaths a year by 2033”, according to the BBC’s (somewhat inaccurate) trail of the speech . I think targets are helpful because they focus policy-makers’ minds on scale. It’s been a besetting sin of UK innovation policy to identify the right things to do, but then to execute them on a scale wholly inadequate to the task.

The PM’s speech announced four such “missions”, and I thought these examples were quite good ones. Two of these missions – around better diagnostics, and support for independent living for older people – are good examples of putting innovation for health and social care at the centre of industrial strategy, as the Industrial Strategy Commission recommended in its final report. Some questions remain.

One simple question that there needs to be an answer for when we talk about “mission-led innovation” is this – who will be the customer for the products that the innovation produces? The government – or the NHS – is the obvious answer for this question in the context of health and social care – but obvious doesn’t mean straightforward. We’ve seen many years of people (including me) saying we should use government procurement much more to drive innovation, to depressingly little effect. What this highlights is that the problems and barriers are as much organisational and cultural as technological. I’m entirely prepared to believe that machine learning techniques could potentially be very helpful in speeding up cancer diagnoses, but realising their benefits will take changes in organisation and working practises.

The other outstanding issue is how these “Grand Challenges” and “missions” are chosen. Is it going to be on the basis of which businessman last caught the ear of a minister, or what a SPAD read in the back of the Economist this week? On the contrary, one would hope – these decisions would be made by aggregating the collective intelligence of a very diverse range of people. This should include scientists, technologists and people from industry, but also the people who see the problems that need to be overcome in their everyday working lives. The UKRI Strategic Prospectus talks warmly about the need for public engagement, including the need to “listen and respond to a diverse range of views and aspirations about what people want research and innovation to do for them”. This needs to be converted into real mechanisms for including these voices in the formulation of these grand challenges and missions.

The Prime Minister may have wanted to give a speech about science to get away from Brexit for a few minutes, but of course there’s no escape, and the consequences of Brexit on our science and innovation system are uncertain and likely to be serious. So it was important and welcome that the PM – particularly this Prime Minister, and former Home Secretary – spelt out the importance of international collaboration, the huge contribution of the many overseas scientists who have chosen to base their careers and lives in the UK, and the value that overseas students bring to our universities. But warm words are not enough, and there needs to be a change in climate and culture in the Home Office on this issue.

One place where we have heard many warm words, but as yet little concrete action, has been in the question of the future relationship between the UK and the EU’s research and innovation programmes. Here it was enormously welcome to hear the Prime Minister state unequivocally that the UK wishes to be fully associated with the successor to Horizon 2020, and is prepared to pay for that. Stating a wish doesn’t make it happen, of course, but it is huge progress to hear that this is now a negotiating goal for the UK government. This is one goal that should be politically unproblematic, and should benefit both sides, so we must hope it can be realised.