I call myself a rock climber, and sometimes I manage to do some climbing too. This summer I’ve been out a few times with a new climbing partner, Mike. Mike’s a writer – M. John Harrison – whose most famous work is the science fiction trilogy Light, Nova Swing and Empty Space. I’ve written about these brilliant books before. But it’s another novel of his that these climbing trips have brought to mind – his 1989 novel “Climbers”.

“Climbers” is a beautifully written book, formally clever and an utterly perfect evocation of a certain time and place, a certain milieu – the Peak District climbing scene in the late 70’s and early 80’s. This I know, because I was there – at least, as a youth learning to climb myself, I was on the fringes of this scene.

This is how it happened. 1979 was the year I left school. That summer, my friend and climbing companion, Mark, having been expelled from school (the reasons for which are another story), had moved to the Peak District. His parents had divorced, and he went with his mother, first to a mobile home outside Chesterfield, then to the village of Tideswell. I visited him there, staying in his mother’s tiny cottage and hitching to the crags, Mark in a greatcoat, with their Jack Russell sticking its head out of his rucksack, an ancient Karrimor Pinnacle that he’d stolen from school.

Rock climbing in the Peak was going through one of its periodic revolutions in standards – we’d read about these in the fanzine-like pages of the upstart “Crags” Magazine – and Mark wanted to be part of this. His favourite crag was Burbage, and it was there that he bumped into some people from Nottinghamshire, among them Alastair, from Hucknall, who worked down the coal mine as an electrician. Mark, pretty much by force of will alone, pushed himself from the moderate climbs we’d got used to doing, to being able to get up some of the extreme climbs that were approaching the leading edge.

The wetness of a Northern autumn and winter came; no-one was doing much climbing. I spend another term at school, to sit the entrance exam for Cambridge; after that I got a job in a Coca-Cola factory (Production Line Operative, Grade 2). Spring came, I left the job, and thought about climbing more, joining the loose bunch of people that had gathered around Mark and Alastair.

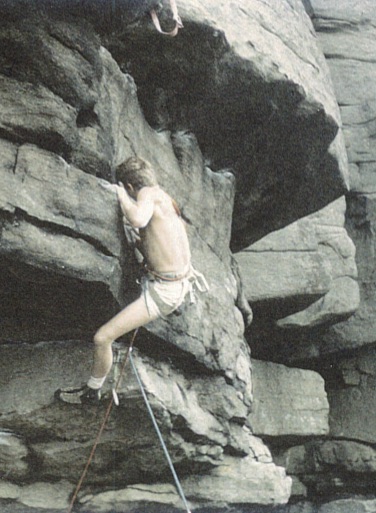

Neil on Tippler Direct, Stanage. The EB rock shoes and Whillans Harness identify the era – but he was characteristically ahead of his time when it came to shirtless climbing.

Mark came with his companion from Tideswell, Neil, himself at a slight loose end, having left his Bakewell school under a cloud (a misunderstanding whose details Neil to this day has never been entirely clear to me about). From Nottingham there was Chris, a lab technician for Boots, Billy – like me, waiting to go to university, and Pete, who’d recently left the Marines. So between us we had something of a team, with Mark the most ambitious and most technically accomplished as a climber, and Alastair at the hub of it all.

We’d get around by hitching (only Pete amongst us had transport), and for accommodation we’d sleep out in caves and rock shelters under the crags. The subject of endless pub discussions was: where’s the Best Doss in Derbyshire? For some it was Robin Hood’s Caves – a series of sandy, wind-eroded chambers high on Stanage Edge. They are roomy and clean, but a long walk and an awkward scramble from Hathersage. Froggatt Barn had its supporters – waterproof and spacious, but its position next to the car park meant it could be noisy with car-borne partygoers. Froggatt Cave is sanctified by history, with a fine view, but a tendency to drip in heavy rain. More desperate expedients were occasionally pressed into service – the shelters on the (unmanned) Grindleford Station, drafty and subject to the noise of passing trains, and the public toilets in the Black Rocks car park.

