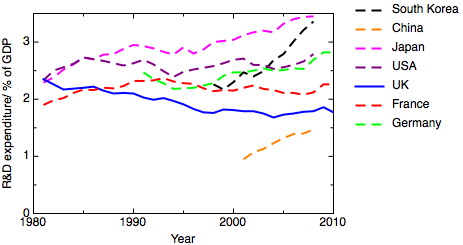

In 1981 the UK was one of the world’s most research and development intensive economies, with large scale R&D efforts being carried out in government and corporate laboratories in many sectors. Over the thirty years between then and now, this situation has dramatically changed. A graph of the R&D intensity of the national economy, measured as the fraction of GDP spent on research and development, shows a long decline through the 1980’s and 1990’s, with some levelling off from 2000 or so. During this period the R&D intensity of other advanced economies, like Japan, Germany, the USA and France, has increased, while in fast developing countries like South Korea and China the growth in R&D intensity has been dramatic. The changes in the UK were in part driven by deliberate government policy, and in part have been the side-effects of the particular model of capitalism that the UK has adopted. Thirty years on, we should be asking what the effects of this have been on our wider economy, and what we should do about it.

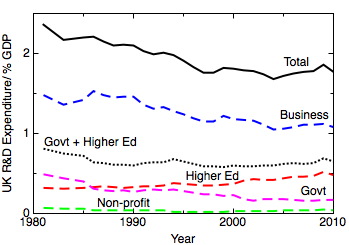

The second graph breaks down where R&D takes place. The largest fractional fall has been in research in government establishments, which has dropped by more than 60%. The largest part of this fall took place in the early part of the period, under a series of Conservative governments. This reflects a general drive towards a smaller state, a run-down of defence research, and the privatisation of major, previously research intensive sectors such as energy. However, it is clear that privatisation didn’t lead to a transfer of the associated R&D to the business sector. It is in the business sector that the largest absolute drop in R&D intensity has taken place – from 1.48% of GDP to 1.08%. Cutting government R&D didn’t lead to increases in private sector R&D, contrary to the expectations of free marketeers who think the state “crowds out” private spending. Instead the business climate of the time, with a drive to unlock “shareholder value” in the short-term, squeezed out longer term investments in R&D. Some seek to explain this drop in R&D intensity in terms of a change in the sectoral balance of the UK economy, away from manufacturing and towards financial services, and this is clearly part of the picture. However, I wonder whether this should be thought of not so much as an explanation, but more as a symptom. I’ve discussed in an earlier post the suggestion that “bad capitalism” – for example, speculations in financial and property markets ,with the downside risk being shouldered by the tax-payer – squeezes out genuine innovation.

The Labour government that came to power in 1997 did worry about the declining R&D intensity of the UK economy, and, in its Science Investment Framework 2004-2014 (PDF), set about trying to reverse the trend. This long-term policy set a target of reaching an overall R&D intensity of 2.5% by 2014, and an increase in R&D intensity in the business sector from to 1.7%. The mechanisms put in place to achieve this included a period of real-terms increase in R&D spending by government, some tax incentives for business R&D, and a new agency for nearer term research in collaboration with business, the Technology Strategy Board. In the event, the increases in government spending on R&D did lead to some increase in the UK’s overall research intensity, but the hoped-for increase in business R&D simply did not happen.

This isn’t predominantly a story about academic science, but it provides a context that’s important to appreciate for some current issues in science policy. Over the last thirty years, the research intensity of the UK’s university sector has increased, from 0.32% of GDP to 0.48% of GDP. This reflects, to some extent, real-term increases in government science budgets, together with the growing success of universities in raising research funds from non UK-government sources. The resulting R&D intensity of the UK HE sector is at the high end of international comparisons (the corresponding figures for Germany, Japan, Korea and the USA are 0.45%, 0.4%, 0.37% and 0.36%). But where the UK is very much an outlier is in the proportion of the country’s research that takes place in universities. This proportion now stands at 26%, which is much higher than international competitors (again, we can compare with Germany, Japan, Korea and the USA, where the proportions are 17%, 12%, 11% and 13%), and much higher now than it has been historically (in 1981 it was 14%). So one way of interpreting the pressure on universities to demonstrate the “impact” of their research, which is such a prominent part of the discourse in UK science policy at the moment, is as a symptom of the disproportionate importance of university research in the overall national R&D picture. But the high proportion of UK R&D carried out in universities is as much a measure of the weakness of the government and corporate applied and strategic research sectors as the strength of its HE research enterprise. The worry, of course, has to be that, given the hollowed-out state of the business and government R&D sectors, where in the past the more applied research needed to convert ideas into new products and services was done, universities won’t be able to meet the expectations being placed on them.

