An essay review of Kathleen Taylor’s book “The Fragile Brain: the strange, hopeful science of dementia”, published by OUP.

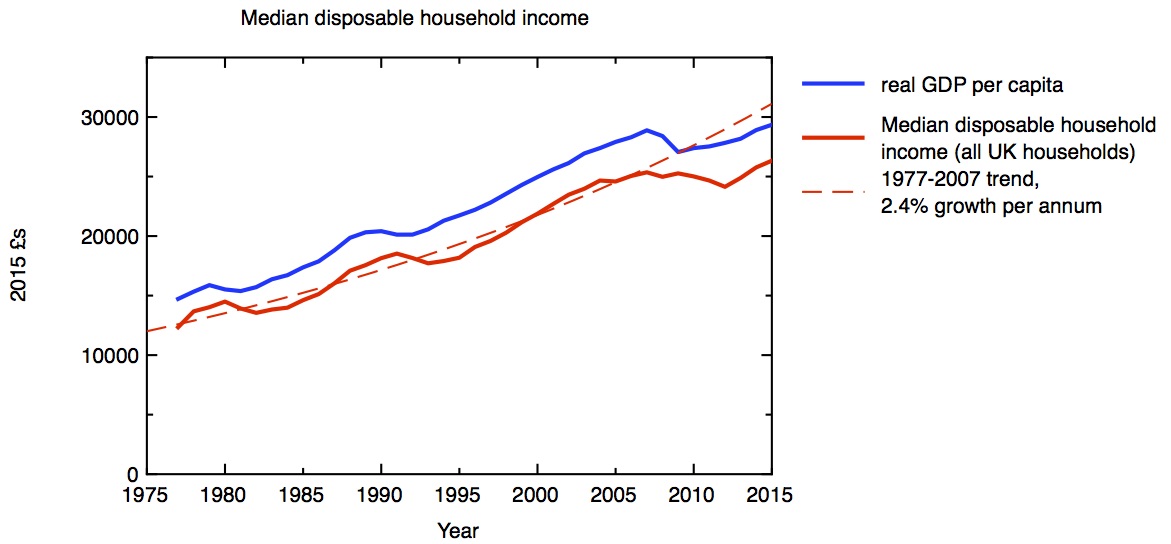

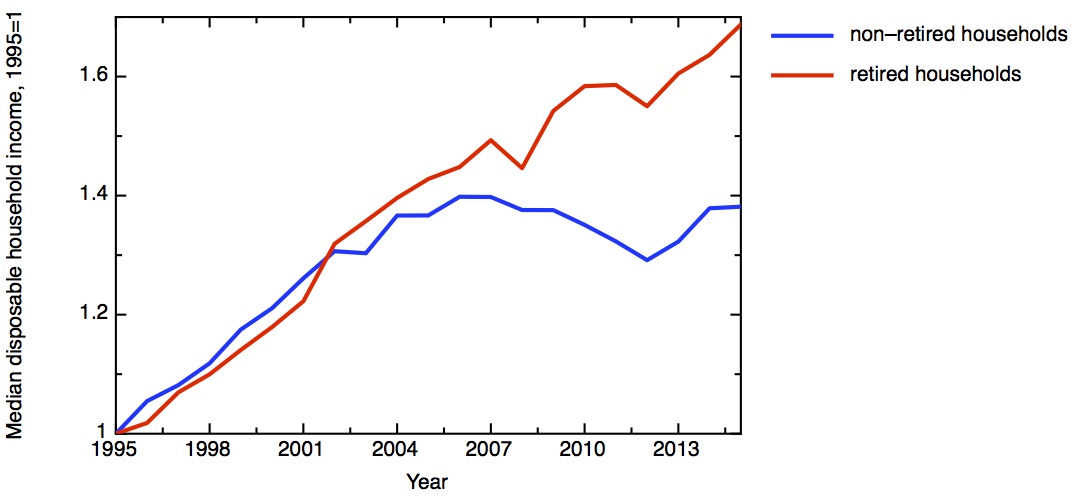

I am 56 years old; the average UK male of that age can expect to live to 82, at current levels of life expectancy. This, to me, seems good news. What’s less good, though, is that if I do reach that age, there’s about a 10% chance that I will be suffering from dementia, if the current prevalence of that disease persists. If I were a woman, at my age I could expect to live to nearly 85; the three extra years come at a cost, though. At 85, the chance of a woman suffering from dementia is around 20%, according to the data in Alzheimers Society Dementia UK report. Of course, for many people of my age, dementia isn’t a focus for their own future anxieties, it’s a pressing everyday reality as they look after their own parents or elderly relatives, if they are among the 850,000 people who currently suffer from dementia. I give thanks that I have been spared this myself, but it doesn’t take much imagination to see how distressing this devastating and incurable condition must be, both for the sufferers, and for their relatives and carers. Dementia is surely one of the most pressing issues of our time, so Kathleen Taylor’s impressive overview of the subject is timely and welcome.

