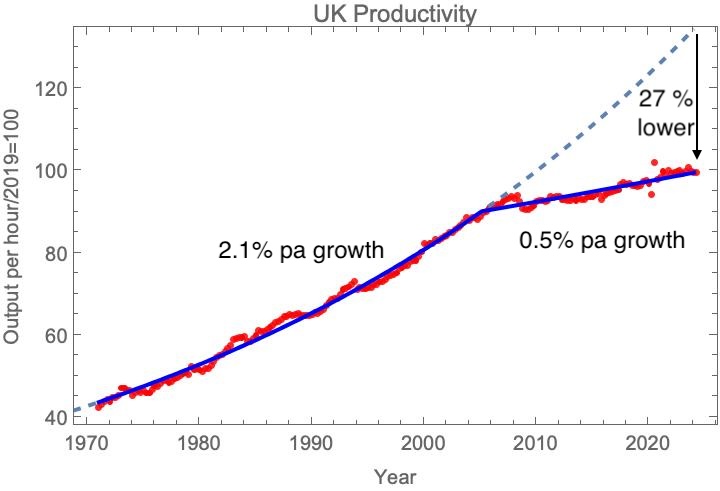

An advantage of having a long-running blog like this one, which is now twenty years old, is that it gives me an easy way of checking out some of the topics that were most exercising me at various points in the past. But it’s still a bit of a shock to realise that it’s been 10 years since I started banging on about the dramatic fall in the UK’s productivity growth rate. My plot emphasises that nothing has happened in the last ten years to change that dismal trend.

UK labour productivity, index 2022=100. Data: ONS, 15/11/2024 release. Line: non-linear least squares fit to two exponential functions, continuous at the break point, which occurs at 2005 for the best fit. See When did the UK’s productivity slowdown begin? for more details of the fitting approach.

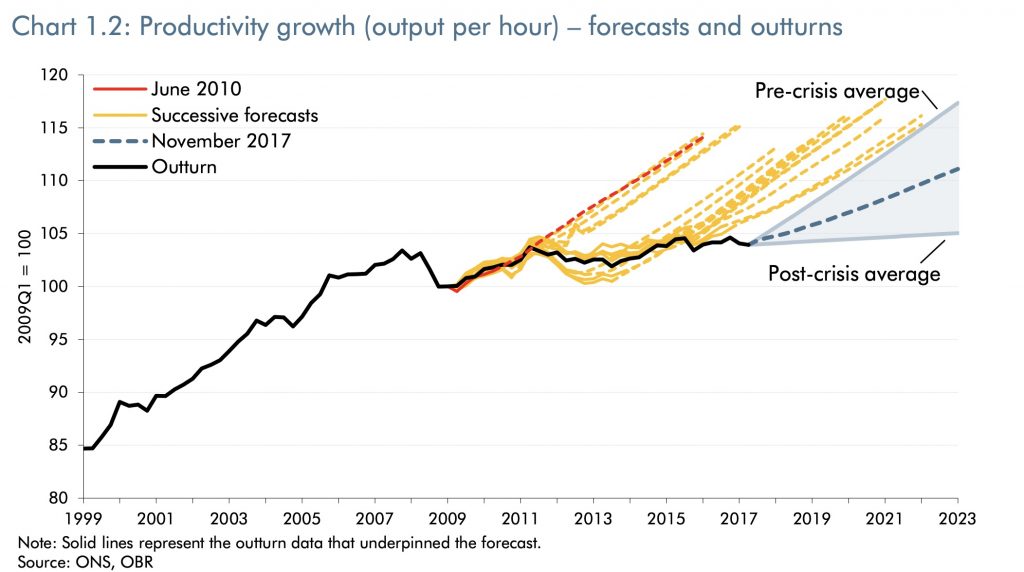

The consensus at the time was that the problem was likely to be self-correcting, and that one could expect a resumption of the earlier trend of productivity growth (if not a recovery of lost ground). Nothing illustrates this better than the successive predictions of the Office of Budgetary Responsibility, which took until 2017 to realise that a new dawn for productivity growth might not be immediately around the corner.

Successive estimates, made between 2010 and 2017 by the Office of Budgetary Responsibility, of future productivity growth, as reported in the November 2017 Economic and Fiscal Outlook

In discussing productivity, my initial focus was on research and development. I’d already drawn attention to the long fall in the UK’s business R&D intensity, and in my June 2014 piece Business R&D is the weak link in the UK’s innovation system I connected this with two of the UK’s problems – its slump in productivity growth, and its persistent current account deficit.