To return to the big picture, I’ve seen surprisingly little discussion of the effects on the UK economy of this dramatic and sustained decrease in research intensity. Aside from the obvious fact that we’re four years into an economic slump with no apparent prospect of rapid recovery, we know that the UK’s productivity growth has been unimpressive, and the lack of new, high tech companies that grow fast to a large scale is frequently commented on – where, people ask, is the UK’s Google? We also know that there are urgent unmet needs that only new innovation can fulfil – in healthcare, in clean energy, for example. Surely now is the time to examine the outcomes of the UK’s thirty year experiment in innovation theory.

Finally, I think it’s worth looking at these statistics again, because they contradict the stories we tell about ourselves as a country. We think of our postwar history as characterised by brilliant invention let down by poor exploitation, whereas the truth is that the UK, in the thirty post-war years, had a substantial and successful applied research and development enterprise. We imagine now that we can make our way in the world as a “knowledge economy”, based on innovation and brain-power. I know that innovation isn’t always the same as research and development, but it seems odd that we should think that innovation can be the speciality of a nation which is substantially less intensive in research and development than its competitors. We should worry instead that we’re in danger of condemning ourselves to being a low innovation, low productivity, low growth economy.

The obsession with universities as the drivers of growth in this country is problematic. For one, it gives our graduates in science subjects few careers options outside of Universities or University science parks if they really want to stay in research. The reason I suspect is that universities can be cajoled into doing what the government wants in a way that the business sector cannot. This government, like its predecessor, needs to consider its targets carefully. For example, if the government decided that one metric it would like to improve is the number of people employed in corporate research labs (and thus the number of such labs), how would it go about this? As you say, the closure of government-funded labs has not been compensated by an increase in research funded by business in the country. (I have no great problem with the closure of such state-funded facilities, which had the potential for national hubris. Does anybody remember the advanced passenger train of the late 1970s?)

One problem with current policy is that most of the growth seems to come from Universities. Start-ups that are worth anything then get bought by bigger and hungrier competitors, which may mean that the expertise leaves the country.

Another possible problem is that our young entrepreneurs may be more risk averse than those in America, for example. This means that when the bigger fish come hunting they sell rather than hold out for bigger things. This may be why the UK google does not arrive. Having said that, how often does a google arrive anyway? Looking for such rare events as a determining factor in a country’s success is pretty daft.

My view is that the government ought to think about what it really means by improving our ability to make things. This means that it ought to base its industrial policy on increasing corporate research rather than micromanaging “impact” and such like.

The issue, I suggest, is not just one of R&D intensity, but also the effective exploitation of the R&D. Until recently, universities have not usually seen the importance of this, probably because there is no direct reward for this activity. Any exploitation would either occur through technology transfer with large companies, or by the universities setting up incubation units for their academics / students, but there was very little technology transfer into the SME sector. If we are going to rely heavily on our universities for R&D, and in the short term, that is likely, this process needs substantial improvement.

Mark, I do remember the APT. As I remember, the technology was disposed of to the Italians, who sold it back to us in the form of those Pendolino trains that make me travel sick on the rare occasions that I get to travel from London to the North West. Should we worry about having a very weak government R&D sector? It’s worth asking two questions – how’s our economy doing compared to other countries with stronger government R&D? The numbers in question are (all figures for R&D in government sector as % of GDP) UK .16%, Germany .38%, USA .30%, China .27%, Japan .29%, South Korea .41%. And how’s our economy doing now compared to the time when we also had a strong government R&D sector?

Martin, I think you underestimate the efforts universities are making in exploitation of R&D beyond spin-outs, which are in truth a small part of the overall picture. You can get a measure of this from the HE-BCI survey (latest figures here). The biggest activity is contract research (£983 million), collaborative research (£749 million) and consultancy (£362 million) – income from IP only amounts to £84 million. To give you a sense of what we do at Sheffield, take a look at our Advanced Manufacturing Institute.

