As the pandemic moves to a new phase, it’s natural to assume that the Prime Minister would want to make progress on the other agendas that he might hope would define his tenure. Prominent in these has been his emphasis on the need to restore the UK’s place as a “Science Superpower” – for example, in his 15 July speech he said: “We are turning this country into a science superpower, doubling public investment in R and D to £22 billion and we want to use that lead to trigger more private sector investment and to level up across the country”, a theme he’d set out in detail in a 21 June article in the Daily Telegraph. The theme of boosting science and innovation is also crucial to the government’s other key priorities, “levelling up” by reducing the gross geographical disparities in economic performance and health outcomes across the UK, delivering on the 2050 “Net Zero” target, and securing a strategic advantage in defence and security through science and technology in an increasingly uncertain world.

And yet, the public finances are in disarray following the huge increase in borrowing needed to get through the pandemic, the economy has suffered serious and lasting damage, and the talk is of a very tight spending settlement in the upcoming comprehensive spending review, given the need for further spending in the NHS and education systems to start to repair ongoing costs and the lasting aftermath of the pandemic. How robust will the Prime Minister’s commitment to science and innovation be in the face of many other pressing demands on public spending, and a Treasury seeking to bring the public finances back towards more normal levels of borrowing? The government is committed to two R&D numbers – a long term target, of increasing the total R&D intensity – public and private – of the UK economy to 2.4% by 2027. Another shorter term promise – of increasing government spending on research and development to £22 billion by 2024 – was introduced in the 2020 budget, and has recently been reasserted by the Prime Minister – though without a date attached.

Some people might worry that the government could seek to resolve this tension by creative accounting, finding a way to argue that the letter of the commitments has been met, while failing to fulfil their spirit. It would be possible to bend the figures to do this, but this would be a bad idea that would put in jeopardy the government’s larger stated intentions. In particular, anything that involves a reclassification of existing expenditure rather than an overall increase, will do nothing to help the overall goal of making the UK’s economy more R&D intensive, and achieving the overall 2.4% R&D intensity target.