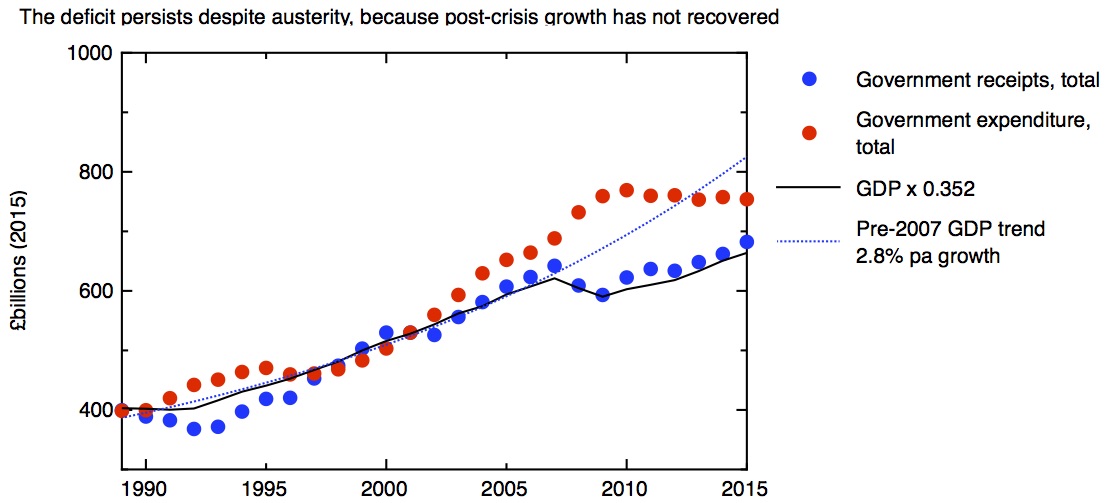

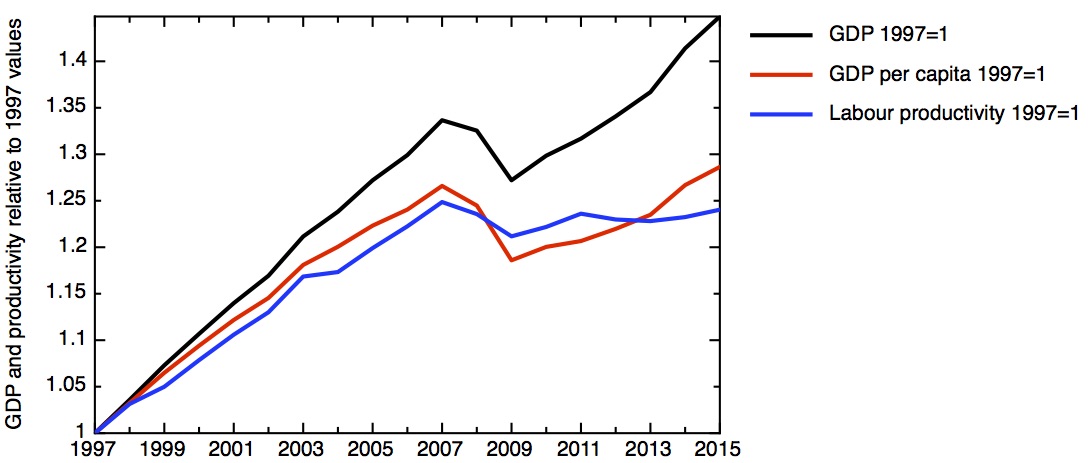

There is currently no cure for the most common forms of dementia – such as Alzheimer’s disease – and in some ways the prospect of a cure seems further away now than it did a decade ago. The number of drugs which have been demonstrated to work to cure or slow down Alzheimer’s disease remains at zero, despite billions of dollars having been spent in research and drug trials, and it’s arguable that we understand less now about the fundamental causes of these diseases, than we thought we did a decade ago. If the prevalence of dementia remains unchanged, by 2051, the number of dementia sufferers in the UK will have increased to 2 million.

This increase is the dark side of the otherwise positive story of improving longevity, because the prevalence of dementia increases roughly exponentially with age. To return to my own prospects as a 56 year old male living in the UK, one can make another estimate of my remaining lifespan, adding the assumption that the increases in longevity we’ve seen recently continue. On the high longevity estimates of the Office of National Statistics, an average 56 year old man could expect to live to 88 – but at that age, there would be a 15% chance of suffering from dementia. For woman, the prediction is even better for longevity – and worse for dementia – with an life expectancy of 91, but a 20% chance of dementia (there is a significantly higher prevalence of dementia for women than men at a given age, as well as systematically higher life expectancy). To look even further into the future, a girl turning 16 today can expect to live to more than 100 in this high longevity scenario – but that brings her chances of suffering dementia towards 50/50.

