I have a much shorter version of my earlier three-part series (PDF version here) on the connection between the UK’s weak and worsening R&D performance and its current productivity standstill on HEFCE’s blog: Innovation, research and the UK’s productivity crisis.

The same piece has also been published on the blog of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute: Continuing on our current path of stagnating productivity and stagnating innovation isn’t inevitable: it’s a political choice, and it also appears on the web-based economics magazine Pieria.

The longer and more detailed post also formed the basis for my written evidence to the House of Commons Business Innovation and Skills Select Committee, which is currently inquiring into the productivity problem: On productivity and the government’s productivity plan (PDF).

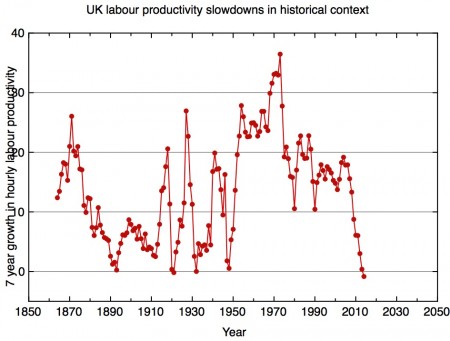

Finally, here’s another graphical representation of the productivity problem in historical context, using the latest version of the Bank of England’s historical dataset “Three centuries of macroeconomic data”. It shows the total growth in hourly labour productivity over the preceding seven years; on this measure the current productivity slow-down is worse than that associated with two world wars and a great depression.

Seven year growth in hourly labour productivity. Data from Hills, S, Thomas, R and Dimsdale, N (2015) “Three Centuries of Data – Version 2.2”, Bank of England.

Richard, maybe the UK government believes in nothing except a hypothetical fantastic computing machine. Surely, the Science Minister is suffering from extreme pessimism and doubts the UK can compete in the sphere of incremental improvements of existing technologies and therefore a game changer is required. What else could possibly restore lost credibility in science and engineering at this point in time?

It seems odd to me that no one (as far as I know) has correlated the drop in productivity in the UK with the growth of usage of “media” applications such as facebook and twitter. The personal use of such applications for during work time can only lead to a loss in productivity. Whilst employers can effectively inhibit the use of such applications through the “company” office network, the use of personal smartphones overcomes such measures and also spreads the availability of such applications to non – office based employees.