The government published its long-awaited “Levelling Up” White Paper on February 2nd. This is a much expanded version of a piece I wrote for Research Fortnight, “Levelling Up R&D is about spreading power as well as money”, in which I look at the implications of the White Paper for research and development.

What do the government mean by “levelling up”?

It’s fair to say that the Levelling Up White Paper, published after a long delay last week, struggled to compete with other political events for the front pages, and what comment there was about it focused, somewhat unfairly, on its great length, its thumbnail history of 9 millennia of urbanism, and its invitation to compare our Northern and Midland cities with renaissance Florence. But for those interested in the UK’s research and development landscape, it would be wrong to underestimate its significance.

For those who have been wondering what “levelling up” actually means, the White Paper does offer some concrete answers. Correctly, in my view, it puts the UK’s regional disparities in productivity centre stage. It offers some detailed analysis of the UK’s regional problem; for all that “industrial strategy” is not a “brand” currently in fashion with the government, the mark of the prematurely terminated Industrial Strategy Council, as transmitted through the person of Andy Haldane, now head of the government’s “Levelling Up Task Force”, is clear. In addition to much discussion of the data, there is an analytical framework based on a consideration of different types of capital, their unequal distribution across the country, and – crucially – a discussion of the vicious circles that can lead places into a self-reinforcing decline.

The role of research and development in levelling up

Research and development, together with skills, contribute to a place’s “intangible capital”, and, echoing an argument myself, Tom Forth and others have been making for some time, the connection is made between the unbalanced distribution of government R&D expenditure across the country and regional disparities in economic performance. Under the overarching goal of boosting “productivity, pay, jobs and living standards by growing the private sector, especially in those places where they are lagging”, one of the 12 “Levelling Up Missions” promises that public investment in R&D outside the Greater South East will grow by 40% by 2030, and by one third in the current spending review period (i.e. by FY24/25). The aspiration is that this increase in public sector R&D should “crowd in” roughly double the amount of private sector R&D.

Although it’s been pointed out that in many areas the Levelling Up White Paper isn’t supported by new money, this is not actually true for R&D. The October 2021 Comprehensive Spending Review did commit the government to a substantial rise in government R&D spending – about £5 billion, taking spending from a bit less than £15 billion to £20 billion. The commitment to a spending uplift of a third outside the Greater SE doesn’t, therefore, represent a real rebalancing of the current situation, and it actually represents a dilution of the commitment of the October Spending Review, which promised that “an increased share of the record increase in government spending on R&D over the SR21 period is invested outside the Greater South East”.

Given that the CSR commitment is reiterated in the White Paper, perhaps we should regard these targets as represents a floor to to the ambition, and they do at least mean that the current imbalances won’t get any worse. To be fair to those managing science funding agencies, it should also be recognised that, given that they have already taken on substantial multi-year commitments, changing the overall distribution of funding isn’t something that can happen very quickly.

Where is this new money going? It’s important to remember that, although academics tend to focus on the research councils, much public R&D is carried out by government departments. When we look at where the uplift in funding is concentrated, we find that the core UKRI budget, comprising the research councils and block grants to universities and research councils, does have an increase of £1.1 bn between 21/22 and 24/25, a 23% increase in cash terms. In percentage terms, though, the really big winners are departments like the Ministry of Defence, The Department of Health and Social Care, and the agency Innovate UK, which between them see an increase of 64%, representing a £2.7bn cash uplift.

If the promised one third increase in R&D spending outside the Greater Southeast is to be funded from the uplift committed in the spending review, much of the heavy lifting will need to be done by these more mission focused and applied funding streams. However, it is fair to say that the details of how this commitment will be met are not yet fully fleshed out in the White Paper.

How UKRI can support levelling up (and why it should)

UKRI gets a new organisational objective, to “Deliver economic, social, and cultural benefits from research and innovation to all of our citizens, including by developing research and innovation strengths across the UK in support of levelling up”, and an instruction to increase consideration of local growth criteria and impact in R&D fund design. It will be interesting to see how the organisation responds to this new mandate. Some may feel that UKRI shouldn’t take explicit measures to rebalance the distribution of R&D across the country, as this might compromise its primary commitment to funding excellence in science. I would certainly agree that UKRI needs to avoid funding poor quality research, but I’d make two points about the question of excellence.