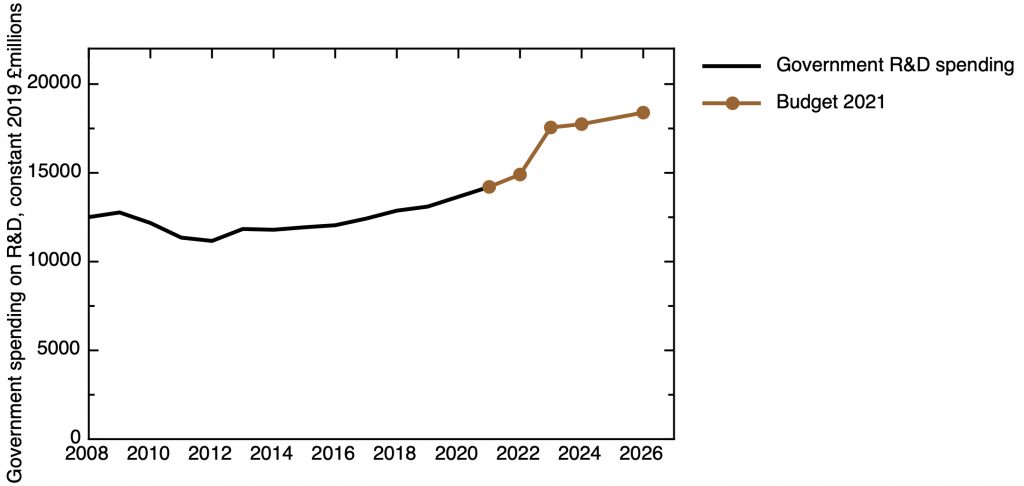

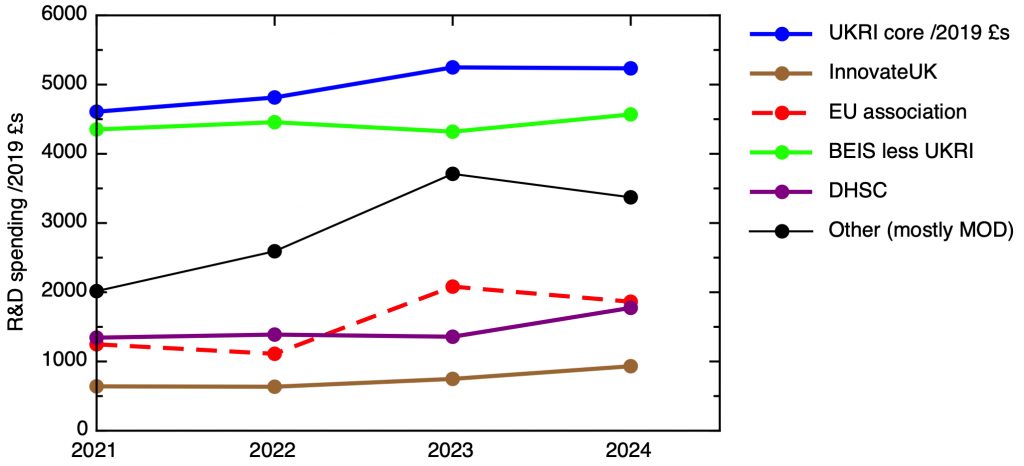

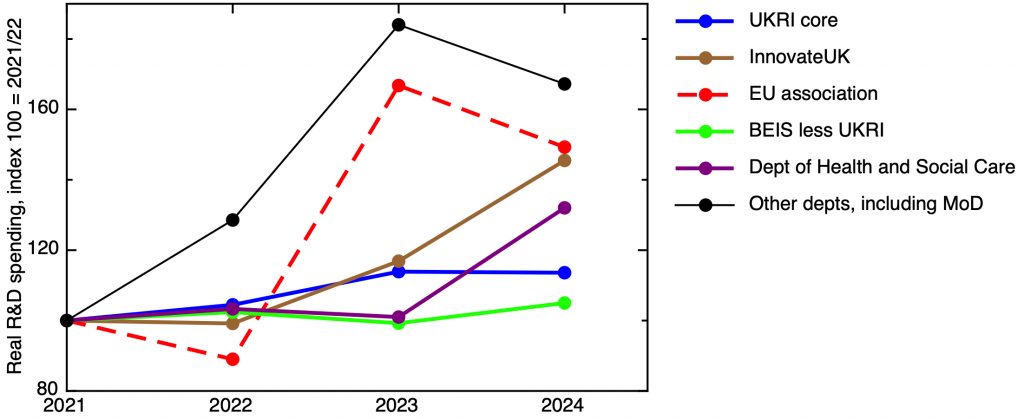

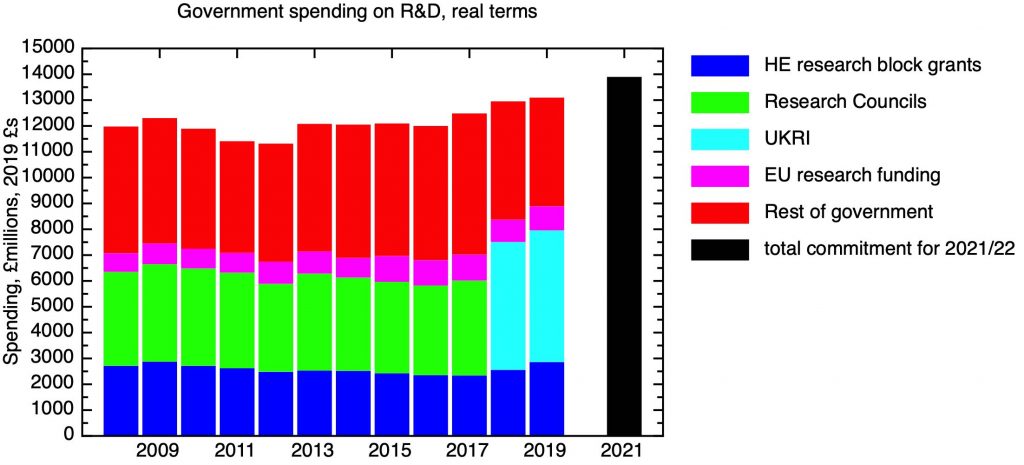

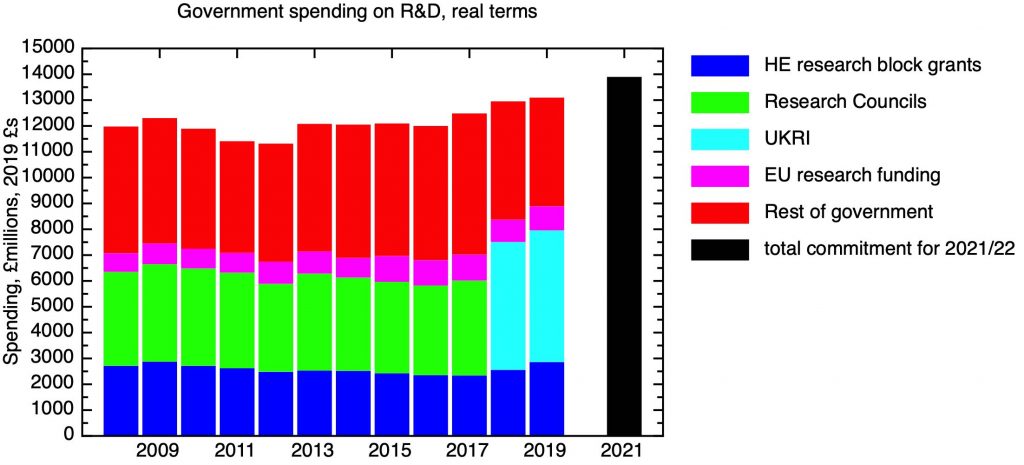

To begin with, let’s look at the current situation. A breakdown of government spending in real terms shows that we have seen real increases, although it will not have felt that way to university-based scientists depending on research council and block grant funding. The increase the plot shows on the introduction of UKRI partly reflects an accounting artefact, by which spending in InnovateUK has been shifted out of the BEIS department budget into UKRI, but in addition to this there was a genuine uplift through programmes such as the “Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund”. These figures also include a notional sum for the UK’s contribution to the EU research programmes. In the future, assuming the question of the UK’s association with the Horizon programme is finally resolved satisfactorily, contributions to the EU research programmes will continue to be included in total R&D investment, as they should