This is a fantastic post Richard and I hope it is widely disseminated. I agree with Mark.

The focus on University R&D and spin-out or licensing is misguided and is not a good alternative to a healthy legacy industrial base. All R&D should at some level be supportive of an industrial base. Once that declines what is the reason d’être for R&D? That’s the disconnect. We have a well organised and strong science lobby and they have the ear of Govt to some degree. The University spend has held up pretty well under their influence although not as big as other countries in the belief that from R&D good things will flow such as innovation. Flawed thinking. What has been missed is the steady decline in industrial R&D, which is a symptom of our deindustrialisation. You often here politicians espousing the need for UK industry to spend more on R&D. Makes me laugh out loud …what industry? UK Universities need to worry less about exploitation if IP via spin-outs or licensing and look more closely at basic technology transfer to UK industry.

The UK Govt. needs to redirect resources to UK industry to get industrial innovation going. We have enough University IP washing around in the UK to service two or three industrial revolutions! How do I know this? Because we are giving IP away constantly through our lack of an appropriate innovation ecosystem to overseas based companies. Graphene is the example of the moment. £50 million pushed into a non-existent ecosystem around Manchester, when the UK is already a third rate player in graphene innovation is simply logic gone mad. Recent publicity was talking up the possibility of Manchester being the Graphene Valley akin to Silicon Valley. Delusional hubris. Of the 45 companies signing up for this that vast majority will not be creating jobs in the UK; it is in effect an investment in technology transfer out of the UK. We missed that boat on graphene lets learn from our mistakes and catch the next one.

Richard,

The point is that again Govt. R&D is vanity. The R&D has to go somewhere to be useful. The history shows us that Govt. R&D in the UK was very poorly transferred into the industrial base. It was almost as if never the twain shall meet. When they did meet the costs to industry in having to carry inefficient Govt R&D support was usually catastrophic to the success of the project. Quality not quantity is the key.

On the contract/collaborative and consultancy research I would not be too surprised if most of that money is in fact money from outside of the UK and not from the UK industrial base.

Income from IP at £84 million is probably less than the R&D costs and acquisition costs of the IP and so commercially irrelevant.

Incidentally UK Universities in contrast to German and US Universities in their own countries are this country’s most prolific filers of patents, because there is much lower industrial patent activity because there is no industry.

A few years ago The Economist had a fantastic infographic (Hans Rosling style) which looked at R&D spend from the early 1980s for many countries and also had per capita, per GDP and IP activity comparisons. It was a startling infographic. Whichever way you manipulated the axis or data the UK was either static or going backwards. Pity it’s not available on The Economist website anymore, you would have had a lot of fun with it.

The phrase “the stories we tell about ourselves as a country” encompasses the role of the media in all this. Finance journalists have always garnered more page space than those writing about making stuff. This feeds into those stories.

There are “secret” caches of excellence that the media usually ignore. The Economist, for example, in its latest issue, points out that GKN has been quietly doing things with little recognition.

Then again, the technology sector – from which I exclude IT, much of which has only tenuous links with technology – does very little to blow its trumpet. Had it been better at PR, Mrs Thatcher might not have found it so easy to write off the sector in favour of the “service” economy. And the Labour government might have been quicker to rediscover manufacturing.

Her sell off of many nationalised industries also called a halt to much of the R&D that they carried out. While this was never a reason for maintaining public ownership of the likes of BT, which, as the “ministry of communications”, tried to call too many technology shots, jettisoning the whole caboodle led to a dramatic decline in the UK’s industrial R&D, throwing the burden on academics who, for far too long, never really saw the point of doing things that might be “useful”.

That has changed, but only after two decades of decline.

Further to Nick’s points above, I should suggest that the government is hindering industrial research and development when it thinks it is helping it.

One needs to consider the effect on industry itself of the way that the government encourages industrial collaboration with academia. If the government creates a scheme with which industry partners a university, then there is a net transfer of capacity to the university. If the government is paying the University to do work with industry that could and perhaps should have been done by industry then industry does not need that expertise in house, so it can cut back to save money. When the point comes that the research needs to be confidential, industry has retrenched so much that its further development of the technology is sent to its corporate research labs overseas.

So when Nick writes “history shows us that Govt. R&D in the UK was very poorly transferred into the industrial base,” I’d take it even further. I’d suggest R&D is being transferred from the industrial base into universities. Of course, all governments have schemes to help bring academia and university together, but the UK probably takes it a little too far.