The first is to point out that, for many in the research community, the most prominent funder of purely excellence based research for the UK at the moment isn’t part of UKRI at all, but is the European Research Council, with its mission to “support investigator-driven frontier research across all fields, on the basis of scientific excellence”. The ERC delivers this mission through the rigorous peer-review, by acknowledged international experts, of proposals whose quality is driven up by healthy competition from a whole continent’s worth of leading scientists. Much of UKRI funding, in contrast, is influenced by strategic priorities set by the research councils themselves. Of course, the UK’s ongoing participation in the ERC, like other parts of the EU Horizon programme, is now under serious question, but that’s another story. Perhaps the most important lesson we can take from the success of ERC in supporting excellence, though, is that it is entirely people-focused. Places aren’t excellent, people are.

The second point is to note that UKRI’s current aspiration is to be a steward of the whole research system. This stewardship certainly should include supporting excellent researchers wherever they are to be found, but it should also involve creating the environments that support those researchers. Research councils have in the past, quite correctly, taken on some responsibility for building those environments, so it is a natural extension of those activities to widen the range of places which do provide those environments. They can do this by building capacity, and by developing partnerships.

UKRI has a responsibility for maintaining the capacity of the UK system to do good research. This starts with helping to provide the infrastructure for that research, whether that is by providing funding for strategic equipment in universities, (in England) the block grant support to universities through quality related funding (QR) from Research England, through to creating and supporting entire research institutes. Research councils have rightly intervened to maintain the UK viability of some fields of research deemed strategically important. And there is a continuous, entirely justified, commitment to support the talent pipeline for research, and supporting good training environments for PhD students has become an increasingly important part of the research council’s business. It is a natural extension to UKRI’s stewardship of the UK’s future research capacity to give more weight to the geographical dimension of building that capacity.

Partnership remains another very important dimension of UKRI’s work, both internal and external. The whole point of creating UKRI as a single organisation was to promote more partnership working between the component parts of the organisation, the research councils, Research England, and Innovate UK. Research councils like EPSRC are rightly proud of the large proportion of their grants that involve some partnership with industry, and high profile recent initiatives include EPSRC’s Prosperity Partnerships, large scale research programmes with matched funding from industry, to deliver a research agenda co-created by academic and industrial researchers.

It’s welcome that the most recent prosperity partnership call offers an invitation to articulate the degree to which these partnerships support place-based outcomes, such as attracting inward investment to specific regions or otherwise supporting regional economic growth. It would be a natural extension to include regional bodies more explicitly as partners for research council supported research, and as co-creators of research strategy, in the way that R&D intensive companies currently engage with UKRI.