be, in my opinion. The uplift we’ve seen in the current year includes a contribution for EU programmes, as well as some substantial increases in R&D funding by government departments, especially the Ministry of Defence (overall departmental spending outside UKRI is dominated by the MoD and the Department of Health and Social Care).

Total government spending on R&D from 2008 to 2019 as recorded by ONS, in real terms. 2021 is announced commitment. UKRI figure excludes Research England, but includes InnovateUK funding, previously recorded as department spending in BEIS (here included in “rest of government”). Research England is included in “HE research block grants”, which also includes university research funding from Devolved Administrations and, pre-2018, HEFCE. Data: Research and development expenditure by the UK government: 2019. ONS April 2021

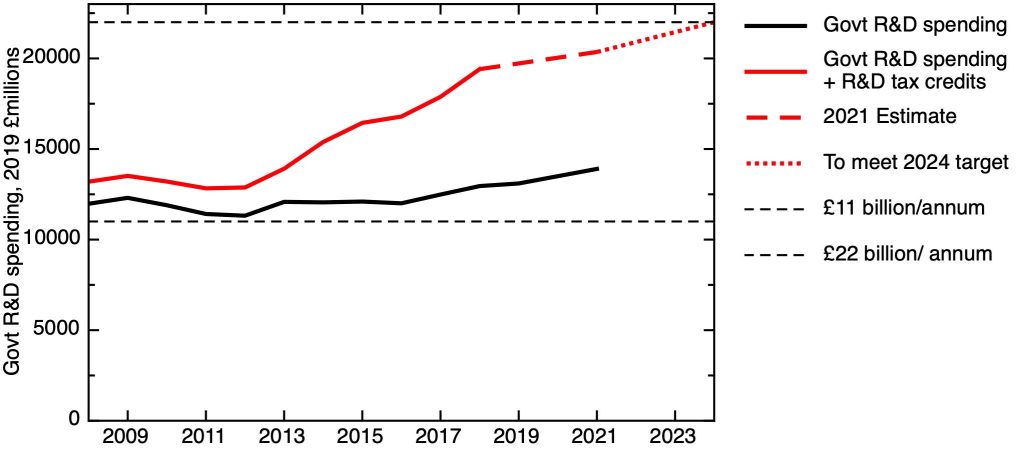

To summarise, it is true to say that government spending is higher now in real terms than it has been for more than a decade. But this still doesn’t look like a trajectory heading towards a doubling, and £22 billion looks a long way away.