I know my argument is simplistic, but it is not overly simplistic. Government support for industry should be directed at industry, and not at universities. This does not mean that universities should be neglected. It is of the essence that universities are absolutely top class because there is no knowledge economy that does not have a world class university sector.

Nick, I agree with you that government R&D needs to be connected to the industrial base, but I don’t think it follows that it is necessarily vanity. I’d be enormously surprised if the 0.41% of GDP spent by South Korea in its government labs isn’t pretty directly tied to the priorites of Samsung and LG; if you visit a lab like ITRI in Taiwan it’s clearly deeply tied in to its local manufacturing enterprises, and the German Fraunhofer Institutes, with their funding pattern of 1/3 direct industrial funding, 1/3 collaborative research, 1/3 state core funding, are widely held up as a model for engaging industry. I appreciate that this offends Mark’s view that industry should be doing this stuff by themselves, but countries like Germany and Korea suffer the great disadvantage that their leaders never read any Hayek, and they’re condemned as a result to having robust and growing economies with strong manufacturing sectors. But there is an important point from Mark’s comment about the capacity of industry to absorb and exploit the results of R&D.

Throughout most of the nineties I was the director of technology programmes for an organisation called the Marine Technology Directorate. MTD morphed into the Centre for Marine and Petroluem Technology and then became the Industry Technology Facilitator.

MTD had control over around £5m worth of Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council annual funding which we used to lever in industrial funding from oil/gas companies including supply side companies. We regularly spent between £10m to £15m per annum on R&D programmes that often included multiple universities and more often than not a number of companies especially SMEs.

The owners of MTD were it’s member companies and their main aim was to ensure that as much R&D as possible was properly commercialised either through knowledge transfer, licencing to a project’s industrial participant or via a spin-out. All participants in a project had the automatic right to a licence on request with royalties to be paid back to the projects supporters (inc the universities) as the technology began to earn real income.

It was a mechanism that worked like a dream. The researchers liked it and most importantly industry did as well and it was happy to fund both the organisation and a range of programmes.

However – EPSRC hated it because they had little control over it and when Labour came back into govt in 97 it was agreed by them that we should no longer get that £5m worth of funding. Inevitably then industry also slowly withdrew and the whole thing collapsed. What exists now is a simple facilitator that tries to pull together projects but has no funding behind it. As a consequence the amount of R&D going on in the sector has now fallen back badly.

That said it is also recognised that despite nearly 40 yrs of oil and gas the UK’s energy related industrial base is pathetically small and the former energy minister Malcolm Wicks said in his report on Energy Security that the UK’s poor R&D performance (compared to our competitors) was linked to this.

Richard,

What I mean by “vanity” is the numbers game. It’s not how much you spend it is how you spend it. You are right about Korea and Germany; it is how they spent the money not the amount that makes the big difference. They also put much less faith in the primacy of University Research; it has its place.

Dick,

That is a very illustrative anecdote. Labour for largely ideological and political reasons felt more comfortable with University funding directly and indirectly and with expansion of the student base than with continuing to support industrialists.

I think it is really worth developing the theme “poor R&D performance”. The perception in the UK is that it is all about budgets and the amount of money. Nothing could be further from the truth. If you look at other metrics such as “innovation”, growth levels in manufacturing and generally STEM industries, long term employment prospects for STEM graduates in the UK and the patent statistics you see a very large disconnect. If you could look at a combination of these metrics what you see is that in relative terms R&D has not been hit that badly hit over the past 30 years at least in Universities but for some reason the investment of 3-4 decades in R&D has not been transformed into significant sustainable value for the UK economy. Over the same period Japan, US, Germany and France have made much better use of their investments in R&D and our investments! Plenty of UK Nobel Prize science is now supporting major industries outside of the UK. I have a problem with the focus of the politicians on the University sector. If we had status quo and the R&D mattered we would not have seen a massive contraction in the UK industrial base and what I see in patent stats. Not the fault of Universities, not the fault of focus on wrong R&D IMHO, just a disconnect. R&D is not an end in itself it has to go somewhere; if there is nowhere for it to go it goes nowhere. It’s that simple.

Richard, here are some hastily put together thoughts on your blog from a business perspective, from a small number of mainly SME business people involved in emerging technologies whom I have spoken to. Nothing you all don’t know I don’t think, but I thought to bring that perspective to the discussion.

