Regular readers of this blog won’t need reminding that the UK is in a stagnant bind, with economic measures like productivity and GDP per person flatlining since the global financial crisis (or earlier). The consequences are felt well beyond these arid economic aggregates; wage growth has slowed down, successive governments find it hard to fund acceptable public services, and there’s a palpable sour sense of malaise in our politics.

One interesting response to this has been the emergence of a loose constellation of commentators, activists and pressure groups, a techno-optimist movement calling for more houses to be built, for the barriers apparently stopping the country building infrastructure to be swept away, for cheaper and more abundant energy.

Britain Remade wants to “reform the planning process to deliver more clean energy projects, transport infrastructure, and new good quality housing at speed”, while the yimby Alliance , as keen subscribers to the “Housing theory of everything”, focus on the need to build more houses. A very widely talked about paper, Foundations: Why Britain has stagnated focuses on housing, infrastructure, and the cost of energy. Rian Chad Whitton likewise focuses on high energy prices, connecting this with the decline of the UK’s manufacturing base.UKDayOne focus on science, innovation and technology as the motor for UK growth and prosperity, particularly emphasising AI and nuclear power.

I’m going to follow Tom Ough and Calum Drysdale in gathering these strands together under the banner “Anglofuturism”. Their eponymous, and interesting, podcast embraces a cheerful and optimistic version of this vision, with its whimsical AI generated illustrations of flying pubs and thatched space stations.

But I believe the term (in its current manifestation, at least) was coined by the journalist Aris Roussinos, in rather darker hues. This was a call for rebuilt state capacity in a definitively post-liberal world, a vision that owed less to Adam Smith, and more to Thomas Hobbes, which some readers might think more appropriate to deteriorating geopolitical situation we face.

I don’t think there is an entirely consistent underlying political ideology here, but I think it’s fair to say that there’s a common centre of gravity on the centre right. This isn’t the place to analyse political antecedents or implications, and I’m not the right person to do that, but I do want to make some remarks about this emerging movement.

There is much in this agenda that I applaud and agree with. The UK needs to get back to productivity growth, and there is no fundamental reason why that shouldn’t happen. We haven’t reached some final technological barrier – far from it. And I think there’s a profoundly humanistic perspective at work here – people should be able to enjoy the fruits of prosperity.

Of course, there is an opposing argument that believes that continued economic growth is inconsistent with planetary limits. It’s clear that we need to move to a new model of economic growth that doesn’t impose externalities on the global environment, and in particular we need to shift our energy economy to one that doesn’t depend on fossil fuels. But to embrace “degrowth” is in my view both politically infeasible and, if sufficient will and resources are applied, technologically unnecessary. To put it another way, the last 15 years in the UK have been an experiment in degrowth, and the results have been ugly.

There’s an undercurrent of generational justice here too. The perception that young people in the UK can’t look forward to the same lifestyle as their parents is profoundly depressing. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the unaffordability of housing.

Where I think these analyses are less convincing is in identifying the origins of our current problems. In particular, I think an explanation of our current productivity stagnation needs to account for its timing. It’s certainly convincing to argue, as these authors do, that we would be better off if the UK had built more infrastructure over the last few decades, but I don’t think they really convince in talking about what conditions would have produced that outcome. Anglofuturism, in all its varieties, could be accused of willing worthy ends, without really specifying the means.