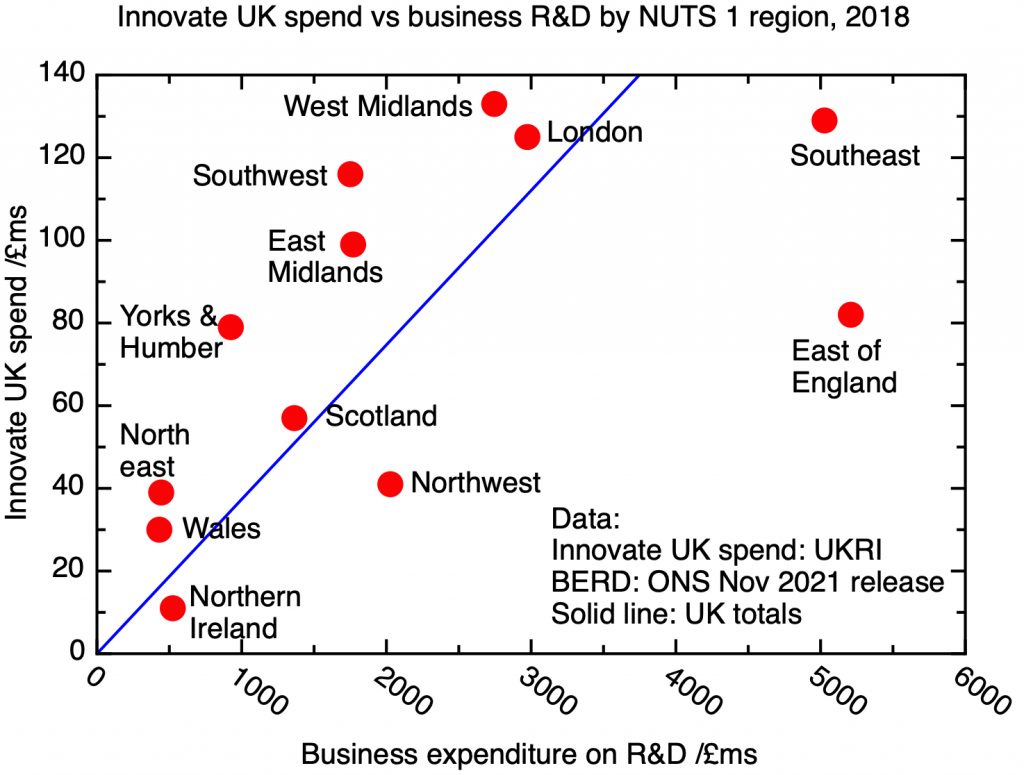

Innovate UK has different drivers from the research councils; as an explicitly “business led” agency one might expect there to be some correlation between the regional distribution of business R&D and Innovate UK’s investments. The relationship is shown in my figure –regions to the left of the line receive more Innovate UK money than you would expect from a simple correlation with business R&D, regions on the right receive less.

A comparison of Innovate UK expenditure with business R&D for 2018. Innovate UK data from UKRI, regional business R&D data from ONS BERD statistics.

This distribution doesn’t immediately suggest a straightforward explanation. One might wonder whether it reflects industrial sectors that are particularly well organised to receive support from Innovate UK – perhaps the importance of automotive for the West Midlands and aerospace for the South West and East Midlands is reflected in the above average Innovate UK support for those regions.

Another factor in determining these spending patterns is the location of the Catapult Centres. These receive core funding directly from Innovate UK, as well as participating in joint projects with industry that receive partial funding from Innovate UK, so the regional distribution of Innovate UK funding probably to some extent reflects the location of Catapult Centres.

It’s possible that the high London figure to some extent reflects spending being registered at Head Offices rather than in the R&D centres where the work is actually carried out. I don’t have an obvious explanation for the relatively low level of spending in the South East and East.

The expectation of a correlation between existing business R&D spend and Innovate UK investments rests on the idea that Innovate UK should be led by the business R&D landscape as it is, rather than trying to shape it. But if the goal of “levelling up” is to increase productivity in underperforming regions, then perhaps the goals of innovation policy should include the use of applied R&D, together with other interventions to promote innovation diffusion and workforce development, explicitly to develop innovation and manufacturing capacity, as Eoin O’Sullivan and I have argued in our recent submission to the Nurse review. As we outline in our paper, this could be done by Innovate UK through the Catapult Network, but this would require some explicit modifications in their mission and in the selection criteria for new Catapults.

One programme run by UKRI in recent years is designed to build regional capacity in this way, through partnership with research organisations and industry in particular places. This is the “Strength in Places Fund”, administered as a partnership between Innovate UK and Research England. I believe this scheme has been a success in the collaborations it has generated, although the bureaucracy surrounding it has been frustrating. It’s very disappointing that the White Paper lacked any commitment to continue this scheme, currently the only explicitly place-based funding instrument run by UKRI. Hopefully this will be remedied in the ongoing detailed discussions of the CSR settlement; if not it will inevitably interpreted as a signal of the UKRI’s lack of commitment to addressing regional R&D imbalances.

R&D for levelling up health inequalities

Turning to non-UKRI funding streams, one that does receive a very substantial uplift is the National Institute of Health Research, the research arm of the Department of Health and Social Care. The White Paper, entirely correctly, draws attention to the shocking disparities in health outcomes across the country, which amount to about a decade of life expectancy between the most and least prosperous parts of the country, and sets as another of the 12 “Levelling Up missions” the goal of narrowing this gap. I believe these health inequalities are not just morally unacceptable in a prosperous country, they are themselves direct contributors to productivity gaps. Further details of how this aspect of levelling up will have to wait until another White Paper, promised for later in the year.

Narrowing these gaps should be a key focus of the National Institute of Health Research – yet of all the research funding agencies, this is the one whose funding is most concentrated, not just in the Greater Southeast, but specifically in London. There is in the White Paper a commitment that NIHR will “bring clinical and applied research to under-served areas and communities in England with major health needs to reduce health disparities”, but the targets are currently vague. This refocusing NIHR on the urgent problem of health inequality needs to go further and faster.

