How should the hard economic times we’re going through affect the amount of money governments spend on scientific and technological research? The answer depends on your starting point – if you think that science is an optional extra that we do if we’re prosperous, then decreasing prosperity must inevitably mean we can afford to do less science. But if you think that our prosperity depends on the science we do, then if growth is starting to stall, that’s a signal telling you to devote more resources to research. This is a huge oversimplification, of course; the link between science and prosperity can never be automatic. How effective that link will be will depend on the type of science and technology you support, and on the nature of the wider economic system that translates innovations into economic growth. It’s worth taking a look at recent economic history to see some of the issues at play.

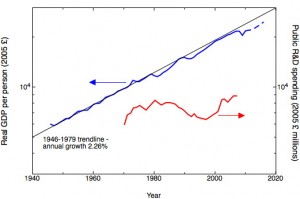

R&D data (red) from the Royal Society Report The Scientific Century adjusted to constant 2005 £s. GDP per person data (blue) from Measuring Worth. Dotted blue line – current projections from the November 2011 forecast of the UK Office of Budgetary Responsibility (uncorrected for population changes).

The graph shows both the real GDP per person in the UK from 1946 up to the present, together with the amount of money, again in real terms, spent by the government on research and development. The GDP graph tells an interesting story in itself, making very clear the discontinuity in economic policy that happened in 1979. In this year Margaret Thatcher’s new Conservative government overthrew a thirty year broad consensus, shared by both parties, on how the economy should be managed. Before 1979, we had a mixed economy, with substantial industrial sectors under state control, highly regulated financial markets, including controls on the flow of capital in and out of the country, and the macro-economy governed by the principles of Keynesian demand management. After 1979, it was not Keynes, but Hayek, who supplied the intellectual underpinning, and we saw progressive privatisation of those parts of the economy under state control, the abolition of controls on capital movements and deregulation of financial markets. In terms of economic growth, measured in real GDP per person, the period between 1946 and 1979 was remarkable, with a steady increase of 2.26% per year – this is, I think, the longest sustained period of high growth in the modern era. Since 1979, we’ve seen a succession of deep recessions, followed by periods of rapid, and evidently unsustainable growth, sustained by asset price bubbles. The peaks of these periods of growth have barely attained the pre-1979 trend line, while in our current economic travails we find ourselves about 9% below trend. Not only does there seem no imminent prospect of the rapid growth we’d need to return to that trend line, but there now seems to be a likelihood of another recession.

The plot for public R&D spending tells its own story, which also shows a turning point with the Thatcher government. From 1980 until 1998, we see a substantial long-term decline in research spending, not just as a fraction of GDP, but in absolute terms; since 1998 research spending has increased again in real terms, though not substantially faster than the rise in GDP over the same period. Underlying the decline were a number of factors. There was a real squeeze on spending in research in Universities, well remembered by those who were working in them at the time. Meanwhile the research spending in those industries that were being privatised – such as telecommunications and energy – was removed from the government spending figures. And the activities of government research laboratories – particularly those associated with defense and the nuclear industry – were significantly wound down. Underlying this winding down of research was both a political motive and an ideological one. Big government spending on high technology was associated with the corporate politics of the 1960’s, subscribed to by both parties but particularly associated with Labour, and the memorable slogan “The White Heat of Technology”. To its detractors this summoned up associations with projects like the supersonic passenger aircraft Concord, a technological triumph but a commercial disaster. To the adherents of the Hayekian free market ideology that underpinned the Thatcher government, the state had no business doing any research but the most basic and far from market. In fact, state-supported research was likely to be not only less efficient and less effectively directed than research in the private sector, but by “squeezing out” such private sector research it would actually make the economy less efficient.

The idea that state support of research reduces support of research by the private sector by “squeezing out” remains attractive to free market ideologues, but the empirical evidence points to the opposite conclusion – state spending and private sector spending on research support each other, with increases in state R&D spending leading to increases in R&D by business (see for example Falk M (2006). What drives business research and development intensity across OECD countries? (PDF), Applied Economics 38 p 533). Certainly, in the UK, the near-halving of government R&D spend between 1980 and 1999 did not lead to an increase in R&D by business; instead, this also fell from about 1.4% of GDP to 1.2%. Not only did those companies that had been privatised substantially reduce their R&D spending, but other major players in industrial R&D – such as the chemical company ICI and the electronics company GEC – substantially cut back their activities. At the time many rationalised this as the inevitable result of the UK economy changing its mix of sectors, away from manufacturing towards service sectors such as the financial service industry.

None of this answers the questions: how much should one spend on R&D, and what difference do changes in R&D spend make to economic performance? It is certainly clear that the decline in R&D spending in the UK isn’t correlated with any improvement in its economic performance. International comparisons show that the proportion of GDP spent on R&D in the UK is significantly lower than most of its major competitors, and within this the proportion of R&D supported by business is itself unusually low . On the other hand, the performance of the UK science base, as measured by academic measures rather than economic ones, is strikingly good. Updating a much-quoted formula, the UK accounts for 3% of the total world R&D spend, it has 4.3% of the world’s researchers, who produce 6.4% of the world’s scientific articles, which attract 10.9% of the world’s citations and produce 13.8% of the world’s top 1% of highly cited papers (these figures come from the analysis in the recent report The International Comparative Performance of the UK Research Base).