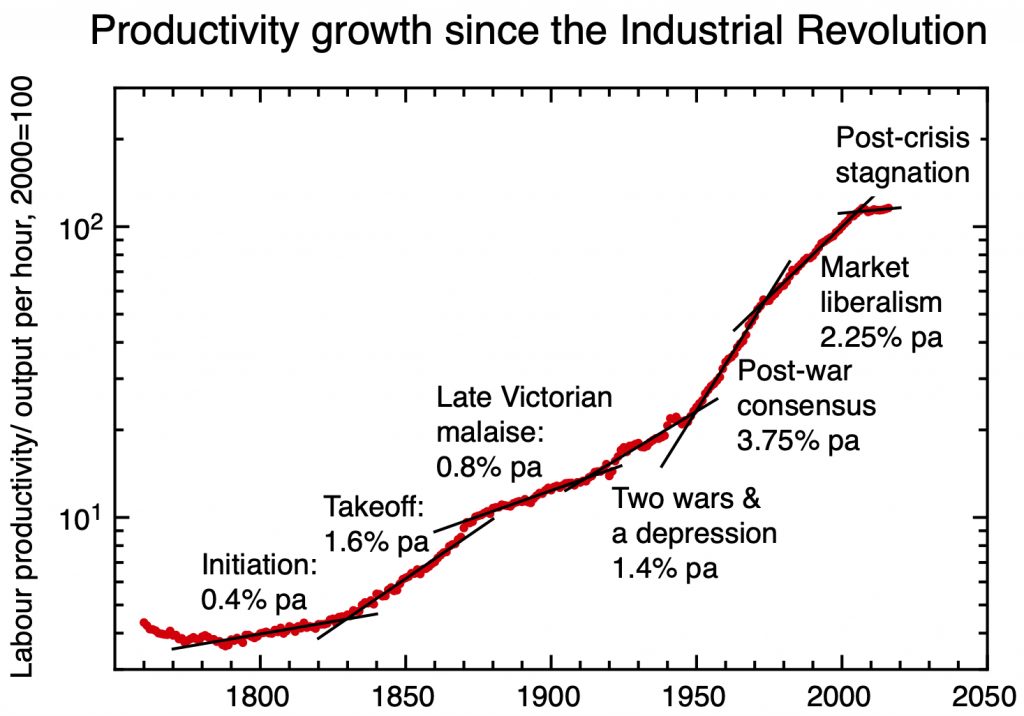

Labour productivity in the UK since the Industrial Revolution. Data from the Bank of England A millennium of macroeconomic data dataset, plot & fits by the author.

The Foundations paper puts a lot of blame on the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act – and the wider Attlee settlement. But I don’t think this makes sense in terms of the timing. As my figure shows, the period of fastest productivity growth in the entire history of the UK took place between 1948 and 1972. In fact, Roussinos harks back to this period, referring to “the optimism and high modernism of the post-war era, a vanished world of frenetic housebuilding and technological innovation where British scientific research could lead the world, and produce higher living standards through its fusion with well-paid, high-skilled labour.”

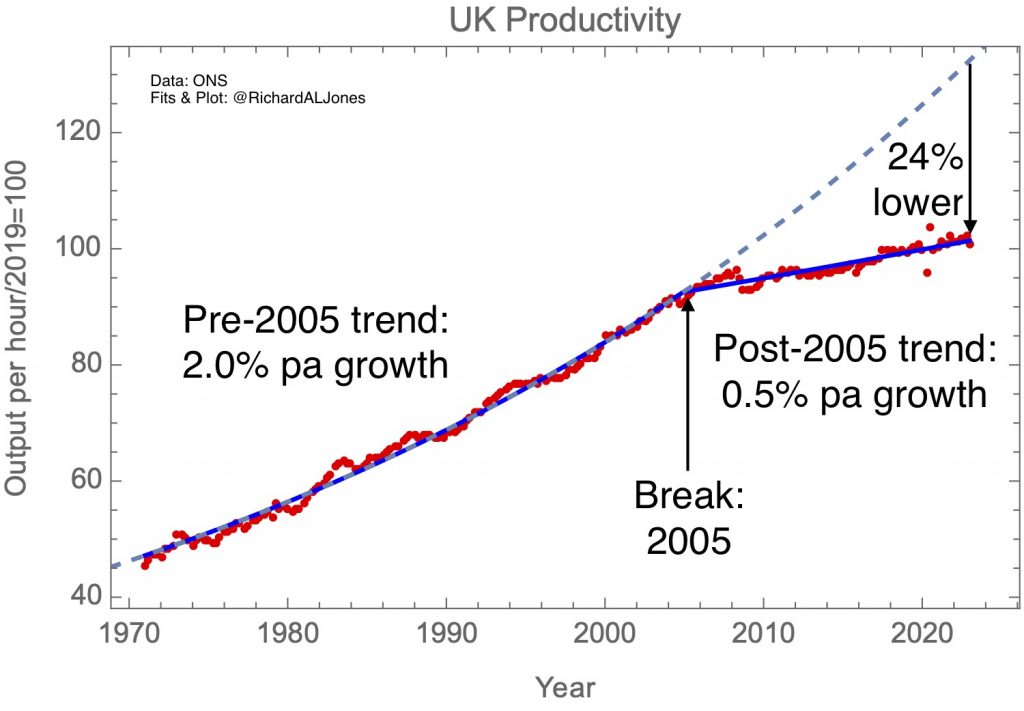

Labour productivity in the UK since 1970. ONS data, fit by the author. For the rationale for putting the break around 2005, see When did the UK’s productivity slowdown begin?

