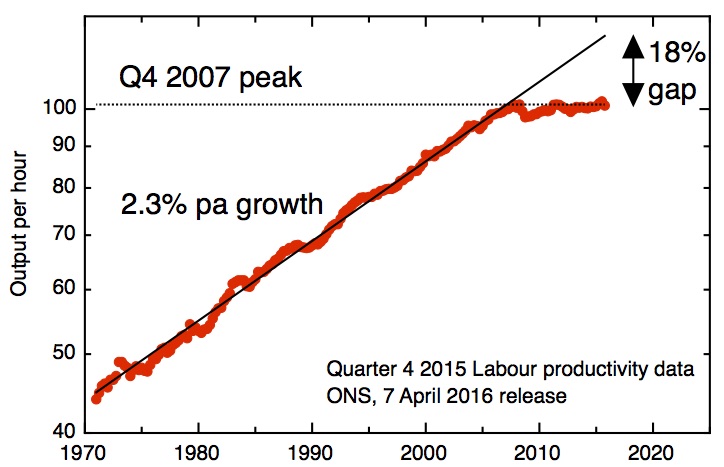

The UK’s Office of National Statistics today released the latest figures for labour productivity, to the end of 2015. This shows that the apparent recovery in productivity that seemed to be getting going half way through last year was yet another false dawn; productivity has flat-lined since the financial crisis, with the Q4 2015 value actually below the peak achieved in 2007. This performance puts us on track for the worst decade in a century. Poor productivity growth translates directly into stagnating living standards and lower tax revenues for the government, meaning that, despite austerity, all their efforts to eliminate the fiscal deficit will be in vain.

As this is perhaps the most serious economic problem currently facing the UK, it’s good to see the issue becoming more widely discussed. It’s an issue I’ve been thinking about for some time; my post on the political implications of the productivity slowdown, as revealed by this March’s budget and its aftermath, is here: The political fallout of the UK’s productivity problem. Last summer, I wrote a series of blogposts exploring the origins of this productivity slowdown. I’ve written a draft paper based on a substantially revised and updated version of those posts:

Innovation, research, and the UK’s productivity crisis (1.4 MB PDF).

Labour productivity: output per hour. ONS Labour Productivity Dataset, 7 April 2016.

I think you are missing a “head-wind” in your analysis.

In moving to renewable energy we have taken the decision to massively reduce the productivity of the energy sector in terms of economic output, electrical power, per hour worked. (also per acre of land, but that is not the issue here)

The same is true of our decision to recycle more, at least where such recycling is loss making and therefore has a negative economic output.

In a democracy we can decide to do these things, but they have a cost. We should not hide from the fact that a decision to be “green” will often have negative consequences to productivity, at least when measured without putting a value on the externalities of fossil fuels.

Off Topic: I found your blog via Econtalk, thanks for an interesting discussion.

Yes, that is a fair point, and that’s why I included, as one of the strategic goals that the state needs innovation to achieve, “the need, for example, to develop low-carbon energy at a cost that is competitive, without subsidy, with fossil fuels” (emphasis added here). One can (and indeed should) argue that exploiting fossil fuels gives us higher GDP and productivity now at the cost of lower (possibly much lower) GDP in the future when serious negative consequences of climate change show up later. But accounting for the externalities of fossil fuels properly in an international context is going to be politically very difficult and the more that one can bridge that cost gap by bringing down the cost of low-carbon energy the easier it will be to take the action we need.

I do have some sympathy with the argument that we have spent too much money prematurely deploying renewable technologies before they were cheap enough, rather than using (a fraction of) that money to do RD&D to bring their prices down to the point at which they could be deployed with less of a (or indeed zero) productivity hit, but if you make that argument you have to be serious about genuinely doing that innovation at a scale and pace that the problem demands. Then in turn we need to recognise how scandalously little we have been spending on energy RD&D over the last thirty years and commit to correcting that. See this earlier post We sold out our energy future.

I’m glad you liked the Econtalk discussion.