I was surprised at the strength of feeling of some about lack of understanding of the innovation process by many academics and its impact on innovation. When businesses are struggling to raise the necessary capital, promising technologies failing to make it through the tricky middle stages – the ‘blue skies‘ debate looks rather self-indulgent to some.

I wonder if there some more which could be done to bring about greater understanding of each other’s perspectives? The Research Councils and Learned Society’s in particular could, it was felt, do more to foster understanding of the innovation process and the business perspective and foster a more mutually respectful mindset.

There was concern in some areas that academia had a disproportionate influence over policy to the detriment of the innovation process.

There is a feeling that such a lot of money is spent through the Research Councils but not nearly enough in developing the companies which may come out of that technology transfer process, particularly across that middle stage ‘valley of death’. The UK seems to be good at starting companies by not at making middle-sized companies.

Business needs the ‘right tools’ as well as incentives. The Fraunhofer concept, as always, was considered hugely valuable to ‘de-risk’ a technology, (eg make it fit for market), making VC investment more focused and fruitful. The Catapult Centres are being watched with interest for that purpose as are other recent funding initiatives.

Richard’s post was felt to focus too much on inputs not outcomes. Perhaps needing to include a measure of value for money ie what’s come out of the R&D investment in all the countries to determine whether the money was well spent.

It would be interesting to quantify the number of SMEs started over the period covered especially those that came out of universities in all countries and what happened to them – did they grow? Were they acquired by a large company? Are their products still on the market? Are the people still successful? It was felt more needed to be done to identify the successes and how they got there.

Perhaps also these stats may have under-reported R&D, particularly in SME’s, which may also have skewed the stats in favour of Germany where the larger company R&D is easier to track.

The concern that privatisation didn’t lead to a transfer of the associated R&D to the business sector may, it was felt, be as significant as Richard suggested, and may reflect that the Government funded R&D was ill-conceived, open-ended in terms of funding, especially for the Defence sector, whereas the business-funded R&D is market driven and focussed.

Well I quite liked Richard’s piece which, as usual from Richard, was though provoking. Rather than concentrating on one set of statistics it is more germane to address the question near the end, namely whether the UK is in danger of becoming a low growth, low productivity, low innovation economy. Our work with data provided by the World Economic Forum and INSEAD, looking at on nanotechnology commercialization indicates that this may indeed be the case, and it’s not something that you can blame our world class academics – who consistently punch well above their weight on the world stage – for.

I have discussed the low innovation problem in UK industry with the last two governments and found that while they are aware of the issue, they are clueless about what to do about it. Any discussion of the role that technology plays in the economy either focuses solely on the IT sector, where is the UK Google, Apple etc?, or gets nowhere as ministers are often briefed by a mixture of hardcore academics and researchers using Google as their primary source. What is not well understood is that the fruits of academic research can take ten to twenty years to be turned into profitable businesses, and that this is a turn off for most investors who see it as simply too risky.

There are some mechanisms that government can use, the TSB specifically supports early stage high risk technologies – although only to the tune of 60% which is small compared to some of the US government programs. But what is needed is a joined up and grown up discussion about how to ensure that the UK becomes a 21st Century economy by leveraging our existing academic research base effectively. This isn’t something blaming academics/business/government or coming up with a fancy new initiative to create yet another Silicon Valley will solve. It is an issue that requires some longer range thinking than we have seen of late, something that is commonplace in some of the economies that Richard cites. History (and most economists) show that the way to increase productivity is through technology, whether the plough, Spinning Jenny or IT.

Bringing together business (and not just the large companies who usually get a seat at the table) with academics and policy makers with the aim of creating a rational, acceptable and above all workable vision of the UK economy in 2030 is what us required. If we don’t do that we will have another 30 years of stumbling around in the dark blaming each other for failing to find the light switch.

Gosh, Hilary, it seems as though there’s a certain amount of shooting the messenger going on here! Since I basically agree with the characterisation of the ‘blue-skies” debate as being self-indulgent, and have said so prominently in public, to the dismay of some of my academic friends, perhaps I can be forgiven for feeling shot at by both sides.