Among the best times I remember was a week or so of weather so perfect we didn’t need caves, and just slept under the stars, moving from crag to crag. Mark and Billy were pushing their grades, so Alastair and I were left as the B-team, ticking off the HVS classics – Pendulum on Stoney, Avalanche Wall on Curbar, Suicide Wall on Cratcliffe are the ones I remember.

Another time Mark, Pete and I made a rare trip out of Derbyshire, to Cornwall, in Pete’s van. Pete was a truck driver – this was the one useful skill he’d learnt in the Marines. More useful in civilian life, anyway, than being able to ski with a heavy machine gun on his back, or the more sinister capabilities that he would darkly hint at. He was built like a marine too, with a still-raw gash on his cheek, a bottle-scar from a bar fight in Montevideo. He’d always insist, though, that he was different from the other lads – they just wanted to go out brawling, but he’d prefer to collect flowers to press (not that I’ve ever detected any interest in botany in him in the nearly 40 years I’ve known him).

The author, eating chips in the back of Pete’s Morris Marina van. “Living the dream”, as the young people say.

This was a proper road-trip – from the Star in St Just to the urban climbing of the Avon Gorge. Sea-cliffs weren’t new to us – Mark and I had climbed in Pembrokeshire, and a year or two before we’d scared ourselves on Gogarth during a three day stopover in the Holyhead ferry terminal. And Pete had assaulted some Cornish cliffs as part of his Devon based Commando training. But now, for the first time, we had the confidence and ability to take on big routes in the harder grades. Climbs I remember include Saxon, Suicide Wall (another one) on the West Penwith tip of Cornwall, Crimtyphon and Caravanserai on the shaley sandstone of Compass Point, near Bude (before they collapsed into the sea), Pink Void and Undercracker on the big sandstone slabs at Baggy Point.

Perhaps most memorable was a route called Mercury on Carn Gowla on the North Cornwall coast. Like many sea-cliff adventures, it isn’t the climbing itself that makes the climb memorable, but the totality of the experience. This began with a 300 foot abseil, much of it hanging free in space after going over an overhang about 30 feet from the top, aiming for a small ledge just above sea level. The cliff drops straight into the ocean, and from it there’s not much you can see but sea, heightening the feeling of isolation and commitment you get on a big route. But at the same time as you’re conscious of the big space around you and the foaming sea below, you’re even more conscious of what’s right in front of you – the biscuity texture of the rock, the weirdly scratchy lichen, plants growing in pockets in the rock. Never did Pete’s van seem more welcoming to return to.

But this was a rare outing from our normal habitat of the Peak District – and in the Peak District, the centre of our world was Stoney Middleton, a scruffy village at the end of a valley lined with steep limestone crags. “A climber’s apocalyptic vision of the wasteland”, it was described as in the Paul Nunn guidebook to climbing in the Peak District. We loved this phrase, which summed up the road busy with thundering lorries, the noise of blasting from the quarries, thick white dust everywhere – and steep, scary limestone climbs, polished and awkward.

And yet this was the centre of Peak District climbing scene, with its famous routes, and the equally famous Lover’s Leap cafe and Moon Inn. Every Saturday, climbers from Sheffield and Manchester hitched or caught the bus along the busy main road, spent the day struggling on the test-pieces of the crag, and then piled into the Moon for the evening. Having been thrown out of the pub at closing time they’d spill out to find shelter for the night where they could – for some, in “the Woodshed” – the store for a local joiner’s business, while others preferred Windy-Ledge buttress. This was a broad ledge halfway up the biggest cliff in the Dale, sheltered from the weather by huge overhangs. I wasn’t so keen on it myself – you’d be woken very early by the rising sun, and there was always the worry that you’d plummet off the ledge having got up to sleepily relieve yourself in the night.´

Mineshaft cave (aka Tom’s roof), Stoney Middleton Dale. Is this the Best Doss in Derbyshire?´