What hope is there for changing this situation, and finding a cure for these diseases? Dementias are neurodegenerative diseases; as they take hold, nerve cells become dysfunctional and then die off completely. They have different effects, depending on which part of the brain and nervous system is primarily affected. The most common is Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for more than half of dementias in the over 65’s, and begins by affecting the memory, and then progresses to a more general loss of cognitive ability. In Alzheimer’s, it is the parts of the the brain cortex that deal with memory that atrophy, while in frontotemporal dementia it is the frontal lobe and/or the temporal cortex that are affected, resulting in personality changes and loss of language. In motor neurone diseases (of which the most common is ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease), it is the nerves in the brainstem and spinal cord that control the voluntary movement of muscles that are affected, leading to paralysis, breathing difficulties, and loss of speech. The mechanisms underlying the different dementias and other neurodegenerative diseases differ in detail, but they have features in common and the demarcations between them aren’t always well defined.

It’s not easy to get a grip on the science that underlies dementia – it encompasses genetics, cell and structural biology, immunology, epidemiology, and neuroscience in all its dimensions. Taylor’s book gives an outstanding and up-to-date overview of all these aspects. It’s clearly written, but it doesn’t shy away from the complexity of the subject, which makes it not always easy going. The book concentrates on Alzheimer’s disease, taking that story from the eponymous doctor who first identified the disease in 1901.

Dr Alois Alzheimer identified the brain pathology characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease – including the characteristic “amyloid plaques”. These consist of strongly associated, highly insoluble aggregates of protein molecules; subsequent work has identified both the protein involved and the structure it forms. The structure of amyloids – in which protein chains are bound together in sheets by strong hydrogen bonds – can be found in many different proteins, (I discussed this a while ago on this blog, in Death, Life and Amyloids) and when these structures occur in biological systems they are usually associated with disease states. In Alzheimer’s, the particular protein involved is called Aβ; this is a fragment of a larger protein of unknown function called APP (for amyloid precursor protein). Genetic studies have shown that mutations that involve the genes coding for APP and for the enzymes that snip the Aβ off the end of the APP, lead to more production of Aβ, more amyloid formation, and are associated with increased susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. The story seems straightforward, then – more Aβ leads to more amyloid, and the resulting build-up of insoluble crud in the brain leads to Alzheimer’s disease. This is the “amyloid hypothesis”, in its simplest form.

But things are not quite so simple. Although the genetic evidence linking Aβ to Alzheimer’s is strong, there are doubts about the mechanism. It turns out that the link between the presence of amyloid plaques themselves and the disease symptoms isn’t as strong as one might expect, so attention has turned to the possibility that it is the precursors to the full amyloid structure, where a handful of Aβ molecules come together to make smaller units – oligomers – which are the neurotoxic agents. Yet the mechanism by which these oligomers might damage the nerve cells remains uncertain.

Nonetheless, the amyloid hypothesis has driven a huge amount of scientific effort, and it has motivated the development of a number of potential drugs, which aim to interfere in various ways with the processes by which Aβ has formed. These drugs have, so far without exception, failed to work. Between 2002 and 2012 there were 413 trials of drugs for Alzheimer’s; the failure rate was 99.6%. The single successful new drug – memantine – is a cognitive enhancer which can relieve some symptoms of Alzheimer’s, without modifying the cause of the disease. This represents a colossal investment of money – to be measured at least in the tens of billions of dollars – for no return so far.

In November last year, Eli Lilly announced that its anti Alzheimer’s antibody, solanezumab, which was designed to bind to Aβ, failed to show a significant effect in phase 3 trials. After the failure of another phase III trial this February, of Merck’s beta-secretase inhibitor verubecestat, designed to suppress the production of Aβ, the medicinal chemist and long-time commentator on the pharmaceutical industry Derek Lowe wrote: “Beta-secretase inhibitors have failed in the clinic. Gamma-secretase inhibitors have failed in the clinic. Anti-amyloid antibodies have failed in the clinic. Everything has failed in the clinic. You can make excuses and find reasons – wrong patients, wrong compound, wrong pharmacokinetics, wrong dose, but after a while, you wonder if perhaps there might not be something a bit off with our understanding of the disease.”

What is perhaps even more worrying is that the supply of drug candidates currently going through the earlier stages of the processes, phase 1 and phase 2 trials, looks like it is starting to dry up. A 2016 review of the Alzheimer’s drug pipeline concludes that there are simply not enough drugs in phase 1 trials to give hope that new treatments are coming through in enough numbers to survive the massive attrition rate we’ve seen in Alzheimer’s drug candidates (for a drug to get to market by 2025, it would need to be in phase 1 trials now). One has to worry that we’re running out of ideas.