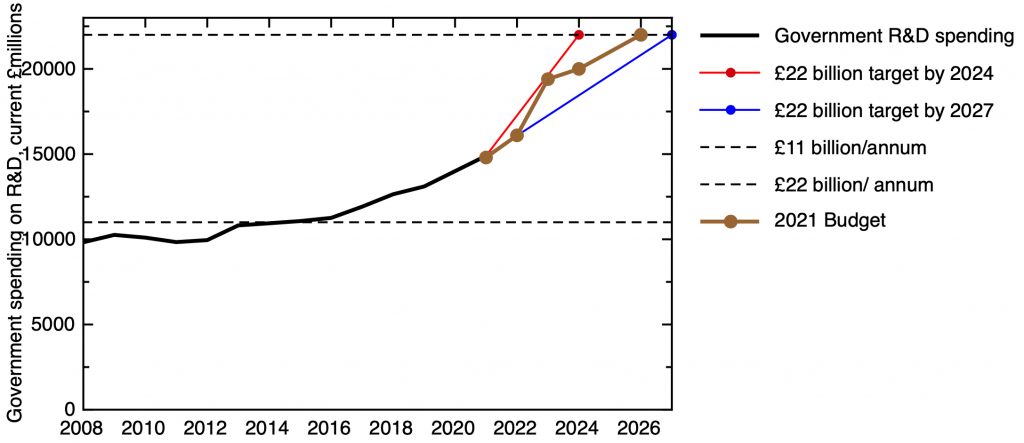

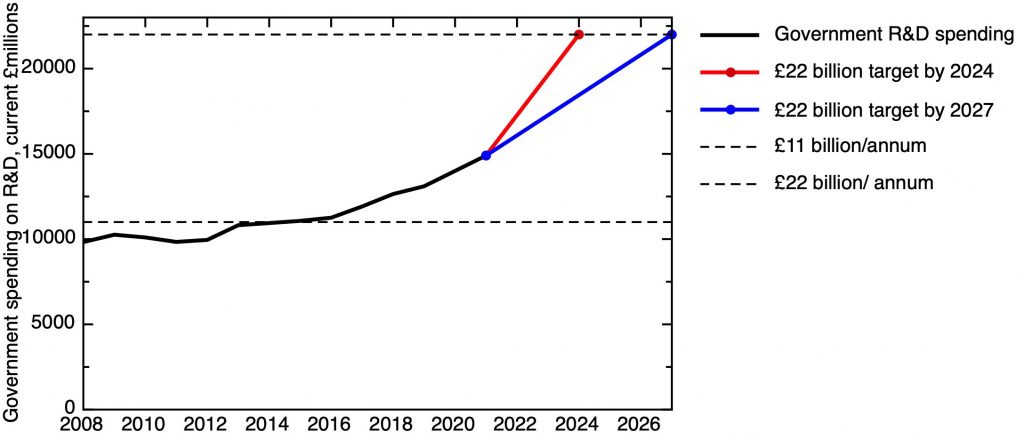

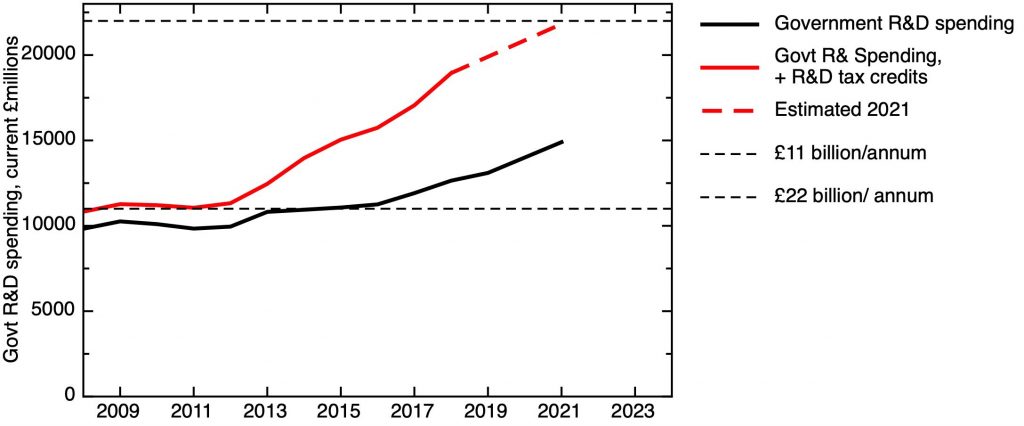

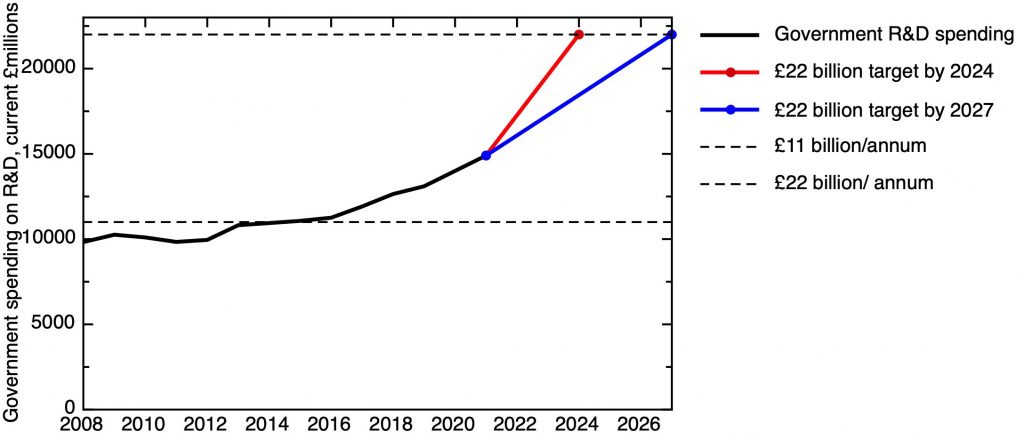

Of course, these are figures that are corrected for inflation; we will see a more flattering picture if we neglect this. And there might be some flexibility over the timescale for achieving the £22 billion target. My next plot shows the overall trajectory of government spending on R&D, in current money, without an inflation correction. The red line indicates the path required to achieve the £22 billion by the original date, 2024. This would require a substantial increase in the rate of the growth we have seen in recent years. But one might argue that the pandemic has forced a slippage of the timescale, which might be aligned with the 2027 target for achieving the overall 2.4% of GDP R&D intensity target. This does look achievable with current rate of nominal growth – and of course the pulse of inflation we’re likely to see now will make achieving £22 billion even easier (albeit at the cost of less real research output).