To go back to Dick’s anecdote and Nick’s comment on it that Labour was ideologically unwilling to fund industry research directly, this is true, but this was by no means originated by Labour. It’s the natural consequence of the free-market driven ideology introduced by the Thatcher government, which thought that intervening in industry’s business in this way would distort the natural workings of the market. In the case of basic science, a (moderate) free-marketeer can argue that there’s a market failure that means that an individual company can’t capture the full benefits of that research, which flow instead to society at large – and so in this case it is justified for the state to support research, where it wouldn’t be justified for nearer market research of the kind carried out by industry. Such a free-marketeer might naturally say that if the offshore oil and gas industry, with their billions of pounds in turnover, weren’t prepared to stump up the £5m formerly provided by EPSRC then they clearly didn’t value the results enough. The 1997 Labour government largely accepted this free-market rationale for not intervening in downstream industrial-led research. “Where’s the market failure?” is a refrain I’ve heard endlessly. This only began to change when Mandelson returned as Business Secretary in 2008 – his experiences in Europe had convinced him that the free-market driven policy of non-intervention in downstream industrial research needed to be rethought. The results were the indian summer of industrial intervention – particularly in the automotive industry – at the back end of the Labour government following the “New Industry New Jobs” policy document, and the commissioning of the Hauser report, which led to the setting up of the Catapult Centres. The change in attitude when in the Coalition government arrived is summed up, to us S.Yorkshire folk, in the two words “Sheffield Forgemasters”. Now the Coalition, at least in part, seems to be rethinking its position, with David Willetts and Vince Cable explicitly talking about industrial policy (though it isn’t at all clear that No 10 and the Treasury share this view).

I do know quite a lot about the problems high-tech companies face making it over the “Valley of Death” – one of my responsibilities at Sheffield is our spin-out activity. Currently we’ve got three good and promising companies at various stages of fund-raising at this crucial stage, some others struggling to hang on. We’ve just had a success with an excellent company, that’s got across to the other side of that valley – it’s grown fast, is profitable and employing more and more people, and has just been sold for $37 million. Of course the $ indicates that the company was sold to an American company, and you might well regret that control of the company hasn’t stayed in the UK and subsequent growth may well not benefit the UK – but the investors wanted a return on their money, and who can blame them given the poor returns enjoyed by venture capital funds in the high tech sector since the dot com bust. I think some people might be surprised how much state money has actually gone into this kind of activity through things like the University Challenge funds and the late RDAs – in fact in the really bad years after 2008 it’s pretty much this alone that have kept things afloat at all. Of course to a free marketeer this sort of state intervention is anathema – they’d say that if the market won’t fund these companies, it means they aren’t worth funding.

It’s an entirely fair point that my piece was focused on input measures, and it would indeed be interesting to answer all those detailed questions about outcomes. I would be feeling more guilty about not going in to those issues if my piece was the report of a six-month research project rather than a blog post written on my sofa on a Sunday evening. In fact, as my post makes clear, its aim was to stimulate precisely such a discussion of outcomes – as I write “Surely now is the time to examine the outcomes of the UK’s thirty year experiment in innovation theory.” But what I do strongly think is that there is a case to answer. Maybe the UK has used its smaller R&D investment in a marvellously targeted way and Germany has frittered its larger sums away in vanity projects. But if we look at the macro level – the health and productivity of industry in the two countries, the overall performance of the two economies – do we really think that’s likely? At least, the question warrants investigation.

At the end of it, I agree with Tim. The first stage is to admit to ourselves that there might be a problem here. Then, rather than finding someone to blame, we need to set about doing something about it.

@Tim, I think it’s pointless to get into a blame game. Academia is not to blame for sure but it is also not the solution. We need to try and learn from our mistakes, one of which is to believe that we can be a research lead economy. A mistake in the minds of the present Govt. but they may be changing.

“…in danger of becoming a low growth, low productivity, low innovation economy.”

Becoming? We arrived at this point some time ago. We have had poor productivity in the UK for a generation, we have not set the world on fire for growth since the industrial revolution and most metrics show we are poor innovators but good researchers.

That’s the other big mistake. One of the first things one has to do when trying to solve a problem is to accurately define the problem in the first place. I don’t think we are close. We are not in danger of decline we have arrived.

You hit it on the nail with “clueless”. You don’t find the same level of ignorance with German politicians for example. We have a cultural/political challenge.

Which leads me to….