In a follow-up piece, Rebuilding the UK’s innovation economy, I linked low business R&D to the wider problem of short-termism, as identified in the 2012 Kay Review of UK Equity Markets and Long-Term Decision Making, writing that “our shrinking R&D base is part of a bigger problem of short-termism, in which the structures of our capital markets and the reward structures for company managers excessively reward good financial performance in the present at the expense of longer term prospects for growth”.

What did I think ought to be done about it? What I was clear wouldn’t work by itself is what I call “supply side innovation policy” – the idea that if one supports basic science in universities and provides a supply of skilled people, that will automatically lead to economically significant private sector innovation: “But there’s no point driving [university based] scientists to be more collaborative with applied researchers in the private sector, if the private sector doesn’t have the R&D capacity to collaborate with”.

Instead, I argued that we needed to build that capacity, in key areas like health related research and energy: To be clear, here I’m not primarily talking about academic science; what is needed is directed R&D focused on delivering products. For some of these products – for pharmaceutical and medical innovations – the government will be the main customer, as well as being the direct financial beneficiary of savings in areas like the social care budget.

For energy, I argued that the emphasis should be on driving costs down for low carbon energy, including nuclear: “In the case of energy, the costs will be imposed on future customers through long-term guaranteed prices. For example, the Hinckley Point deal, for just one nuclear power station, will result in the transfer of several tens of billions of pounds from domestic and business electricity users to the overseas providers of the technology and finance. Instead of simply standing back and paying these bills (or imposing them on future taxpayers and customers),the government should use its power as the purchaser or guarantor to make sure new technologies are developed for the which the UK can capture significant value.”

To understand the causes of the productivity slowdown more fully, one needs to dive into a more detailed analysis of productivity performance in different sectors. My January 2015 piece,

Growth, technological innovation, and the British productivity crisis, took a first look at this, using early estimates from the ONS for total factor productivity by sector. Here there was a contrast between steady growth in ICT and manufacturing, and peaks – and subsequent falls – in two broad sectors: Agriculture, forestry & fishing, mining & quarrying, utilities, and Financial and Insurance. For the sectors including mining and quarrying, the peak was at 2003, and I believe that this largely reflected the output of the oil and gas sector – production of North Sea oil peaked around 2000. For the sectors including financial services, the peak was at 2007, so unsurprisingly correlated with the onset of the global financial crisis. My conclusion was essentially that the UK had been a victim of what economists call “Dutch disease”, following the peaking of North Sea oil and the bursting of a financial services bubble: “Manufacturing and ICT have been squeezed out by the apparently greater, but ultimately unsustainable, returns from oil and finance, and when those wells dried up the economy was left stranded.”

I still believe that Dutch disease is a helpful, though partial, lens to look at our productivity slowdown through. But since then we’ve learnt a lot more about the proximate causes of the UK’s sluggish productivity growth, and the sectors that have most contributed to the slowdown. A good overview can be found in The Productivity Agenda, from the University of Manchester based Productivity Institute (including a section by me on R&D).

For example, careful econometric analysis has identified that the key contributors to the slowdown, in sectoral terms, have been transport equipment, pharmaceuticals, computer software and telecommunications. This is counterintuitive, in that these sectors are generally thought of as strengths of the UK economy.

More generally, there seems to be a consensus that low levels of investment – in both the public and private sectors – is a major proximate cause of low productivity growth. I would include in this low overall investment record, the low levels of business R&D that first attracted my attention, more than a decade ago. Since it is widely accepted that technological innovation provides the basis for productivity growth, and R&D provides a formal structure for developing and implementing technological innovations, I would still insist on its importance.

But this doesn’t not yet answer the question of what it is about the UK’s political and economic system that has led to this state of chronic underinvestment, or what should be done to address that. The consequences, though, are clear – slow productivity growth has led to stagnating living standards and difficulties in funding public services at the level people expect. For my last words here, I’ll quote what I wrote in July 2014:

“The erosion of the UK’s capacity to technologically innovate was not inevitable – it was the unintended consequence of a series of political and policy choices over decades. We need to reverse this loss of capacity. This needs to be done as part of a broader rethinking of the variety of capitalism the UK economy is currently based on. Without this rethinking, we will be condemned to continue on our current trajectory of low growth, poor trade performance and ultimately, loss of national sovereignty.”