One way we can get a handle on the disease is to step back from the molecular mechanisms, and look again at the epidemiology. It’s clear that there are some well-defined risk factors for Alzheimer’s, which point towards some of the other things that might be going on, and suggest practical steps by which we can reduce the risks of dementia. One of these risk factors is type 2 diabetes, which according to data quoted by Taylor, increases the risk of dementia by 47%. Another is the presence of heart and vascular disease. The exact mechanisms at work here are uncertain, but on general principles these risk factors are not surprising. The human brain is a colossally energy-intensive organ, and anything that compromises the delivery of glucose and oxygen to its cells will place them under stress.

One other risk factor that Taylor does not discuss much is air pollution. There is growing evidence (summarised, for example, in a recent article in Science magazine) that poor air quality – especially the sub-micron particles produced in the exhausts of diesel engines – is implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. It’s been known for a while that environmental nanoparticles such as the ultra-fine particulates formed in combustion can lead to oxidative stress, inflammation and thus cardiovascular disease (I wrote about this here more than ten years ago – Ken Donaldson on nanoparticle toxicology). The relationship between pollution and cardiovascular disease would by itself indicate an indirect link to dementia, but there is in addition the possibility of a more direct link, if, as seems possible, some of these ultra fine particles can enter the brain directly.

There’s a fairly clear prescription, then, for individuals who wish to lower their risk of suffering from dementia in later life. They should eat well, keep their bodies and minds well exercised, and as much as possible breathe clean air. Since these are all beneficial for health in many other ways, it’s advice that’s worth taking, even if the links with dementia turn out to be less robust than they seem now.

But I think we should be cautious about putting the emphasis entirely on individuals taking responsibility for these actions to improve their own lifestyles. Public health measures and sensible regulation has a huge role to play, and are likely to be very cost-effective ways of reducing what otherwise will be a very expensive burden of disease. It’s not easy to eat well, especially if you’re poor; the food industry needs to take more responsibility for the products it sells. And urban pollution can be controlled by the kind of regulation that leads to innovation – I’m increasingly convinced that the driving force for accelerating the uptake of electric vehicles is going to be pressure from cities like London and Paris, Los Angeles and Beijing, as the health and economic costs of poor air quality become harder and harder to ignore.

Public health interventions and lifestyle improvements do hold out the hope of lowering the projected numbers of dementia sufferers from that figure of 2 million by 2051. But, for those who are diagnosed with dementia, we have to hope for the discovery of a breakthrough in treatment, a drug that does successfully slow or stop the progression of the disease. What needs to be done to bring that breakthrough closer?

Firstly, we should stop overstating the progress we’re making now, and stop hyping “breakthroughs” that really are nothing of the sort. The UK’s newspapers seem to be particularly guilty of doing this. Take, for example, this report from the Daily Telegraph, headlined “Breakthrough as scientists create first drug to halt Alzheimer’s disease”. Contrast that with the reporting in the New York Times of the very same result – “Alzheimer’s Drug LMTX Falters in Final Stage of Trials”. Newspapers shouldn’t be in the business of peddling false hope.

Another type of misguided optimism comes from Silicon Valley’s conviction that all is required to conquer death is a robust engineering “can-do” attitude. “Aubrey de Grey likes to compare the body to a car: a mechanic can fix an engine without necessarily understanding the physics of combustion”, a recent article on Silicon Valley’s quest to live for ever comments about the founder of the Valley’s SENS Foundation (the acronym is for Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence). Removing intercellular junk – amyloids – is point 6 in the SENS Foundation’s 7 point plan for eternal life.

But the lesson of several hundred failed drug trials is that we do need to understand the science of dementia more before we can be confident of treating it. “More research is needed” is about the lamest and most predictable thing a scientist can ever say, but in this case it is all too true. Where should our priorities lie?

It seems to me that hubristic mega-projects to simulate the human brain aren’t going to help at all here – they consider the brain at too high a level of abstraction to help disentangle the complex combination of molecular events that is disabling and killing nerve cells. We need to take into account the full complexity of the biological environments that nerve cells live in, surrounded and supported by glial cells like astrocytes, whose importance may have been underrated in the past. The new genomic approaches have already yielded powerful insights, and techniques for imaging the brain in living patients – magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography – are improving all the time. We should certainly sustain the hope that new science will unlock new treatments for these terrible diseases, but we need to do the hard and expensive work to develop that science.

In my own university, the Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience focuses on motor neurone disease/ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases, under the leadership of an outstanding clinician scientist, Professor Dame Pam Shaw. The University, together with Sheffield’s hospital, is currently raising money for a combined MRI/PET scanner to support this and other medical research work. I’m taking part in one fundraising event in a couple of months with many other university staff – attempting to walk 50 miles in less than 24 hours. You can support me in this through this JustGiving page.