Total government spending on R&D from 2008 to 2019 as recorded by ONS, in current money (non-inflation corrected) terms. 2021 is announced commitment. Data: Research and development expenditure by the UK government: 2019. ONS April 2021

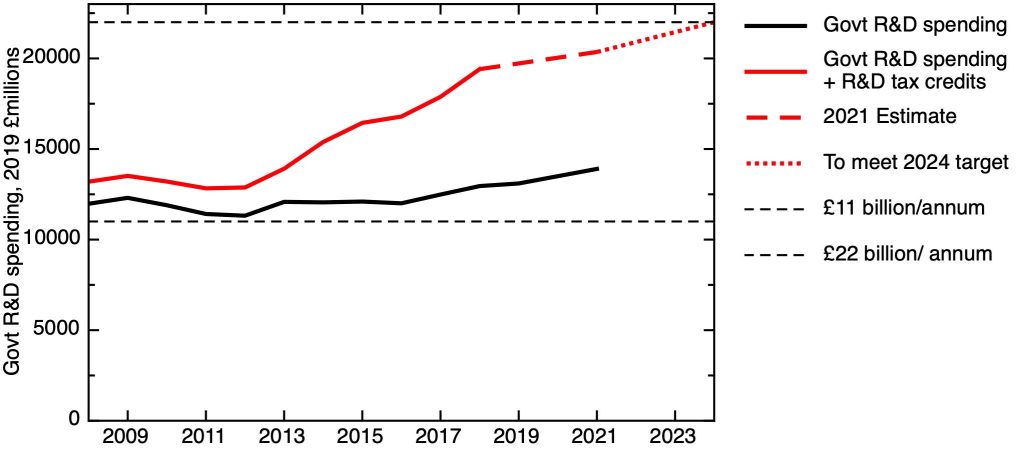

But there is another possibility for modifying the figures that may well have occurred to someone on Horse Guards Road. That would be to include the cost of R&D tax credits. These are subsidies offered by the government for research carried out in business, that according to circumstances can be taken as a reduction in corporation tax liability or a direct cash payment from government (the latter being particularly important for early stage start-ups that aren’t yet generating a profit). This, then, is another cost incurred by the government related to R&D, representing not direct R&D spending, but lost tax income and outgoings. It’s perhaps not widely enough appreciated how much more generous this scheme has become over the last decade, and there is a separate discussion to be had about how effective these schemes are, and the value for money of this very substantial cost to government.

My next plot shows the effect of adding on the cost of R&D tax credits to direct government spending on R&D. The effect is really substantial – and would seem to put the £22 billion target within reach without the government having to spend any more money on R and D.

Government spending on R&D from 2008 to 2019, as above, together with the cost of R&D tax credits (includes an HMRC estimate for total cost in 2019). The estimate for 2021 combines the committed figure for government R&D with the assumption that the cost of R&D tax credit remains the same in real terms as its 2019 value. All values corrected for inflation and expressed in 2019 £s. Uncorrected for the mismatch between fiscal years, by which R&D tax credit data is collected, and calendar years, for R&D spending.

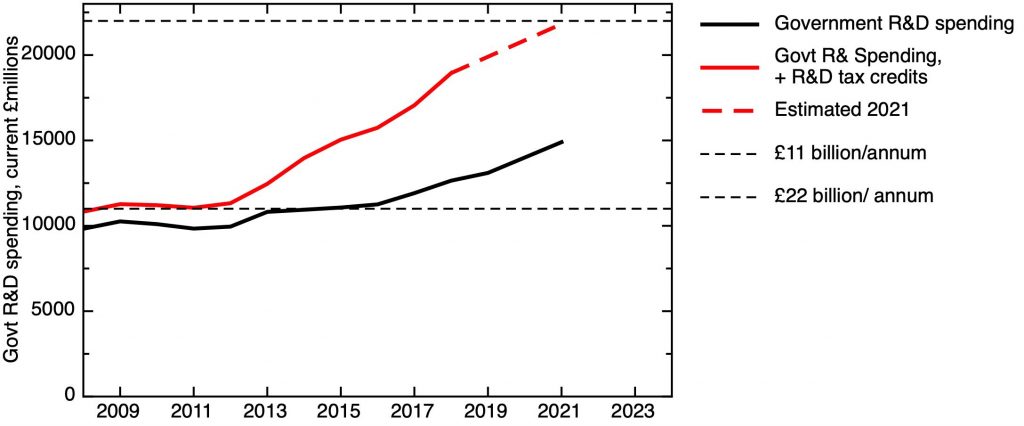

We can make the situation look even better by not accounting for inflation. This is illustrated in the next figure.