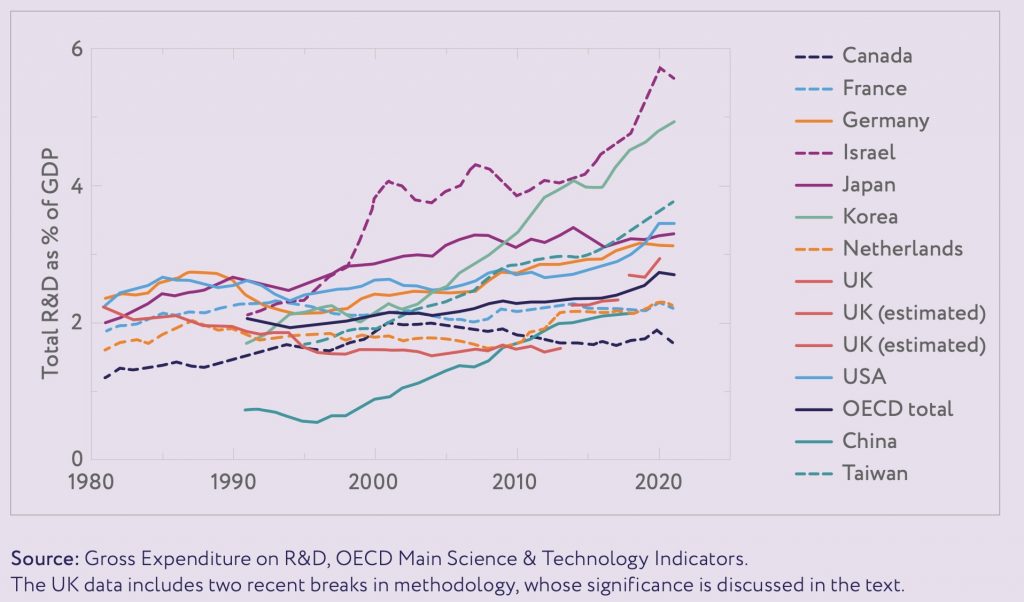

What needs to be explained is that the current slowdown began in the mid-2000s. There is some overlap with a developing consensus view from mainstream economics that the immediate problem has been a lack of investment in the UK economy (see e.g. The Productivity Agenda). This includes public investment in hard infrastructure, private investment in capital goods, and investment in intangibles like R&D. In my own work I’ve emphasised the significant reduction in the R&D intensity of the UK economy between 1980 and 2005, and given the generally technocentric flavour of the Anglofuturists, I’m surprised that this aspect isn’t more prominent in their arguments.

From Research, innovation and the R&D landscape, by R.A.L. Jones, in The Productivity Agenda.

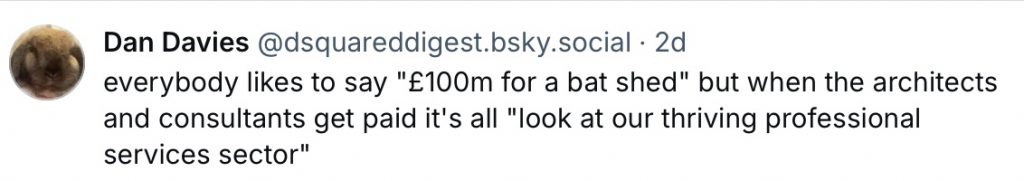

Even if one agrees that investment levels have been too low, there isn’t really a consensus about the ultimate cause of the lack of investment. One common thread is a sense that building infrastructure in the UK has become too expensive because of excessive regulation. In one sense, this is a reflection of the fact that the comparative advantage of the UK is to be found in professional services. One can celebrate that fact that the UK has become a “services superpower”, but the downside was caustically expressed in this comment from Dan Davies

Giles Wilkes has discussed what he terms the “crud economy” at a bit more length. Economic actors respond to incentives, and this doesn’t always direct activity towards where we need it. As Giles puts it: “We need vastly more clean energy, actual hard defence equipment for handling nasty rogue nations, the soldiers to use it, and much more numerous and productive care and health workers for the ageing population. Mitigating the dangerous effects of climate change is going to take real physical capital and effort. These are actual hard problems – and being able to produce more streaming videos, intelligent AI-related chat, or brilliant legal ‘solutions’ to financial market problems is not exchangeable for the assets we need for the real problems. Just because the lawyer’s fee is expressed in dollars, and so is the cost of transforming the US electricity system, doesn’t mean the two can get traded together.”

