This is the first of a series of three posts in which I bring together some thinking and reading I’ve been doing about the UK’s current productivity problem, and its relationship to innovation and to research and development.

(Added 2/9/2015: For those who dislike the 3-part blog format, the whole article can be downloaded as a PDF here: Innovation, research and development, and the UK’s productivity crisis)

In part 1, here, I take stock of the scale of the UK’s productivity problem and discuss why it matters so much, both economically and politically. Then I’ll set the context for the following discussion with a provocative association between productivity growth and R&D intensity.

In part 2, I’ll review what can be said with more careful analyses of productivity, looking at the performance of individual sectors and testing some more detailed explanations of the productivity slowdown. I’ll pick out the role of declining North Sea oil and gas and the end of the financial services bubble in the UK’s poor recent performance; these don’t explain all the problem, but they will provide a headwind that the economy will have to overcome over the coming years.

Finally in part 3 I’ll return to a more detailed discussion of innovation in general and the particular role of R&D, finishing with some thoughts about what should be done about the problem.

The scale of the UK’s productivity problem

The UK’s current stalling of productivity growth is probably the UK’s most serious current economic problem. In terms of output per hour, the last five years’ productivity performance has been by far the worst period in the last 45 years. Many other developed economies have had disappointing productivity growth in recent years, but the UK’s record is particularly bad. Amongst other developed economics, only Luxembourg and Greece have done worse since 2007, according to a recent OECD report on the future of productivity (see table A2, p83).

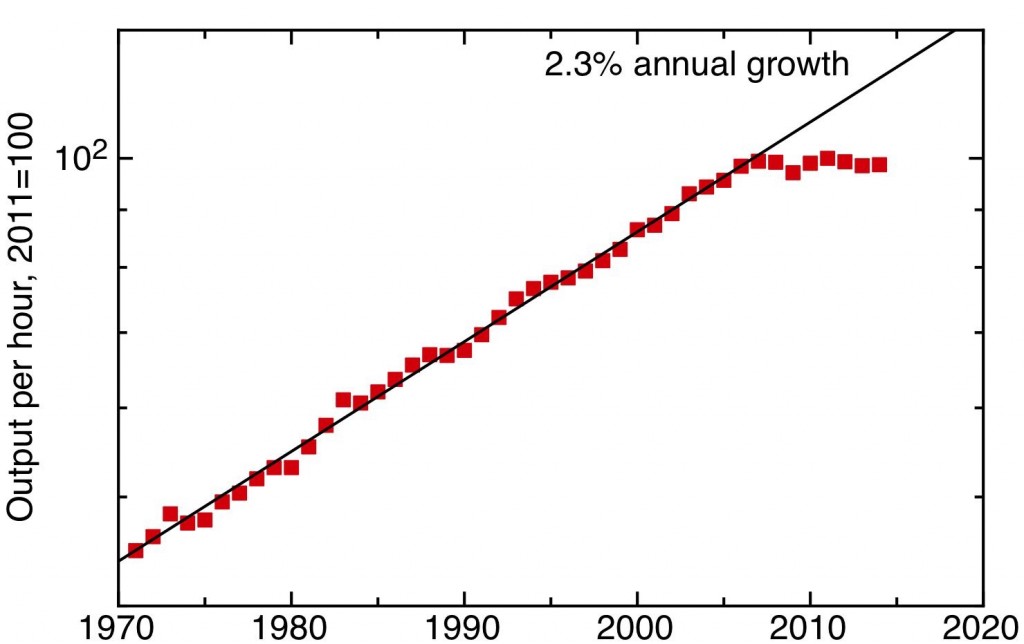

Labour productivity since 1970. The fit is an exponential corresponding to constant growth of 2.3% a year. ONS data.

My plot shows the UK’s labour productivity – defined as the GDP generated per hour worked – since 1971. What’s striking about this graph is how closely productivity has followed a trend of constant 2.3% a year growth. What conventional wisdom tells us was the economic chaos and stagnation of the 1970’s – the three day week, the bursting of the Barber boom, the IMF bail-out, the Winter of Discontent – barely makes an impression. LIkewise, the deep early 80’s recession, the subsequent recovery, the bursting of the Lawson boom, the post ERM recovery – again, all are barely visible as small fluctuations around the relentless compound growth of productivity. This steady progress changed abruptly with the financial crisis in 2008. Since then productivity growth has essentially stopped.

By 2014, the productivity gap between what we’d have expected on the basis of the pre-crisis trend and current performance had opened up to nearly 20%. This is a once-in-a-lifetime event; if we can’t work out why this happened and reverse it the political and economic consequences will be serious.