Government spending on R&D from 2008 to 2019, as above, together with the cost of R&D tax credits (includes an HMRC estimate for total cost in 2019). The estimate for 2021 combines the committed figure for government R&D with the assumption that the cost of R&D tax credit remains the same in real terms as its 2019 value. All values in nominal current cash terms (uncorrected for inflation). Uncorrected for the mismatch between fiscal years, by which R&D tax credit data is collected, and calendar years for R&D spending.

This not only gets us very close to £22 billion spending ahead of target, but also might allow one to argue that the Prime Minister’s claim of doubling government investment in R&D had been fulfilled, taking the timescale to be a decade of Conservative-led governments.

What would be wrong with this? It would actually lock in a real terms erosion of spending on R&D, and would not help deliver the more enduring target, of raising the R&D intensity of the UK economy to 2.4% of GDP by 2027, most recently reasserted in the HM Treasury document “Build back better: Our Plan for Growth”. This target is for combined business and public sector funding – but redefining government R&D spending to include the government’s subsidy of R&D in business simply moves spending from one heading to another, without increasing its total. This would stretch to breaking to breaking point the larger claim, that the government is “turning this country into a science superpower”.

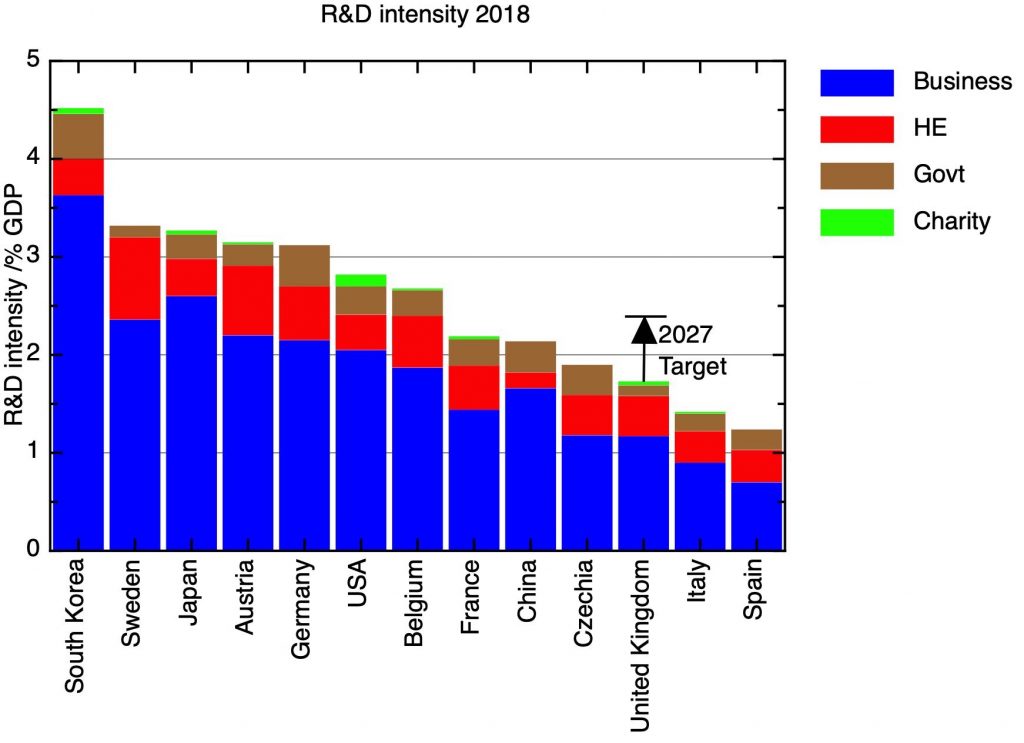

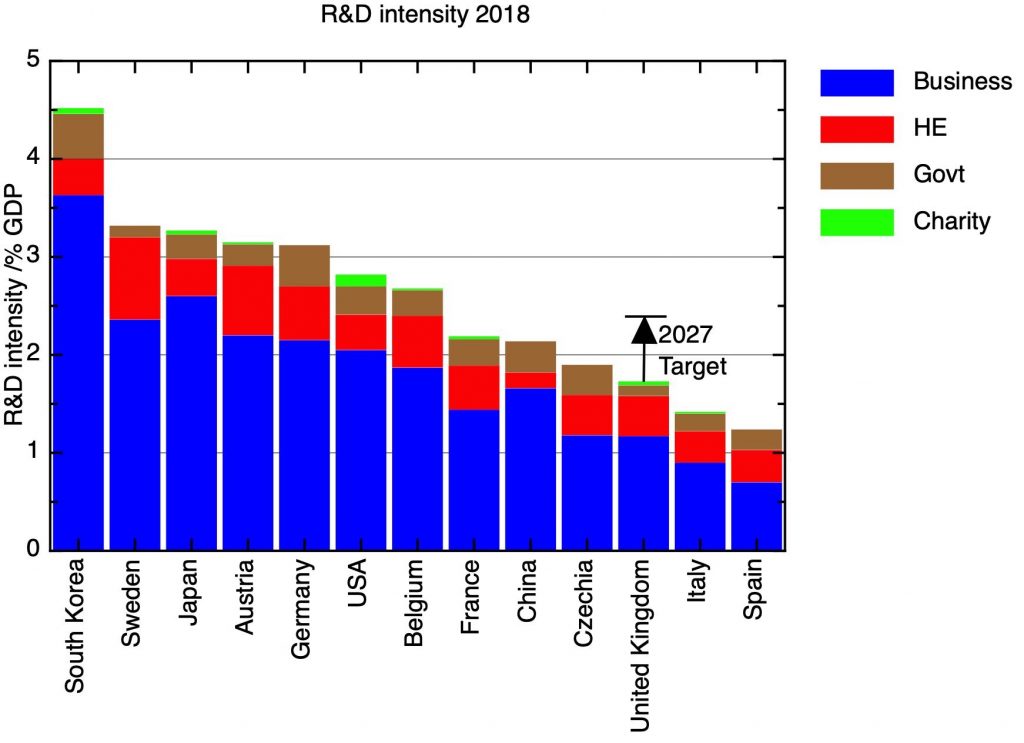

Currently, while the UK’s science base has many strengths, it is too small for an economy of the size of the UK. If we measure the R&D intensity of the economy in terms of total investment – public and private – as a proportion of GDP, the UK is a long way behind the leaders, as my next plot shows. By R&D intensity, the UK is not a leader, or even an average performer, but in the third rank, between Italy and Czechia. The UK’s science base is a potential source of economic and strategic advantage, but it is currently too small.

R&D intensity of selected nations by sector of performance, 2018. Data: Eurostat.

This is widely recognised by policy makers, and is the logic behind the 2.4% R&D intensity target that was in the Conservative manifesto, and has since been frequently reasserted, for example in the Treasury’s “Plan for Growth”. In one sense, this is still not a very demanding target – assuming (unrealistically) that the R&D intensity of other countries remains the same, far from elevating the UK to be one of the leaders, it would leave it just behind Belgium.