One thing all branches of Anglofuturism agree on is the need for abundant, cheap energy, and on the bad economic effects that current high industrial energy prices are causing. This clearly causes strong feelings, to judge by the violent on-line reaction to Tom Forth’s entirely reasonable, from a classical market liberal perspective, comments about this, arguing that, while this situation was not good, it was “a smaller problem and of a lower priority than many other restrictions on growth in Britain.”

I agree that it would be better if energy prices in the UK were lower, but I think it is important to understand how this situation has arisen. High industrial energy prices now are causing serious problems for what industry remains in the UK, but I don’t think they can be blamed for the UK’s greater degree of deindustrialisation that its neighbours. This took place at a time when energy prices were low and falling.

The decision the UK government made in the 1980s was that energy was just another commodity whose supply could be left to the market. As it happened, this coincided with a moment in time when the UK switched from being a net importer of energy, to being a net exporter, having found abundant supplies of natural gas and oil in the North Sea. North Sea oil and gas production peaked around 2000, and the country switched to being an energy importer again in 2004. The UK’s relative success in decarbonising its electricity supply initially relied on an early switch from coal to gas; even after the more recent expansion of offshore wind the price of electricity is set by the internationally traded price of gas. This was fine until it wasn’t – in the 2022 gas price spike.

If our problem is that we rely on imported gas, whose fluctuating price is beyond our control, together with offshore wind, which is necessarily intermittent (as well as being generated a long way from where it is needed, connected by an inadequate grid), would it not be better if a much higher proportion of our energy was generated by nuclear fission?

An enthusiasm for nuclear power is a common thread running through all strands of Anglofuturism, and it’s one with which I have much sympathy. For all the progress there’s been in renewable energy, in 2022, 77.8% of our energy still came from oil, gas and coal, and I think it’s going to be difficult to have a fossil-fuel free energy economy which doesn’t depend on some nuclear power to provide firm energy . I deeply regret the failure of the nuclear new build programme of recent governments – of the 18 GW of new generating capacity planned in 2014, only 3.2 GW is even under construction.

But I think it is important, and salutary, to understand why this failure has occurred. My recent blog posts go into the story of the UK’s civil nuclear power programme in some detail . There are ways in which the regulatory and planning framework for civil nuclear could be streamlined, but the fundamental problem with Hinkley C wasn’t the fish disco. It was the fact that the UK government wanted the Chinese state to pay for it, and the French state to build it, as the UK state no longer had the will or capacity to do either.

The UK’s own civil nuclear industry was killed in the 1990s; in an environment of high interest rates and low natural gas prices, and an ideological commitment to leave energy supply to the market, there was no place for it. I do think the UK should recreate its capacity to build nuclear power stations, including the small modular reactors that are currently attracting much attention, but I don’t think this will happen without substantial state intervention.

I agree with the Anglofuturists that we shouldn’t resign ourselves to our current economic failures. I think we need to ask ourselves what has gone wrong with the variety of capitalism that we have, that has led us to this stagnation. It’s a problem that’s not unique to the UK, but which seems to have affected the UK more seriously than most other developed countries. The slowdown seems to have begun in the 2000s, crystallising in full at the Global Financial Crisis.

This timing points to changes in the nature of capitalism and political economy that took hold in the decades after 1980, with the ascendancy of

market liberalism, the doctrine of shareholder value in corporate management, and an enthusiasm for outsourcing government functions to private contractors, no matter how central to the core purposes of the state they might appear to be. In the UK, even the Atom Weapons Establishment has been run by private contractors since 1989, with the government only taking ownership and control back from SERCO in 2020.

We have a new form of globalisation that followed from abolishing capital controls, together with a conviction that one doesn’t need to worry about the balance of payments, even though the persistent trade deficits the UK has run since then has meant ownership and control of national assets has moved overseas. We have a financial system that seems unable to direct resources to those activities that lead to long-term growth. We have a hollowed out state, that now lacks the capacity even to be an informed and effective contractor for services.

I agree with the Anglofuturists that our current stagnation isn’t inevitable, and I applaud their lack of defeatism. It doesn’t have to be this way – but to get beyond our current malaise, I think we need to ask some deeper questions about how our economy is run.