Why productivity matters

Fundamentally, rising living standards and rising productivity are directly linked. Average wages in the long run should rise in proportion to rising labour productivity, unless there is a substantial change in the division of returns between capital and labour (which has not yet happened in the UK, unlike the USA). Overall economic growth can only come from a combination of growth in productivity and growth in number of hours worked. In the UK in the last five years, such economic growth as we have seen has arisen from employment growth, largely amongst recent immigrants. The government needs there to be significant GDP growth over its term of office in order to bring public finances back into balance; since much further expansion of employment growth is unlikely, a recovery in productivity growth is essential if the government is to meet its deficit reduction targets.

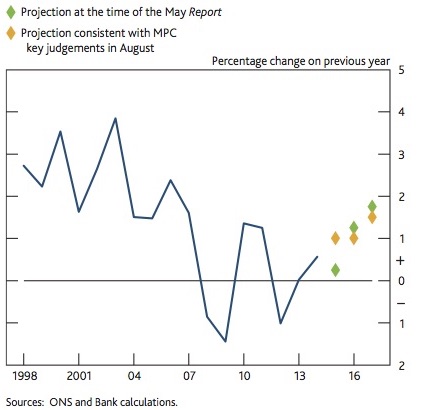

The official economic forecasts that underpin the government’s borrowing projections assume that the recent productivity stagnation is a blip that we can expect to recover from through the natural self-righting tendencies of the economy. For example, the August 2015 Inflation Report of the Bank of England detects the beginning of recovery, and projects an increase of productivity growth to 1.5% by 2017, as part of the slow recovery to a long term average of 2.25%, as shown in the plot below.

What if this recovery has not yet started? What if the average long term rate of productivity growth is now different? For example, here’s some modelling (The Macroeconomic Impact of Liberal Economic Policies in the UK, Couts and Gudgin, Judge Business School, Cambridge) taking into account structural changes in the UK economy, with the pessimistic conclusion that the new stable long term average may now be closer to 1.4%

It is the Office of Budgetary Responsibility that has the duty of independently assessing the government’s economic plans, and their July 2015 assessment does indeed consider the consequences of lower productivity growth. It has what it engagingly calls a “‘history repeats’ scenario, in which we assume that we have made similar errors in our latest forecast to those that we made in June 2010”. This assumes that productivity growth stays stuck at 0.4%. The conclusion is stark: “the Government would miss all its current and proposed fiscal targets”. In this event, the Government will have to fight an election with a background in which despite deep austerity, the public finances remain unrepaired, and living standards continue to stagnate.

It’s difficult to look at the noisy data in the productivity growth rate chart below, and say that scenario looks any less plausible that the Bank’s more rosy projection of recovery. To understand which is more likely, and whether there is anything policy can do to steer the outcome, we need to have some better answers about where the slowdown in productivity has come from.

The Bank of England’s current expectations for future productivity growth. From the Bank’s August 2015 Inflation Report (figure 5.7)

The UK, weak for research and development, weak for productivity growth – what’s the connection?

Economists agree that the fundamental origins of productivity growth are to be found in innovation, both technological and organizational. One key measure of the resources devoted to technological innovation is the R&D intensity of the economy, so it is natural to ask whether the current slowdown in productivity is connected to the UK’s long-term record of lower spending on R&D (both public and private sector) compared to other developed economies.

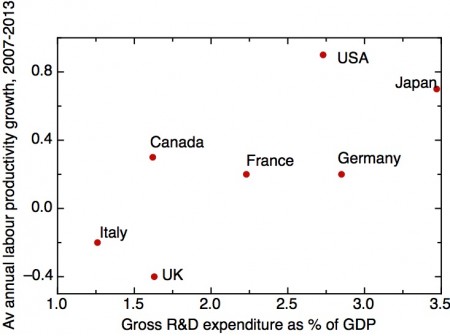

The data for the G7 group of developed economies is shown in my plot. The UK is close to the bottom of the league for its R&D intensity, and its productivity growth has been the weakest of all the big developed economies. But it does need to be stressed that the correlation between productivity growth and research and development is not straightforward – productivity growth varies across different sectors of the economy, and can be affected by different factors such as the degree of capital investment. We need a finer grained analysis to understand the links.

Average annual labour productivity growth since 2007 vs current gross expenditure on research and development as percentage of GDP for G7 nations. Labour productivity growth was from table A2, p83 of The Future of Productivity, OECD April 2015, GERD from OECD Main Science and Technology indicators.

Continue to part 2