In the crowds, you’d see climbers half-famous, some whose names you would read in the magazines describing their first ascents of harder, steeper climbs. Black Nick, Big Sid and Little Sid, Dirty Derek, Basher… they seemed miles away from us in age and experience (some were probably in their late twenties). Rubbing shoulders with them in the cafe, or in the pub, made us feel closer to the centre of things – though they hardly did a lot to boost our confidence. One day Mark and I came into the café having done “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” in Chee Dale, which still had some kind of reputation. “Can’t be that hard if you two did it” was the reply to our attempted boast. The café – a greasy spoon catering to climbers, bikers, quarry-men and lorry-drivers in equal proportions – kept a battered notebook behind the counter – the new-routes book – in which the great figures of the climbing world would record their accomplishments, and denigrate those of their rivals. There the controversies of the sport were played out in ball-point pen – and for those innocents and outsiders (often from the south) who thought their own efforts merited recording, a succinct “done years ago” was the usual, crushing, marginal note.

I spent a lot of time in Stoney – my favourite doss wasn’t Windy ledge or the Woodshed, but a smaller cave some tens of feet up a big rift in the crag called “the Mineshaft”. It’s dry, secluded, and can take a lot of rain before it starts to drip. This I tested during a long run of wet days, whiling away the time with Billy by rehearsing and testing his encyclopedic knowledge of Peak District climbing routes, move by move, piece of gear by piece of gear.

I did spend a remarkably long time not climbing. Without mobile phones or reliable transport, arrangements to meet people had to have a lot of latitude, with margins of hours stretching into days. I spent a lot of time on my own, and I read a lot. With my Adrian Mole-like auto-didacticism, I read Joyce’s Ulysses and Blake’s Poems and Prophecies, with the morbidity of late adolescence I read Wilson’s The Stranger and Al Alvarez’s The Savage God, and, like Van Morrison, I had Christmas Humphreys’ book on Zen.

The autumn of 1980 arrived, and things changed for me. I went to university, carried on climbing in the Peak District, but with the different rhythm that comes from fitting it into a day trip from Cambridge. Mark and I set our sights on higher mountains – I’ve written before about how that worked out.

Coming back to this summer, after re-reading “Climbers” and thinking about the memories of my own of that time and place that it had dislodged, I said to Mike that I thought I recognised some of the characters in his novel, and sometimes bumped into them to this day. Not surprising, he said, they’re all composites drawn from life. The only time when people don’t recognise them is when they themselves were the model. “Climbers” is a novel – a fiction – but its truth is in exploring the way people tell stories about themselves as they construct the character they want to be – and very significantly, the parts of the story they distort, they parts they leave unsaid.

I find it interesting to contrast my reaction to “Climbers” to that to another book that features people I knew well. That book is “This Game of Ghosts”, by Joe Simpson, a non-fiction account of his own times amongst the Sheffield-based alpine climbers of the mid-80’s. Mark – Mark Miller – has quite a big role in this. Simpson is a good writer (though not in Harrison’s league) but I couldn’t help thinking his account lacked some essential truth about Mark. It at once underplays or excuses his real failings (at the time I often thought Mark’s moral code, if any, would have been better suited to a steppe nomad than a 20th century Briton), but at the same time misses those aspects where he could be thoughtful, astute and even kind.

Perhaps it’s more difficult to be truthful in factual writing than in fiction. Perhaps Simpson’s publisher (and their lawyers) had some influence there. But perhaps the bigger problem arises from his need to enlist Mark and the others as minor characters in the story he was constructing about his own life. Which, of course, is just what I’ve done here.

Richard

It was wonderful to read your astute insights about Mark. However, I am not sure you have been very fair to steppe nomads in your comparison. However, it would take quite a writer to capture his phenomenal and compelling personality. He was, as you say someone of great warmth, affection and kindness, as well as less endearing qualities! I sat in few bivouac ledges as he talked about you, in particular, with great warmth and affection.

Thanks Tom! He would indeed be a great subject for a great writer.