@Richard, I don’t think you are being shot at. Perhaps securing some further ammunition for that PhD research project! 😉 I think someone needs to do a serious research project in this area. You should look up the OECD report on innovation (you have to buy it), which may resonate with your assessment here. I think I will do the IP one, when I have a blog.

What you have nicely illustrated is the problem with British politics and the short-term view. No long-term thinking by people who know what they are doing. Start with the Wilson Govt. and it’s been a very slippery slope ever since. That is a big distinction with Germany, Korea, Japan and China. Largely stable long term political situations, better industrial (not R&D) policies and I will suggest a much smarter political class. The USA does not need to be so long term simply because they have speed, crack on and have scale and power to reinvent themselves every 20 years (look at the churn in the Fortune 500). We by contrast are slow, dithering and inept.

An article in the Guardian today highlighted the position of the UK vs Germany on renewable energy. The single most important sentence ended with “……the UK is 20 years behind Germany.” The cleantech groups are alive with debate about why we can’t get our act together. Despite this our political classes including Two Brains Willetts keep talking about maintaining the UK’s lead in renewable technology. What lead? Wake up! We just keep whistling in the dark.

We are not leading anything and a tweak here or there in terms of R&D spend is not going to change that. The 30 year experiment was in fact an experiment to see what happens when we turn off innovation and de-industrialise. We need to reverse that quickly; the only thing that matters in a globalised economy is industrial depth and strength. We can forget Nobel Prizes. What is this UK obsession with honours anyway?

Richard,

Just wanted to share a hot of the press flavour of what I am talking about on IP and the industrial issue. This is an item about the European Patent Office filing statistics.

http://bit.ly/KINiwN

Outputs? Patent stats are a proxy for innovation (not invention, not quality of research, but industrial activity). I know academics and others will dispute but they are wrong. This is just a snippet. It does not give you the full picture but when you dig under the headline information the real picture starts to come out. I don’t have the time or space to develop that here and support all my bold statements but will highlight some key points.

First thing to note is that the UK is in decline, whilst many others are not. Important point is that this is no new it’s been the same for a decade or more. That is why we file 50% less than France not the 18% of a few years ago.

Look at the table and spot the UK Company in the top 25. Notice where the top 25 are based. The important points? This has not changed for years and has in fact worsened. More damming is that when you go to the top 100 (not shown) you still struggle to find UK companies on the list. There has been a massive real and relative decline in the UK.

In 1981 I used to work for one that was up there. It was called ICI….who?…. many people will ask today. 30 years ago ICI were up there with all the surviving and successful chemical companies on this list. They spent a fortune on R&D. What happened? Who in the UK could have purchased your £37 million spin-out?

Tim rightly talks about “clueless “ politicians. The UK Patent Office and 10 Downing Street made a lot of PR and spin out of the large increase in the grant of UK patents last year. The headline was that this was good news for the UK and proves we are innovating etc blah blah. Not a chance. Scratch the surface. These patents are overwhelmingly owned by overseas companies. The number of companies filing patents in the UK is in decline and the number of applications that they file is in decline. Good bits of news? The number of applications by what we call “self-filers” (Dragons Den hopefuls) is on the increase. Also, our largest filers of patents are…… our Universities…..not UK industry. The UK Govt believes that we just need to get SMEs back in touch with patents. Hence the UKIPO Hargreaves Review and the “outreach” activities and proposals. If this was not so serious it would be laughable. Outreach to whom? Disengagement is not the problem…..we have witnessed an extinction event in the UK but have just not realised it yet.

@Nick,

it’s something we have ben trying to address see our paper with the World Economic Forum at

http://forumblog.org/2011/01/addressing-global-risks-requires-more-sophisticated-thinking-on-new-technologies-andrew-maynard-tim/

We’re making good progress on getting this up & running, but most of the support has come from the US, Asia, Germany & Switzerland. If only some of the UK universities were as enthusiastic about hosting the project we may be able to start addressing the issue.

Nick, the case of ICI is indeed an interesting one in which one can trace the decline of an example of exactly the kind of organisation that could work at scale to bring innovation to market. There was the hostile bid from Hanson, the demerger, the mistimed and mispriced purchase of National Starch, the forced sale of businesses to clear the resulting debt, with many of the disposed of businesses being sold in highly leveraged private equity deals, and the final acquisition of the rump by Akzo-Nobel. One can see some interesting themes – the pressure from shareholders wanting a quick return, an emphasis on the deal as opposed to growing new profitable businesses through innovation, excessive debt loading. I’d really like to see a careful case study of this story, I’m sure one must exist (and there must be others too, for companies like GEC). But the consequence is clear enough – ICI’s former rival BASF survives to make 4th place in your top 25 patenters, but of UK companies there are none.