How much would the UK’s R&D spending need to increase to meet the 2.4% R&D intensity target? This, of course, depends on what happens to the denominator – GDP – in the meantime. Based on the OBR’s March estimates, we might expect GDP in 2027 to be around £2.4 trillion, up from £2.22 trillion in 2019, before the effects of the pandemic (both in 2019 £s). So to meet the target, total R&D spending – public and private – would need to be £58 billion.

This compares to total R&D spending in 2019 of £38.5 billion, split almost exactly 1/3:2/3 between the public and private sectors (this figure includes expenditure associated with the R&D tax credits, but this appears here on the private sector side). So to achieve the 2.4% target, there needs to be a 50% real terms increase in both public and private sector R&D relative to 2019. If the same split between public and private is maintained, we’d need £19.4 billion public and £38.8 billion business R&D.

There are two points to make about this. Firstly, we note that the estimate for the required public R&D is actually lower than the £22 billion government promise. This reflects the fact that the 2.4% target is less demanding than it used to be, since we now think we’ll be poorer in 2027 than we expected in 2019. However, remember that this is a figure in 2019 £s – so in real terms inflation will push up the nominal value. In fact, a very rough estimate based on the OBR’s inflation projections suggest that £22 billion nominal by 2027 as the government’s investment in R&D could be about right. On the other hand, OBR’s March 2021 forecast was quite pessimistic compared to other forecasters. If GDP turns out to recover more fully from the pandemic than the OBR thought, then R&D spending will need to be higher to meet the target – but this will be easier to fund given a larger economy.

Secondly, note that this split between public and private sector is based on where the research is carried out, not who funds it. So the subsidy provided by the government in the form of R&D tax credits appears on the private sector side of the ledger. Unless the split between public and private dramatically changes over the next few years, then the £22 billion the government needs to put in can’t include the cost of R&D tax credits.

