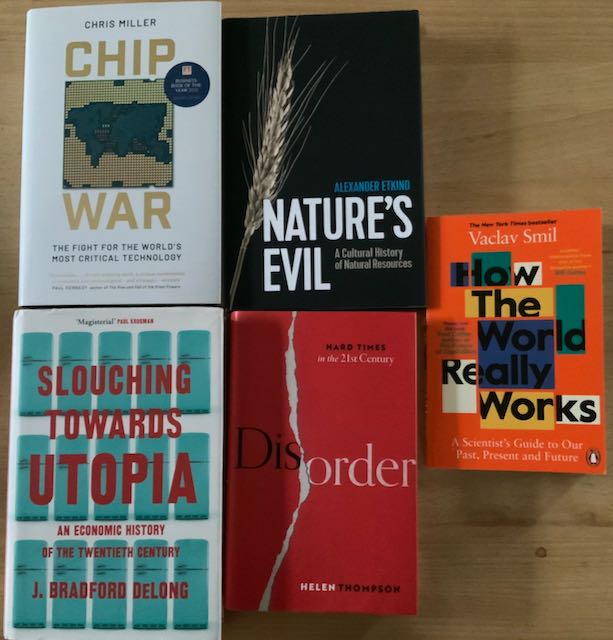

2022 was a thoroughly depressing year; here are some of the books I’ve read that have helped me (I hope) to put last year’s world events in some kind of context.

Helen Thompson could not have been luckier – or, perhaps, more farsighted – in the timing of her book’s release. Disorder: hard times in the 21st century is a survey of the continuing influence of fossil fuel energy on geopolitics, so couldn’t be more timely, given the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on natural gas and oil supplies to Western Europe and beyond. The importance of securing national energy supplies runs through history of the world in the 20th century in both peace and war; we continue to see examples of the deeply grubby political entanglements the need for oil has drawn Western powers into. All this, by the way, provides a strong secondary argument, beyond climate change, for accelerating the transition to low carbon energy sources.

The presence of large reserves of oil in a country isn’t an unmixed blessing – we’re growing more familiar with the idea of a “resource curse”, blighting both the politics and long term economic prospects of countries whose economies depend on exploiting natural resources. Alexander Etkind’s book Natures Evil: a cultural history of natural resources is a deep history of how the materials we rely on shape political economies. It has a Eurasian perspective that is very timely, but less familiar to me, and takes the idea of a resource curse much further back in time, covering furs and peat as well as the more familiar story of oil.

With more attention starting to focus on the world’s other potential geopolitical flashpoint – the Taiwan Straits – Chris Miller’s Chip War: the fight for the world’s most critical technology – is a great explanation of why Taiwan, through the semiconductor company TSMC, came to be so central to the world’s economy. This book – which has rightly won glowing reviews – is a history of the ubiquitous chip – the silicon integrated circuits that make up the memory and microprocessor chips at the heart of computers, mobile phones – and, increasingly, all kinds of other durable goods, including cars. The focus of the book is on business history, but it doesn’t shy away from the crucial technical details – the manufacturing processes and the tools that enable them, notably the development of extreme UV lithography and the rise of the Dutch company ASML. Excellent though the book is, its business focus did make me reflect that (as far as I’m aware) there’s a huge gap in the market for a popular science book explaining how these remarkable technologies all work – and perhaps speculating on what might come next.

Slouching to Utopia: an economic history of the 20th century, by Brad DeLong, is an elegy for a period of unparalleled technological advance and economic growth that seems, in the last decade, to have come to an end. For DeLong, it was the development of the industrial R&D laboratory towards the end of the 19th century that launched a long century, from 1870-2010, of unparalleled growth in material prosperity. The focus is on political economy, rather than the material and technological basis of growth (for the latter, Vaclav Smil’s pair of books Creating the Twentieth Century and Transforming the Twentieth Century are essential). But there is a welcome focus on the material substrate of information and communication technology rather than the more visible world of software (in contrast, for example, to Robert Gordon’s book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, which I reviewed rather critically here).

Though I am very sympathetic to many of the arguments in the book, ultimately it left me somewhat disappointed. Having rightly stressed the importance of industrial R&D as the driver of the technological change, this theme was not really strongly developed, with little discussion of the changing institutional landscape of innovation around the world. I also wish the book had a more rigorous editor – the prose lapses on occasion into self-indulgence and the book would have been better had it been a third shorter.

In contrast, Vaclav Smil’s latest book – How the World Really Works: A Scientist’s Guide to Our Past, Present and Future – clearly had an excellent editor. It’s a very compelling summary of a couple of decades of Smil’s prolific output. It’s not a boast about my own learning to say that I knew pretty much everything in this book before I read it; simply a consequence of having read so many of Smil’s previous, more academic books. The core of Smil’s argument is to stress, through quantification, how much we depend on fossil fuels, for energy, for food (through the Haber-Bosch process), and for the basic materials that underlie our world – ammonia, plastics, concrete and steel. These chapters are great, forceful, data-heavy and succinct, though the chapter on risk is less convincing.

Despite the editor, Smil’s own voice comes through strongly, sceptical, occasionally curmudgeonly, laying out the facts, but prone to occasional outbreaks of scathing judgement (he really dislikes SUVs!). Perhaps he overdoes the pessimism about the speed with which new technology can be introduced, but his message about the scale and the wrenching impact of the transition we need to go through, to move away from our fossil fuel economy, is a vital one.