Innovation policy to support levelling up needs to be co-created with cities, regions and nations

But making a material change in the distribution of R&D funding using existing mechanisms will always be a hard and slow process. Tom Forth and I, in our 2020 NESTA paper “The Missing Four Billion”, argued that to make a real difference, it will be necessary to devolve significant funding to nations, cities and regions. To make an impact on productivity, R&D interventions need to work with the grain of the existing regional economic base, and even the best central government departments and agencies, in Whitehall or Swindon, can’t be expected to have the local knowledge and develop the partnerships that would make this work. Ultimately, developing an effective regional innovation strategy is a matter of finding out who is doing the innovating, and helping them do more of it.

On the other hand, the necessary organizational and analytical capacity to make good decisions about innovation don’t always exist or aren’t fully developed in our cities and regions. Our answer to this dilemma was the idea of an “Innovation Deal”, where central government work with cities and regions to develop this capacity, in return for substantial devolution of innovation funding.

The White Paper does take a tentative step in this direction. Three “Innovation Accelerators” have been announced, with £100m of funding over three years going to three pilot areas, Greater Manchester, the West Midlands, and Glasgow City-Region. The idea is that national and local government, together with industry and R&D institutions in those cities, will work together to develop projects to improve the strength of the existing R&D base and maximise its economic impact, to attract new investment from international companies at the technological frontier, and to improve the diffusion of technology into the existing business base.

In Greater Manchester, we’ve been preparing for such a programme. The organisation “Innovation Greater Manchester”, which brings together the private sector, universities and the Mayoral Combined Authority, has been developing a pipeline of rigorously tested investment opportunities aimed at driving productivity across the whole of GM. This needs to support not just the city centre economy, where digital and creative industries are currently thriving, but the economies of GM’s outlying boroughs like Rochdale, Bury and Oldham, which are amongst the most deprived communities of the Northwest. Here, initiatives like the Advanced Machinery and Productivity Institute (supported by the Strength in Places Fund) will help existing innovative manufacturing businesses to develop and grow. Innovation GM will work with central government to develop its “Innovation Accelerator” as an exemplar of locally informed innovation policy.

R&D is an important element of the productivity-enhancing investments that should be at the centre of the levelling-up agenda, and it’s right that the Levelling Up White Paper sets as one of its missions the need to increase the R&D intensity – both public and private – of those parts of the country currently not fulfilling their economic potential. Work does remain to translate some of the high level commitments on R&D spending into changes in the way government departments and agencies spend their R&D budgets.

In addition to this, I believe that co-creation – and ultimately devolution – of innovation programmes with city-regions will be important, to incorporate local knowledge about the existing economy, and ultimately to assign local responsibility for the outcomes. Innovation Accelerators are a good first step to develop the institutional landscape for this to work, and I hope that this initiative can soon be rolled out to include other areas of the UK.

Will the government’s interest in regional economic disparities be sustained for the long-term?

Finally, one of the most telling sections of the Levelling Up White Paper is a history of 100 years of local growth policy, with the comment “spatial policy in the UK has, by contrast, been characterised by endemic policy churn…. By some counts, there were almost 40 different schemes or bodies introduced to boost local or regional growth between 1975 and 2015, roughly one every 12 months.” Surely no-one can argue with the White Paper’s call for policies to be applied consistently at sufficient scale over the medium to long term. Addressing the UK’s fundamental problems of disparities in regional economic performance must surely take a project that will take decades, and it’s realistic that the White Paper defines milestones for 2030.

But what will be the longevity of this White Paper itself? Of course, 2030 is beyond the life of this government – but given the prevailing political instability, some may doubt that the “Levelling Up” agenda will even last the year. It’s odd that a central manifesto commitment of a government elected with an 80 seat majority should be in doubt, but it’s not clear that enthusiasm for the agenda is universally shared across the ruling party. Many influential people and institutions doubt that the reduction of the UK’s regional economic disparities is possible or even desirable. In fact, many people and institutions benefit from the current state of affairs, and there’s a surprisingly large constituency for economic stagnation.

So I wouldn’t be surprised if some people in government and its agencies will be tempted to drag their feet, in the hope that if they wait long enough the entire “levelling up” craze will go away. Naturally, I think this would be wrong in principle – the role of regional economic disparities in the UK’s current economic difficulties, and the resulting societal instability, has become more and more obvious and widely acknowledged. I suspect that such foot-dragging would be politically unwise too.