Part of why I like R+D is that there isn’t alot I want to buy. I can’t buy a mailorder teenage bride easily. Or weed. I can’t find out singles near me who look like Kournikova. I can’t find singles who study peat moss and tree-under carbon sequester. I can’t rewatch for a reasonable rental, the Jan 8th 2011 Det-Van game, the J.Carrey SNL episode I missed to watch it, the 2003 NJ Ott playoff series.

For AGW and pandemics, the event details can be altered, as well as mitigation and prevention. Two diferent examples. Even truly evil people like W, both N.American Chambers of Commerce, the Kochs, tar CEOs; they can only command about 5-10M persons worth of emissions each. You need 1000 of these people to equal a bioterrorist. And likely for other reasons, the solutions to AGW can be a public discussion. I like cheap metal wind turbines (USA has research studies ready for 2013, hopefully a few different types can be employes) and a utility-scale metal battery for power banking that is solution-phase: antimony on top, salts in the middle, and magnesium on the bottom. I think there is gov latitude for prototypes, but I’m not sure where the market kicks in, yet. It all seems to be about materials costs.

For stopping bioaccidents and bioterror, you can’t just put the plan details public. Unless Romney wins and China buys more tar. I’m making 1/2-1/3 min wage now so try and stop me.

You have some research that details some basic disease pathology. You have some that might lead to treatment/vaccine, and some far away sector research that might yield tools for bioterror. You can get a timeline for prevention/mitigation tools, and a timeline for when the big one will hit….but lobbying for prevention/mitigation requires public knowledge of some of the details: catch-22. You can pay to shift the event back, the prevention/mitigation forward….how much to pay? And how much will the (public) prevention/mitigation budget grow if bioterrorism becomes inevitable? If not much, you are almost hoping for a Spanish Flu event.

I guess you can look at it as various shifts to GDP. Counting GDP in the future for starters. I’m annoyed in N.America the Nominees for the Board of Directors (who are generally rubberstamped by shareholders), aren’t selected by the shareholders from grassroots. This makes the Board useless and certainly I won’t shed any tears if the children of golfers here get flu-AIDS one day.

What happens is enough environmental change happens, during a pandemic, that people start to wig out and I assume break stuff or kill. Stuff like going hungry increases odds of government downfall. Utilities should be hardened to be capital intensive. I think geothermal, wind and future off-grid solar, are ideal. Coal is impossible to maintain and I’d guess gasoline and oil hard. A battery economy may be best if the charging is easy enough. For healthcare services, can have immune volunteers be the in home team for tele-Dr. hologram conference. The holotool useful for desensitizing a population to a pandemic environment.

…and the investments aren’t equal. So can in theory do more with less. The USA is only spending $20M or whatever, looking at different common metal wind turbine component, turbines. And it will result in the quicker scaling of a mass producible design. Canada paid for a car PEM and got a forklift, but also made result diabetes and Ebola breakthroughs. I get the impression a lot of future Q-of-L gains will come from costing stuff like this accurately.

Richard, The recent Nesta report illustrates the problem I feel. The UK science spend is sort of irrelevant to UK industry if UK industry does not invest to use it. In the past 20 years the politicians egged on by the Science lobby have I am afraid taken their eye of the important ball and that is industrial R&D and innovation. That is why we are second in the world for service exports but are down the list for goods/things of high value that others will buy. You can almost regard our University R&D spend as a “service” export and the Nesta report nicely highlights how we are not capturing this in the UK. Not the fault of the Universities or the research community in UK Universities. However, I do wish the “Poster Boy” of British science would stop banging on about the incredible importance of the science spend to UK industry and wake up and smell the coffee. Until UK academia wake up and realise that their future resides in a reversal of what we see in this Nesta report and a better engagement of UK Science with UK industry they are doomed IMHO.

http://www.nesta.org.uk/home1/assets/features/plan_i

http://www.economist.com/node/21559355?fsrc=scn/tw/te/ar/tradeincommercialservices