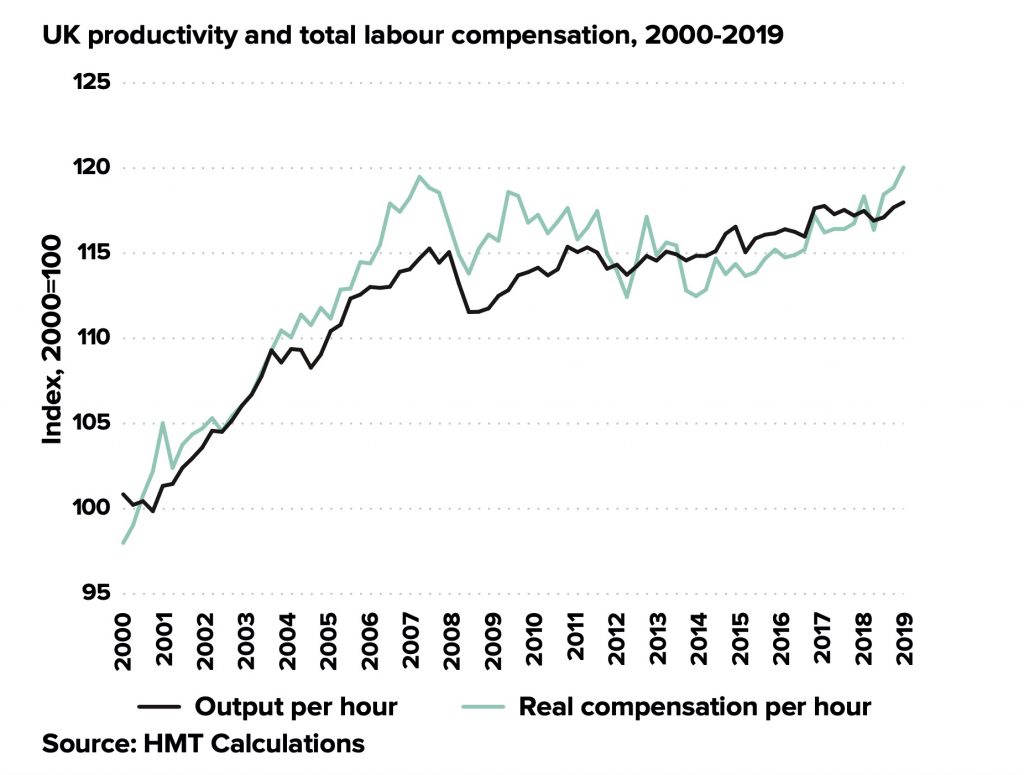

Targets are important, but they are a means to an end. The Plan for Growth identifies “Innovation” as one of three pillars of growth. A return to economic growth, after a decade of stagnation of productivity growth and living standards, capped by a devastating pandemic, is crucial in itself. But innovation also directly underpins the government’s three main priorities.

The first of these is the transition to net zero. This requires a wrenching change of the whole material base of our economy; it needs innovation to drive costs down – and to make sure that it is the UK’s economy and the UK’s communities that benefit from the new economic opportunities that this transition will bring.

The second is “levelling up”, which, to be more than a slogan, should involve a sustained attempt to increase the productivity of the UK’s lagging cities and regions through increasing innovation and skills. This won’t be possible without correcting the imbalance in government R&D investment between the prosperous Greater Southeast and the lagging rest of the country. We shouldn’t put at risk the outstanding innovation economies we do have in places like Cambridge, so this needs to involve new money at a scale that will make a material difference.

Finally, we need to rethink the UK’s position in the world. Part of this is about making sure the UK remains an attractive destination for inward investment by companies at the global technological frontier, and that the UK’s industries can produce internationally competitive products and services for export. But the world has also got more dangerous, and the modernisation of the UK’s armed forces and security agencies needs to be underpinned by R&D.

The government will not be able to achieve these goals without a real increase in R&D spending. That does not mean, however, that we should just do more of the same. We need more emphasis on the “development” half of R&D, we need to coordinate the strategic research goals of the government better across different departments, we need to support the development of internationally competitive R&D clusters outside the southeast, all the while sustaining and growing our outstanding discovery science.

So, could the government game its £22 billion R&D promise, by reclassifying the cost of the R&D tax credit as government investment in R&D and ignoring the effect of inflation? Yes, it could.

Should it? No, it should not. To do so would put the 2.4% R&D intensity target out of reach. It would seriously undercut the government’s main priorities – net zero, “levelling up” – and keeping the UK secure in a dangerous world. And it would put paid to any pretensions the UK might have of recovering “science superpower” status.

Instead, I believe there needs to be realism and honesty – both about the difficulty of the post-pandemic fiscal situation, and the need for genuine increases in government spending in R&D if its long term economic and climate goals are to be met. £22 billion is about the right figure to aim for, but if the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic make it difficult to achieve this on the original timescale, the government should set out a new timescale, with a fully developed timetable outlining how this increase will be achieved in order to deliver the 2027 2.4% R&D intensity target. Early increases should focus on the areas of highest priority – with, perhaps, highest priority of all being given to net zero. Climate change will not wait.