This formula is usually quoted to argue for the productivity and effectiveness of the UK research base, and it clearly tells a powerful story about its strength as measured in purely academic terms. But does this mean we get the best out of our research in economic terms? The partial recovery in government R&D spending that we saw from 1998 until last year brought real terms increases in science budgets (though without significantly increasing the fraction of GDP spent on science). These increases were focused on basic research, whose importance as a proportion of total government science spending doubled between 1986 and 2005. This has allowed us to preserve the strength of our academic research base, but the decline in more applied R&D in both government and industrial laboratories has weakened our capacity to convert this strength into economic growth.

Our national economic experiment in deregulated capitalism ended in failure, as the 2008 banking collapse and subsequent economic slump has made clear. I don’t know how much the systematic running down of our national research and development capability in the 1980’s and 1990’s contributed to this failure, but I suspect that it’s a significant part of the bigger picture of misallocation of resources associated with the booms and the busts, and the associated disappointingly slow growth in economic productivity.

What should we do now? Everyone talks about the need to “rebalance the economy”, and the government has just released an “Innovation and Research Strategy for Growth”, which claims that “The Government is putting innovation and research at the heart of its growth agenda”. The contents of this strategy – in truth largely a compendium of small-scale interventions that have already been announced, which together still don’t fully reverse last year’s cuts in research capital spending – are of a scale that doesn’t begin to meet this challenge. What we should have seen is, not just a commitment to maintain the strength of the fundamental science base, important though that is, but a real will to reverse the national decline in applied research.

Dear Richard,

do you think that research scientists in industrial companies have been involved in the senior management enough or prized by the senior management ? Is it a case that accountants have not fully appreciated these people ?

Shortsightedness has left a lot of companies with lacklustre product pipelines, for instance BIg Pharma is facing a drought of new lucrative drugs. Also the recent crisis at Olympus shows that some companies have been more interested in playing the markets than developing blockbusting technology that will deliver profits and maintain their edge over competitors.

Andy Parnell

I think it’s very difficult to tie GDP into anything convincingly because there’s so many factors that affect it.

Still if there was data from many many countries on public research spending and gdp, perhaps a more convincing case could be put forward?

Andy, short-termism in one sense is clearly the problem, but I think it’s too simplistic to blame this on having too many accountants or not enough scientists in management – people making investment decisions respond to what’s rational in the circumstances they are in, and it is this broader environment that makes it difficult to justify long-term investments (this really is what I was arguing in my earlier post on good capitalism and bad capitalism).

Chris, I agree that it is difficult to make a direct link between public research spending and GDP, and there’s a disclaimer to this effect in my penultimate paragraph. The point I was making, though, was that the reduction in R&D expenditure in the UK didn’t happen by accident, it was an integral part of a broader ideological approach to economic policy which, the GDP evidence suggests, has failed.

Yes, that’s fair enough, to an extent. But politics isn’t a curate’s egg. Perhaps reducing R&D expenditure was the one right thing the governments in question did, and everything else they did wrong. I’m not suggesting that seriously, but proving it one way or another is nigh on impossible with a sample of one and so many variables and time delay effects.

That said, a proper report on research funding and growth could be a real boost for science worldwide. I’m sure there is data from most advanced countries that could be obtained, and its not like you RS guys would have a shortage of international colleagues willing to help out. Get some statisticians on the numbers then go into every meeting on the matter with a giant pile of evidence to back you up. I can already hear the jeers of ‘vested interest’ from the back benches.

Chris, there is quite a lot of that kind of econometric study out there already. There’s a good review in this paper from Ben Martin at SPRU The benefits of publically funded research (PDF).

What if the government gave funding to private companies, with the agreement that these companies in turn fund what they believe to be economically profitable academic research within universities etc? I don’t know if schemes like these already exist but they could be a compromise between free-market and state controlled ideologies.

Warren – it’s certainly the case that the US government funds a great deal of research in the private sector (usually in defense) and some of that filters back to universities and national labs. UK funding from the Technology Strategy Board – where the TSB funds consortia of companies and universities, generally company-led, has some similarities, though its on a much smaller scale and closer to application than the US situation. Some EU framework projects also look a bit like this.

Indexing public R+D inversely to GDP isn’t bad. Better is median GDP. Better is estimating future debt service costs and subtracting from GDP as debt kills public R+D public support. Because public R+D generally takes longer to recoup products, it needs a longer funding timeline (that can be killed if disappointing early R+D). This also means there is a time penalty and the public R+D funding should be less than private, all else equal (can tax private R+D for more public R+D).

R+D could be indexed inversely to the person-yrs of research, lead researchers have. But is international R+D system now; could buy foreign researchers. Can be indexed inversely to R+D lab equipment depreciation.

Demographics may play a role as want to maximize number of products introduced before retirement; Japan’s demographics would suggest nearer term R+D so can pay for public budget, but not so for China.

There are abstractions that get more bang for buck. “Directions for future research” is often a part of papers. But the scientist keeps his/her own best ideas to achieve future salary. There is something to be gained by focussing on specialty, but a better pyramid could be built if the scientist or research group were given compensation for outputting publicly accessible non-WMD future research paper ideas. Instead of following a path throughout one’s career, another scientist would take the next step. The original scientist would switch to working on the third idea or something tangential that has just emerged. You guys did this for Ideas Factory. Maybe time for some teleconferencing science; surely if holograms.